Yazdegerd III (r. 632-651) was the last monarch of the Sassanian Empire (224-651), ruling – or attempting to rule – amidst the chaos of its final decline and fall to the invading Muslim Arabs. He was the son of the prince Shahriyar (d. 628) and grandson of Kosrau II (r. 590-628).

He was also the king whose wars with the Byzantine Empire so severely weakened the Sassanians that they had little strength left to resist the Arab invasion.

Kosrau II's wars, and final defeat, had also divided the nobility – a situation worsened by his successor Kavad II (r. 628) who assassinated all of his brothers and any other would-be claimants to the throne. Young Yazdegerd III was hidden away for his own safety during the civil wars which erupted after Kosrau II's death, only emerging to be crowned when he was around eight years old.

His reign is defined by the disintegration of Sassanian power in the aftermath of the Byzantine Wars, the plague of 627-628, and the onslaught of the Arab Invasion. He was a mere figurehead in the early years of his reign, steered by powerful nobles, and spent the latter part fleeing from one area to another in his tottering empire while the Arabs steadily advanced. He was finally assassinated in the city of Marw as Arab forces were closing on the city. Although members of his family survived the Arab conquest in exile, his death marked the end of the Sassanian Empire and their later efforts could do nothing to change that.

Kosrau II's Wars

The last great king of the Sassanians was Kosrau I (r. 531-579) who brought the empire to its height. His son, Hormizd IV (r. 579-590), continued his policies and maintained the stability of the empire but was challenged by a popular general named Bahram Chobin (d. c. 591) who was backed by powerful nobles and his loyal troops. The conflict between Hormizd IV and Bahram Chobin destabilized the empire and, in an effort to restore order, Hormizd IV was assassinated either by his brothers or his son Kosrau II, who then took the throne.

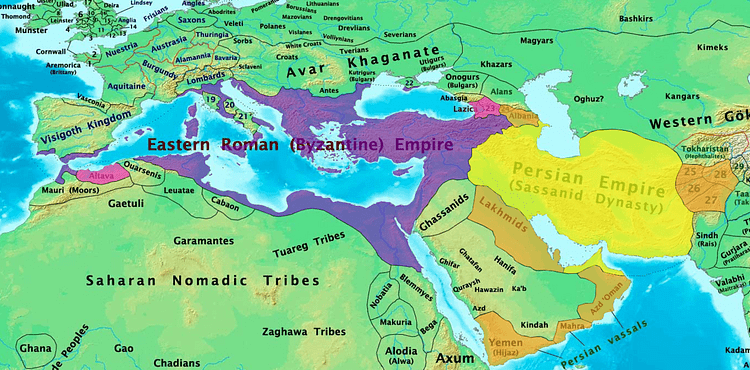

Hormizd IV's death did nothing to resolve the situation and Bahram Chobin now challenged Kosrau II, forcing him to flee for safety to Constantinople for protection under the emperor Maurice (r. 582-602). In return for this favor, Maurice required the surrender of a number of significant regions in Mesopotamia, Armenia, and the strategically important fortress of Dara. In agreeing to this, Kosrau II was essentially handing the Byzantines the keys to his empire but he was in no position to negotiate.

With Maurice's backing, Kosrau II marched back into his territory and defeated Bahram, who was later assassinated. He received a gift of 1,000 warriors from Maurice to serve as his personal bodyguard and seems to have used these men to suppress any other claims to the throne. He maintained close ties with Constantinople and regarded Maurice as his friend and benefactor, and this relationship kept the peace between the two empires for the first twelve years of Kosrau II's reign.

If that model of rule could have continued, Kosrau II would be remembered as one of the great Sassanian kings and the whole history of the region would almost certainly have been different. As it was, however, Maurice was assassinated by one Phocas (r. 602-610) who sent word to the Sassanians that he was the new Byzantine emperor. Kosrau II refused to recognize him, swore he would avenge the death of Maurice, and broke the peace in 602.

The resultant war consistently went in favor of the Sassanians and the Byzantines steadily lost territory. Phocas was finally assassinated in 610 and Heraclius (r. 610-641) came to power, immediately sending envoys to Kosrau II to end hostilities. Kosrau II saw no reason to comply, however, since he was clearly on the verge of destroying the Byzantine Empire and elevating his own to a grandeur surpassing even that of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) of the past.

Kosrau II continued his string of victories largely due to the brilliance of his general Shahrbaraz (d. 630). Heraclius understood that he had to neutralize Shahrbaraz if he hoped to save his empire but had no idea how. Around 620, Kosrau II raided the churches of Mesopotamia and Syria for their treasure to fund his war and Heraclius seized on this, declaring the war now a crusade to preserve Christianity. Shahrbaraz may or may not have been a Christian but he was sympathetic to the Church. Still, this was not enough to turn the general away from his king.

Fortunately for Heraclius, he intercepted a letter from Kosrau II to Shahrbaraz's second-in-command telling him to kill the general and take his position. This letter certainly could have been authentic since it was hardly unprecedented that a sitting monarch would want a popular general removed. This had been exactly the same conflict between Hormizd IV and Bahram Chobin. Heraclius invited Shahrbaraz to a parley at which he showed him the letter and won him to his side.

With Shahrbaraz now fighting for the Byzantines, the Sassanians were steadily defeated. Heraclius again sent envoys to Kosrau II requesting peace and was again rebuffed but the Sassanian nobles understood the way the war was going, staged a coup, and threw Kosrau II in prison. His stepson Sheroe (also given as Shiroe) was crowned as Kavad II in 628.

Civil War

Kavad II almost instantly had all of his brothers, half-brothers, and stepbrothers executed beginning with Mardan, Kosrau II's favorite son and heir to the throne. He allegedly had each of them killed in front of their father in his prison cell before finally torturing and killing him. Afterwards, he concluded a peace with Heraclius, ending a war which had severely weakened both empires after almost 30 continuous years of conflict.

Once he had consolidated power, Kavad II initiated policies of reconciliation and reconstruction and perhaps could have redeemed himself for the slaughter of his family in some way but died in 628 from the plague (which was named after him - Sheroe's Plague of 627-628) that swept through the region. The prolonged war, ending in defeat, and Kavad II's senseless and cruel slaughter of his brothers alienated the nobility from the throne and especially so because there was now no one of royal blood to succeed Kavad II except his seven-year-old son Ardashir III (r. 628-629).

The nobles crowned the boy shortly after his father's death but, naturally, he had no real power. The empire was now administered by the vizier Mah-Adur Gushnasp (also given as Mehr Hazez, r. 628-629) who was to act as regent until Ardashir came of age. Mah-Adur Gushnasp's regency restored some semblance of stability and, by all accounts, he ruled with justice and wisdom.

Different noble factions, however, began to disagree on the regency. Two factions – the Parthian and Persian nobility – favored Ardashir III's reign and Mah-Adur-Gushnasp as regent and were initially supported in this by others. After less than a year, however, the Persians withdrew their support and advocated for Purandokht (also known as Boran) the daughter of Kosrau II, as she was of noble blood and also of age to rule.

At this same time, the general Shahrbaraz, who was still in Anatolia, entered into talks with Heraclius who promised to support him if he staged a coup. Precisely why Heraclius was interested in removing Mah-Adur Gushnasp is unclear since the regency was complying easily with the peace. Shahrbaraz then gained the support of some of the disgruntled nobles at Ctesiphon and was able to march into the city in 629, assassinate Ardashir III and Mah-Adur Gushnasp, and declare himself king.

Shahrbaraz was assassinated less than a year later by the noble Farrokh Hormizd who took the throne name Hormizd V (r. 630-631) but supported the reign of Purandokht/Boran (r. 629-631) who, even before Shahrbaraz's assassination, had been recognized as the true monarch by his faction. Purandokht/Boran was deposed in 630 in favor of Shahrbaraz's son but, when this did not placate the divisive nobles, Purandokht/Boran's sister Azarmidokht (r. 630) was made queen. To legitimize his claim to the throne, Farrokh Hormizd asked Azarmidokht to marry him and, rather than risk reprisals by refusing, she had him assassinated. His son, the general Rostam Farrokhzad (d. 636), marched on Ctesiphon to avenge his father. He defeated Azarmidokht's forces, blinded her, and then killed her, restoring Purandokht/Boran to the throne.

Purandokht/Boran made peace with Rostam and his family and did her best to stabilize the empire but the infighting of the different noble factions of Parthians and Persians made this almost impossible. To keep the peace, she declared Rostam the country's true leader as a kind of regent to her reign, but this did not even resolve the conflicts, and she was assassinated in 631. The two factions were now in open civil war but realized that, while they fought, the empire was crumbling. They, therefore, agreed on a peace which was sealed by crowning Kosrau II's grandson (Purandokht/Boran's nephew) king as Yazdegerd III.

Yazdegerd III's Reign

Yazdegerd III succeeded to an empire which had been crumbling even before the end of the Byzantine wars in 628. Sheroe's Plague had killed many and was ongoing in some regions with no efforts made to do anything about it. The nobility under Kosrau II had grown increasingly wealthy at the expense of the lower classes, and Ctesiphon and its environs had been enriched by the labor of the people in the provinces. The tax reforms and changes in the Persian government instituted by Kosrau I had been reworked by the nobility under Kosrau II so that they again benefited the rich, and the Zoroastrian clergy was so corrupt that sects such as Zorvanism and religions including Christianity, Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Judaism were all gaining more adherents which weakened the social structure of the empire by undermining the authority of the state religion.

Kosrau II's wars, however, had done the most damage in terms of defense of the empire and morale of the people. Scholar Kaveh Farrokh writes:

Between them, the Byzantines and the Sassanians had lost well over 400,000 first-rate fighting troops. This resulted in a dangerous military vacuum that was ripe for exploitation by the empire's tribal neighbors, notably the Arabs and the Turks. The severe weakening of Byzantium and Sassanian Persia was well noted by Caliph Omar [Umar] (581-644) and the Arab commanders in Medina. (261)

Yazdegerd III had only been reigning less than a year when the Muslim Arabs under Mosni ibn Haresa took the city of Hira in 633. Rostam Farrokhzad was able to drive them out in 634 but they returned. Although the Sassanian armories held plenty of weapons, there were few people left who were trained well enough in Persian warfare to use them effectively. The Sassanian general Bahram defeated the Arabs in Mesopotamia in 634-635, but this was the exception. Yazdegerd III could order defensive actions and deploy generals but his decrees were of little use with no trained armies to carry them out.

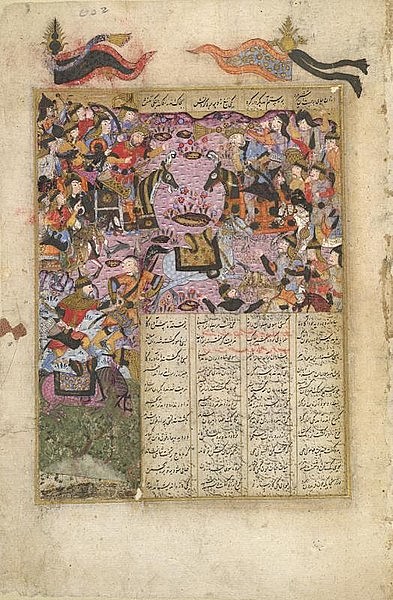

Yazdegerd III deployed Rostam to put an end to the Arab incursions in 636, and he met them under the command of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas (l. 595-674) at the Battle of al-Qadisiyya. Rostam began by opening negotiations and, when that failed, demanded they surrender and withdraw. Waqqas replied that the Sassanians could either convert to Islam, become slaves, or die by the sword.

The battle began in Rostam's favor but the Arabs disabled many of his war elephants and, further, their use of camels in cavalry units on the uneven, sandy, terrain gave them an advantage. The second and third days went first to one side and then to another but, on the fourth day, Rostam broke the Arab lines and was close to victory when a sandstorm erupted, blinding his troops, and allowing the Arabs to regroup. Rostam and his high command were killed and the Sassanian army defeated.

Yazdegerd III, at Ctesiphon, learned of the defeat and fled with his advisors, the remnants of the royal family, and the nobles. When Waqqas arrived, the city was nearly empty and he looted it, sending the goods back to Caliph Umar. Yazdegerd III, meanwhile, desperately tried to gather an army and faced the Arabs again at Jalula in 637 but this battle went no better than the others.

The rest of Yazdegerd III's reign was a series of flights from one location to another. He seems to have frequently alienated his hosts by arriving at their cities and demanding taxes and troops but, considering his circumstances, this is perhaps understandable. He was finally able to raise an army of 150,000 – mostly untrained conscripts – and met the Arabs again at the Battle of Nihavand in 642 where he was completely defeated and the army destroyed.

Yazdegerd III continued his pattern of flight and trying to regroup for the next nine years while the Arabs steadily dismantled the Sassanian Empire. Most of the regional governors at this point felt no allegiance to the crown and offered no resistance to the invaders. Yazdegerd III's constant demands for taxes and troops were received with less and less enthusiasm and, when he finally arrived at Marw in 651 and made these same kinds of requests, he was not received well. He was assassinated soon after, allegedly by a local man, a miller, who only wanted to rob him of his jewelry, though this claim is challenged. Most likely, he was killed by the regional governor of Marw who understood the war was lost and was offended by Yazdegerd III's desperate and, by this time, unrealistic demands.

Conclusion

After his death, his son Peroz III (l. 636 - c. 679) fled with the imperial family across the Pamir Mountains into China. He requested sanctuary and, in 661, military aid from the Tang Dynasty emperor Gaozong (r. 649-683). Gaozong granted him asylum and welcomed any future refugees from the Sassanian Empire into the city of Zaranj. Peroz III was given the aid he requested but this made no difference to the fate of the empire or the Arab conquerors. His brothers, Narseh II and Bahram VII pursued a similar course with the same results. Yazdegerd III's grandson, Kosrau VI, also continued the war with the Arabs and died, probably in battle, at some unknown date after c. 700.

Once Yazdegerd III was dead and his family fled, the Muslim Arabs completed their conquest by suppressing Persian culture and religion and making good on Waqqas' response to Rostam that the Persians could either convert to Islam, become slaves, or die. Zoroastrian fire temples were destroyed or turned into mosques, Zoroastrian texts burned, and Persian palaces looted.

In time, a legend arose that the daughter of Yazdegerd III, Bibi Shahrbanu (“Lady of the Land” or “Lady of the King's Lands”) was brought to the Muslim Arab court at Medina as a prisoner and was so impressive that she was married to the great hero Husayn ibn Ali (l. 626-680), the Shia Muslim martyr who fell at the Battle of Karbala in 680. There is no record of a daughter by that name – though there may be some historical basis for the legend involving another Persian princess – and the story was most likely created in an attempt to legitimize Muslim Arab rule over Persia after Yazdegerd III had been immortalized as the martyred king of the once-great Sassanian Empire.