Yazidism is a syncretic, monotheistic religion practiced by the Yazidis, an ethnoreligious group which resides primarily in northern Iraq, northern Syria, and southeastern Turkey. Yazidism is considered by its adherents to be the oldest religion in the world and the first truly monotheistic faith. The Yazidi calendar states that the religion, as well as the universe, is almost 7,000 years old, which is 5,000 years older than the Gregorian Calendar and 1,000 years older than the Jewish calendar. Yazidism has had a rich history of syncretic development. For thousands of years, Yazidism incorporated elements of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam, all of which coalesced from 1162 CE to the 15th century CE. Ultimately, this process created Yazidi culture and ethnic identity. However, to understand Yazidism, its history must first be explained.

The Origins of Yazidism

Almost nothing is recorded about the history of the first Yazidis. The etymology of the word 'Yazidi' is uncertain. Scholars debate whether or not it comes from the Middle Persian and Kurdish Yazad, which means 'God.' Other scholars believe that the Yazidis originated in the Zoroastrian city of Yazd in Iran. Another theory is that the Yazidis are descended from the Umayyad caliph Yazid ibn Mu'awiya, who reigned from 680 to 683 CE and killed the Prophet Muhammad's grandson, Hussein ibn 'Ali. After the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 CE, descendants of the royal family and other Umayyad sympathizers fled into the Kurdish mountains from the rival Abbasid Caliphate. There, they were welcomed by the Kurds, who remained loyal to them. The theory concludes that the Umayyad refugees intermarried with the Yazidis, passing along their admiration for Yazid ibn Mua'wiyah, their ancestor and former ruler. This theory is popular among Western scholars, as in Yazidism, the historical figure of Yazid appears as one of the three manifestations of God, Sultan Êzî.

The Yazidis call themselves Ezid, Ezi, or Izid, as well as Dasini or Dasin, which is linked with the Nestorian Christian dioceses of Daseni or Dasaniyat. There is substantial evidence for the emergence of aspects of Yazidism from Christianity, as certain Yazidi rituals are derived from Christian traditions, such as baptism and the consumption of alcohol.

The Yazidis were first recorded historically by Muslim historian 'Abd al-Karim al-Sam'ani (d. 1167 CE) as a community in Iraq during the 12th century CE. He wrote of a community called al-Yazidiyya in the region of Hulwan in northern Mosul, Iraq. He said that they lived an ascetic lifestyle and rarely associated with outsiders. He also stated that al-Yazidiyya revered the caliph Yazid ibn Mu'awiya, which is consistent with modern Yazidi beliefs. The Christian scholar Gregorius bar Hebraeus (d. 1286 CE) and Shafi'i scholar Ibn Kathir (1301-1373 CE) mentioned that there were many Kurds in northern Iraq who still practiced pre-Islamic faiths, such as the Zoroastrian Taïrahites and the Tirhiye, who practiced an ancient religion called Magism. Another related people known as the Shamsani practiced Manichaeism. However, in the early 12th century CE, the arrival of one man in the Kurdish Mountains would change the fate of the Kurds forever, the man who is credited by scholars and Yazidis as the founder of Yazidism itself: Sheikh 'Adi.

Sheikh 'Adi was a 12th-century CE Sufi mystic who studied in Baghdad with other scholars of Islamic mysticism. Amongst these were the sheikhs 'Uqayl al-Manbiji and Abdu'l-Wafa al-Hulwani, who came from the Kurdish mountains and established a Sufi presence there. This inspired 'Adi to travel to northern Iraq to lead an ascetic life, free of all desires and the self.

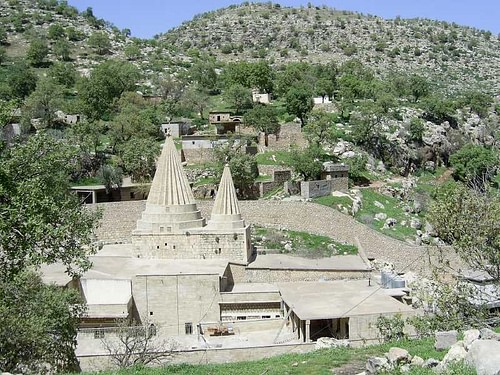

Sheikh 'Adi left Baghdad in the early 12th century CE to found a convent of Dervishes, or Sufi Muslim ascetics, in the valley of Lalish. He found a group of peasant Kurds in the area, whose belief system was a mixture of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, ancient Iranian religions, and the veneration of the Umayyad caliph Yazid ibn Mu'awiya. Sheikh 'Adi performed miracles and led an ascetic lifestyle, which moved the Kurdish peasants so much that they became his followers. 'Adi taught them his mystical form of Islam until he died in Lalish in 1162 CE. His tomb became a site of pilgrimage for his followers. Eventually, 'Adi's followers turned the qibla, the direction in which a Muslim prays, away from Mecca and towards Lalish. This was the first step in the development of the Yazidi religion away from Islam, and Sheikh 'Adi's followers began calling themselves 'Yazidis.'

Years later, Sheikh Hasan, the grandson of Sheikh 'Adi's nephew, expanded Yazidi influence throughout the Muslim world during the 13th century CE. According to Yazidi oral tradition, Hasan wrote the religious text Kitab al-Jilwa li-Arbab al-Khalwa, which put Sheikh 'Adi's ideas into written form. During Hasan's reign, Yazidis served as soldiers in Saladin's Muslim army during the Crusades and served as ambassadors to the Ayyubid Sultanate. Yazidism itself spread throughout the Kurdish community, and many converted. The Yazidis emigrated to large swathes of the Muslim world.

The increased power of the Yazidis under Sheikh Hasan frightened many Muslims, especially Badr al-Din Lu'lu, the provincial governor of Mosul. The Yazidis and the majority of other Kurdish groups did not support his rule; they rebelled and refused to pay taxes. Lu'lu feared a large Kurdish revolt under the leadership of Hasan, so he sent his army to kill and imprison the Kurds. His soldiers did so and burned Sheikh 'Adi's bones in Lalish. Sheikh Hasan was captured and decapitated in Mosul in 1253 CE. The execution of Sheikh Hasan marked the beginning of centuries of persecution faced by Yazidis, which has continued into the 21st century CE. By the 14th century CE, Yazidism spanned from the city of Sulaimaniya in the Kurdish Mountains to Antioch in Turkey. However, Yazidis have lived in tribal societies from the 15th century CE onwards as a result of continued persecution and a lack of centralized leadership.

Yazidi Religion & Its Tenets

During its 300-year period of syncretization from 1162 CE to the 15th century CE, Yazidism began to drastically deviate from Islam. Yazidis drank alcohol and turned the direction in which they prayed away from Mecca and towards Sheikh 'Adi's tomb, activities which Muslims despised. Yet, Yazidism and Islam were and still are both monotheistic. In Islam, God's 'one-ness,' or tawhid, is paramount. Tawhid means that God has no relatives or family members, nothing is comparable to him, and he is indivisible, which means that he cannot be comprised of a Holy Trinity. Thus, tawhid means that God is the only deity in the universe, the paragon of monotheism. The religious studies scholar Huston Smith said the following about the Islamic perception of God:

This God, whose majesty overflowed a desert cave to fill all heaven and earth, was surely not a god or even the greatest of gods. He was what his name literally claimed: he was the God, One and only, One without rival. Soon from this mountain cave was to sound the greatest phrase of the Arabic language; the deep, electrifying cry that was to rally a people and explode their power to the limits of the known world: La ilaha illa 'llah! There is no god but God! (Smith, 225)

Similarly, Yazidis believe in the existence of one God named Xwedê. He is a benevolent, all-forgiving, and merciful deity, as well as the creator of the universe. According to Yazidi oral tradition, which is how Yazidism is transmitted to successive generations, Xwedê created the world by making a white pearl. He then created the first bird, Anfar, and put the pearl on its back for 40,000 years. It was from this process that Earth emerged.

Xwedê's attributes are elaborated upon in two Yazidi religious texts: the Kitab al-Jilwah and the Mishefa Resh. Even though they were compiled by Western scholars, the contents of the Kitab al-Jilwah and Mishefa Resh corroborate Yazidi oral tradition and can therefore be seen as authentic. In the Kitab al-Jilwah, God states,

I was, am now, and shall have no end. I exercise dominion over all creatures and over the affairs of all who are under the protection of my image. I am ever present to help all who trust in me and call upon me in their time of need… To me truth and falsehood are known. (Joseph, 30)

Therefore, Yazidis envision God as omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient, which is the same way Muslims view Allah. Additionally, the God of Yazidism also grants human beings free will, a theological concept also found in Christianity and Islam. God says in the second Yazidi holy book, the Mishefa Resh, “I allow everyone to follow the dictates of his own nature, but he that opposes me will regret it sorely” (Joseph, 30). Additionally, the Yazidi God, like Allah, cannot be perceived by humans and can punish those who violate his will.

Even though Yazidism and Islam share some similarities, the former diverges from the latter in terms of how Yazidis perceive God. While God is monotheistic, he is comprised of a Holy Trinity, which features the Peacock Angel ('Peacock Angel' is Tawusi Melek in Kurdish), Sheikh 'Adi, and Sultan Êzî. In the Trinity, 'Adi and Êzî are deified versions of their historical counterparts: Sheikh 'Adi is the Sufi mystic and preacher who taught the Yazidis' Kurdish ancestors his version of Islam, while Sultan Êzî is the Umayyad caliph Yazid ibn Mu'awiya. The Peacock Angel, however, is the chief member of the Holy Trinity. He is a manifestation of God and the ambassador to humanity, tasked with bestowing divine wisdom upon the Yazidi people every 1,000 years. As the leader of the Heft Sir (Seven Angels), the Peacock Angel and his subordinates are responsible for predetermining the future. Yazidis view him as the symbol of their faith. As the only earthly representative of God, he is deeply revered. The Yazidi Holy Trinity is the only way through which God can be observed, and the Trinity is the object of veneration. The Yazidi hymn 'Symbol of Faith', or Ședha Dînî, states:

The testimony of my faith is One God,

Sultan Sheikh 'Adī is my king,

Sultan Ězî is my king,

Tawûsî Melek is (the object of) my declaration and my faith.

God willing, we are Yazidis

Followers of the name of Sultan Ězîd.

God be praised, we are content with our religion and our community.

(Açıkyıldız, 71-72)

Theology of the Peacock Angel: Accusations of Devil-Worship

While Yazidism's Holy Trinity distinguishes it from Islam, the greatest theological difference between the two faiths is how the Peacock Angel contrasts with the Islamic view of Satan. Yazidi oral tradition states that God ordered the Peacock Angel not to submit to other beings. God then tested his loyalty by creating Adam, the first man, from dust, and subsequently commanded the Peacock Angel to bow to Adam. However, the Peacock Angel refused, exclaiming, “How can I submit to another being! I am from your illumination while Adam is made of dust” (Williams). Consequently, God praised the Peacock Angel and made him his earthly representative. Thus, Yazidis interpret the Peacock Angel's rejection of Adam as the purest act of devotion to God.

Muslims, however, view the Peacock Angel's refusal to submit to Adam as heretical. They equate him with Satan (who is also called 'Iblis' in the Qur'an), who, like the Peacock Angel, refused Allah's command to submit to Adam. However, instead of praising him, Allah cast Satan into Hell as a punishment for disobeying his command. In the Qur'an, God states:

We said, 'Bow down before Adam,' and they all bowed down, but not Iblis: he was one of the jinn and disobeyed his Lord's command. Are you [people] going to take him and his offspring as your masters instead of Me, even though they are your enemies? What a bad bargain for the evildoers! I did not make them witnesses to the creation of the heavens and earth, nor to their own creation… We shall set a deadly gulf between them. The evildoers will see the Fire and they will realize that they are about to fall into it: they will find no escape from it. (Qur'an 18:50-53)

Because of this parallel between the Peacock Angel and Satan, many Muslims and Christians have accused Yazidis of being devil-worshippers. This accusation is baseless, as not only is the Peacock Angel a distinct entity from Satan in Yazidism but the concept of 'Satan' does not exist in the Yazidi faith. In fact, Yazidis are forbidden from saying the word 'Satan' or words that sound like Satan because doing so would associate Satan's evil characteristics with the Peacock Angel. The Mishefa Resh states: “None of us is allowed to utter [Satan's] name, nor anything that resembles it, such as Sheitan (Satan), kaitan (cord), shar (evil), shat (river), and the like” (Joseph, 40).

Despite this key theological nuance, however, the Yazidis have been persecuted by Muslims and Christians for centuries because non-Yazidis have wrongly identified the Peacock Angel as Satan. The Yazidis have endured 74 attempted genocides, the most recent of which was at the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, which began in 2014 CE and continues to the present day.

Yazidism: A Guarded Faith

Yazidis are immensely secretive about their traditions and religious beliefs, which are orally passed down from generation to generation by a special priestly caste known as qewwals. Yazidis prevent outsiders from learning about and participating in their holiest traditions. Additionally, Yazidi marriage is endogamous in order to maintain purity of belief, customs, and group safety. If a Yazidi marries a non-Yazidi, he or she is deemed an outsider and is barred from the faith. While this extreme level of secrecy might be surprising to some, it is rooted in a history of persecution, bloodshed, and uncertainty. The Yazidis have managed to survive numerous attempts at extermination for centuries, but such brutality has left deep cultural scars. Modern-day Yazidis solemnly remember their brethren who have been lost to violence throughout their history. However, they also look to the future, instructing the young about the tenets of Yazidism and hoping for the day that they can finally practice their religion in peace.