The Yongle Emperor (aka Chengzu or Yung Lo, r. 1403-1424 CE) was the third ruler of the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Inheriting a stable state thanks to the work of his father, the Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368-1398 CE), Yongle made lasting contributions to Chinese history such as moving the capital to Beijing and beginning construction of the Forbidden City as an imperial residence. The emperor also opened up China to the world, notably sponsoring the seven voyages of the explorer Zheng He. However, costly wars in both the south and north of China and the expense of his grandiose construction projects would leave Emperor Yongle's successors with less cash than they needed to face the resurgent Mongols of the mid-15th century CE.

Zhu Di Takes the Throne

The founder of the Ming Dynasty was the Hongwu Emperor, and it was he, after 30 years of rule from 1368 CE, who sparked off a rumpus at the imperial court over who should be the next ruler. The problem was that although Hongwu had 26 sons, the carefully groomed heir, his first son Zhu Biao, had died prematurely in 1392 CE. Instead of choosing his own second eldest son, Hongwu decided on the eldest son of Zhu Biao. Indeed, this became the convention throughout the Ming dynasty - the eldest son of the Empress would inherit the throne, and if he died before this was possible, the right went to his eldest son. Thus, when Hongwu died in 1398 CE, he was succeeded by Zhu Yunwen (aka Huidi), who took the reign name of the Jianwen Emperor (r. 1398-1402 CE).

This jumping of a generation did not go down well with Hongwu's second son, known as the Prince of Yan (and as Zhu Di, b. 1360 CE) who had high ambitions of his own. The prince commanded a large army, which had won many victories against the Mongols, and he was prepared to press his claim by force. After a three-year civil war, the Prince of Yan was the victor, and he became Emperor Chengzu, taking the reign name Yongle Emperor, meaning 'Eternal Contentment' or 'Eternal Joy'. The Jianwen Emperor simply disappeared, perhaps killed during the war in a fire in the palace of Nanjing or, more intriguingly, he may have escaped the city disguised as a monk. Whatever his fate, nothing more was ever heard of the Ming Dynasty's second emperor.

Consolidating Power

Just as ruthless as his father had been in eliminating any dissent in the state bureaucracy, Yongle started with a clean sweep of any official he thought loyal to his nephew Jianwen. In one infamous purge begun right after the new emperor took office, the noted Confucian scholar-official Fang Xiarou, who had refused to draft the proclamation of Yongle's enthronement, was executed by dismemberment. Any of Xiarou's known associates in the government were executed and so too all his relatives to the tenth degree. On top of all those victims, the emperor ordered the execution of all the officials who had passed their civil service examinations while Xiarou had been their overseer. The death toll ran into the thousands.

Despite the huge number of officials who were removed from office by the emperor's purge, the state bureaucracy was expanded; eunuchs especially gained power and influence because, unable to have children, their loyalty was considered more certain than other officials. Indeed, in 1420 CE, the emperor established a sort of secret service headed by his chief eunuch. This service, called the Eastern Depot, was set the task of rooting out any lingering opposition to Yongle's legitimacy to rule and eliminate corruption. Another branch of the bureaucracy, the state archives and repository of official histories, was given the task of all but blanking out Jianwen's reign and falsifying records to show that Yongle had the legitimate claim to the throne.

Beijing & The Forbidden City

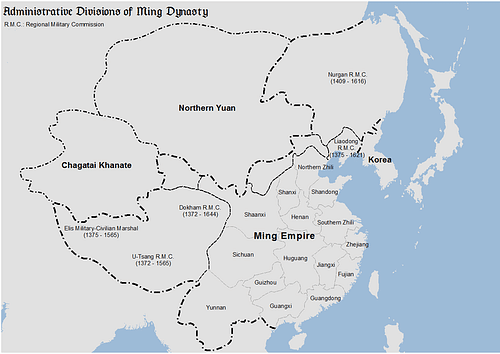

In the early 15th century CE the Mongols experienced a resurgence on China's borders and so Emperor Yongle moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1421 CE to be better placed to deal with any foreign threat. The site had a history as an ancient capital under various regimes, and it was also in the province that the emperor had personally commanded when he had been the Prince of Yan. At huge expense, Beijing was enlarged and surrounded by a 10-metre high circuit wall measuring some 15 kilometres in total length. Accessed by nine gates, the city was laid out on a regular grid plan. Such was Beijing's need for food, the Grand Canal was deepened and widened so that grain ships could easily reach the capital.

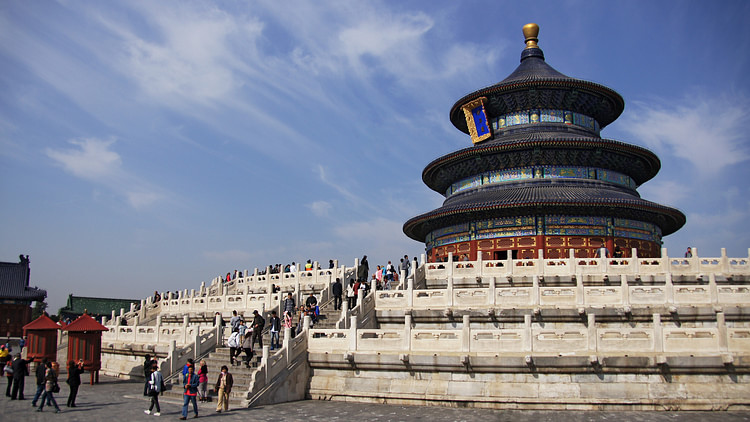

One of the lasting contributions to Chinese history made by Yongle was the building of the Forbidden City in the heart of Beijing, built as the imperial residence. Known in Chinese as Zijincheng ('Purple Forbidden City'), construction was begun in 1407 CE, and thousands of labourers spent the next 14 years creating one of the greatest cities in the world. The buildings, set upon white stone slabs, were made of painted red wood and yellow glazed ceramic roof tiles and surrounded by a high wall. Besides functional buildings, there were huge open squares, pavilions, ornamental gardens, canals, bridges, and pagodas. The whole ensemble was designed to leave a visitor in no doubt of the power of the ruler who could build such a complex. Used also by the emperors of the Qing dynasty, the Forbidden City was continuously extended and restored until reaching its present impressive spread of some 7.2 square kilometres.

No fewer than 24 emperors would reside in the Forbidden City. The buildings and their thousands of rooms are all carefully laid out in a plan which reflects the traditional Chinese view of the world. At the heart of the complex, on the most elevated site, is the Hall of Supreme Harmony, where imperial receptions were held. Other halls spread outwards from this central point, all built along a north-south axis. The emperor himself and all male attendants lived in buildings on the eastern side while women lived on the western side of the complex. The Forbidden City also included government offices, all arranged strictly according to the rank of officials. Needless to say, the forbidden aspect derives from the controlled access to it, with only officials of certain ranks and invited ambassadors being permitted within its walls. Today the complex contains the largest collection of imperial treasures and artworks in China.

Zheng He & the End of Isolationism

The Yongle Emperor did not wait long before he embarked on a much more aggressive foreign policy than his predecessors and end the isolationism begun by his father. In 1406 CE he sent an army to invade a then-independent Vietnam. The campaign was successful, although the country would regain its independence 20 years later. There would also be several campaigns against the Mongols to ensure China's northern borders were respected, but the enemy's tactics of retreating on horseback whenever threatened meant that nothing was ever really achieved in the expensive campaigns. The least successful military operation was the attempt to annex Annam on the south-west border of Ming China which resulted in a two-decade military stalemate that once again drained imperial resources.

A more peaceful and successful strategy of Emperor Yongle to foster new international relations was his use of diplomatic missions. Ambassadors were sent to Herat and Samarkand in central Asia, as well as to Manchuria, Tibet, and Korea, all with some success. The most famous of these missions, though, was the adventures of Zheng He (1371-1433 CE), widely regarded as China's greatest ever explorer. Born in Yunnan in southern China, Zheng was a eunuch Muslim who rose to become an admiral in the imperial fleet. The Yongle Emperor sent Zheng on seven diplomatic voyages between 1405 and 1433 CE, with each voyage involving several hundred ships. Zheng sailed along established routes to the coast of India, the Persian Gulf, and the east coast of Africa, but many of his final destinations were new points of contact for the Chinese.

The intention was that the voyages of Zheng He, giving out lavish gifts like silk and fine Ming porcelain as well as letters of friendship from the emperor, would encourage East Asia back into the sphere of the Chinese tribute system and extend that system to new states as remote as East Africa. The tribute system, rather than a means for China to acquire free goods, was really only a gratification of the Chinese belief that they were the centre of the world and their ruler was the Son of Heaven. The presence of foreign ambassadors in the Forbidden City would also help Yongle legitimise his own position as emperor, taken as it had been by force from his own nephew. Indeed, some scholars have suggested that part of Zheng He's mission was to find out if the Jianwen Emperor really was in hiding somewhere in Southeast Asia and plotting a comeback.

Ultimately, the voyages of Zheng He only managed to woo East Asian rulers to consistently pay tribute, but Zheng certainly brought back plenty of knowledge of foreign lands and customs, and he did ship back such exotica as giraffes, gems, and spices. The voyages were extremely costly, though, and Yongle's successors would abandon the idea, at least in terms of those lands across the Indian Ocean.

The Yongle Dadian Encyclopedia

Previous Chinese dynasties had created encyclopedias, but during Yongle's reign one of the biggest ever was produced. The massive Yongle Dadian covered all important Chinese literary works that had survived up to that point. Compiled by 147 scholars and then revised by another 3000, the work had well over 22,000 chapters; the index alone took up 60 chapters. Too large to be printed, unfortunately, most of the original was lost in the strife at the end of Ming dynasty and that of a copy in a fire during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901 CE). Around 800 chapters of the encyclopedia do still exist in various libraries outside of China.

Death & Successors

Although the Ming benefitted from the divisions within the Mongol state - generally split into six competing groups - there were still sporadic attacks on Chinese territory throughout Yongle's reign. As a consequence, the capital was moved to the north, as already mentioned, and the Great Wall of China was also repaired as a defence against Mongol raiders. The danger never went away, though, and the Yongle Emperor died in 1424 CE while on an expedition fighting one such Mongol incursion. It was the emperor's fifth such campaign and he ultimately paid the price for leading his army in person on the battlefield, as he had done ever since his days as a prince. Yongle died aged 64, and he was succeeded by his son, known as the Hongxi Emperor. After Hongxi died following a heart attack just one year into his reign, the next emperor was Xuande, the Yongle Emperor's grandson, who would reign until 1435 CE. Xuande and his successors would continue the work of Yongle and ensure Ming China became one of the richest and most powerful states in the world, more than doubling its population to around 200 million people.