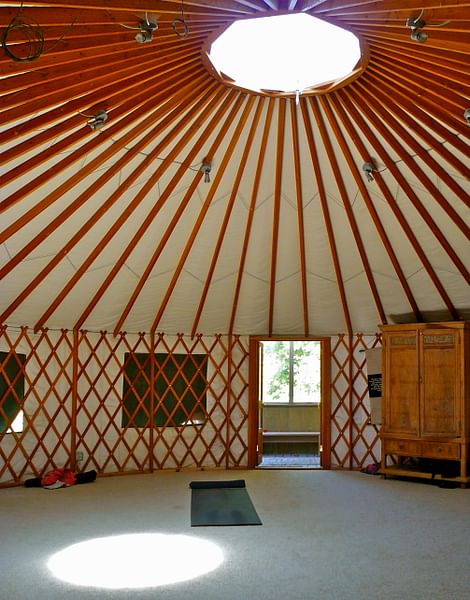

A yurt (ger in Mongolian) is a large circular tent made of wool felt stretched over a wooden frame used by nomadic peoples of the Asian steppe since before written records began. Yurts are especially associated with Mongol herders and hunters and were famously used by such figures as Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE). Made in various sizes and even sometimes permanently erected on top of carts for ease of mobility, yurts have become one of the identifying features of the nomads who still today carve out a living in the often harsh climate of the remotest parts of Eurasia.

Name

The yurt tent has been used by nomadic pastoralist peoples of northern East Asia since before written records began. They provided a semi-temporary home which was both practical and light enough to be transported when tribes moved on with their herds to find new pastures. The name yurt is the more familiar name in the West and derives from the Russian yurta. However, the Russian term itself derives from the Turkic word jurt which means 'people' or the territory on which they roam. In Mongolian, the name of the tent is ger, meaning 'home.'

Design & Materials

During the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) and before, the skin of the yurt tent traditionally consisted of layers of felt which were made from beaten sheep's wool (by crushing wool, microscopic barbs in the fibres interlock and so a solid cloth is formed). The sheep herded by the Mongols did not produce wool suitable for weaving and this same felt was used for many other purposes such as clothing and blankets. The felt was then made waterproof by adding sheep's milk or fat. This process also made the material a better insulator and protected the wool from the elements. Nowadays, alternative materials may be used.

The felt or substitute material is spread over a wooden lattice framework topped by a wooden ring. The outer walls were sometimes decorated with embroidered geometric designs or representations of local flora and fauna. The very centre of the rooftop was left open as a means for light to enter and smoke from the hearth within the yurt to escape - a sensible design given that the fuel burned was often dried dung bricks. The flattish top of the yurt also proved a handy place to cure and preserve the nomad's cheese in the wind and sun. The door and door frame of the tent - usually arranged to face the south - is typically made of wood and there may also be a wooden base. The size of the yurt varies, and those used in the medieval period and earlier were likely much larger than those still in use today, which are typically inhabited by a single small family.

Yurt Camps

Although a family can erect a yurt in just one hour and when taken down it can easily be packed onto a horse, camel, or cart, there was (and still is) an even more convenient option. A specific type of yurt seen in the medieval period was the khibitkha (or ger tergen) which was permanently mounted onto a cart. These especially wide carts could be massive and were pulled by a large team or even several teams of yoked oxen when required. The 13th-century CE chronicler William of Rubruck recorded that he had seen wagons used for this purpose with axles 'as large as ship's masts' which were pulled by up to 22 oxen (quoted in Lane, 52). There are also stories, such as that of Shiremun, the grandson of Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE), using wagoned yurts as a means to secretly transport troops to a meeting of Mongol tribal chiefs during the many bitter succession conflicts which wracked the empire each time a khan died.

A khibitikha was an expensive luxury and reserved for the elite such as clan leaders and tribal chiefs. Likewise, more senior families of a tribe might have several yurts each and these could be used to house separately different members of the group such as older children, bodyguards, servants, and junior wives. The positioning of the yurts in a camp (ordu) was also important in imperial and larger camps with the senior wife having the tent nearest to the west, the most junior wife to the east and the concubines, children and servants someway behind.

The traditional procedure to make camp for more ordinary nomads was to create a perimeter circle of yurts, within which were positioned the vehicles and livestock of the tribe. This arrangement was known as a gure'en but, as most nomads lived in small groups so as not to overburden the pasture in any particular area, it was really only a strategy employed by senior chieftains and at larger gatherings such as seasonal or annual tribal meetings. The imperial camps, where the khan himself was present, seem to have had the opposite arrangement with the wagons forming an outer square perimeter to the yurts within. The yurt of the tribe's chief was typically set up in the centre of the camp while the khan moved about each night depending which wife he fancied spending time with. The term gure'en later came to be applied to any fortified camp and then to the standard social and military unit of the Mongol Empire, the 'thousand', which was also called a mingan.

The Evolution of Yurts

The yurt was obviously essential to a family's well-being, although there was a curious tradition amongst the Mongols that the youngest son inherited his father's yurt and personal possessions. Even a basic yurt was a valuable commodity, but by the time the Mongols had established their empire, some of these tents became very splendid objects indeed. Typically white on the outside thanks to a chalk, clay, or powdered bone covering, they were lavishly decorated inside with gold brocade, jewels, and pearls, while the flooring consisted of fine carpets. In the mid-13th century CE, the Mongol governor at Samarkand, Mas'ud Beg, had a tent woven entirely from silk and gold while the governor of Khorasan's tent was reportedly held together using 1,000 gold nails.

Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire, famously lived in a yurt throughout his reign and shunned the idea of living in a palace - a favouring of simplicity that his successors abandoned as they preferred to live in more permanent structures. Even Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE), though, who had the most sumptuous palace of all at his capital Xanadu (Shangdu), could not quite do without the charm of a yurt, and he kept several in his hunting park and even sometimes slept in one set up in his royal residence. The Khan had another set of tents in Beijing where he went one step further and recreated an entire steppe landscape by carting in tons of steppe soil, flora, and even automaton tigers.

There is archaeological evidence that even when cities were conquered, the nomadic Mongols sometimes set up their yurts within the destroyed city walls, as at 13th-century CE Sarai, for example, where yurts were set up in many villa gardens. Yurts continued to be used in such urban settings for feasts, formal audiences, as guest houses and for women about to give birth. It seems then that the yurt was such a part of the identity of steppe peoples that it proved very difficult to abandon for more modern and spacious alternatives.

Still today, yurts, besides their appeal to tourists eager to live for a while in a traditional abode, continue to be used by nomadic peoples in such places as the Gobi desert for their practical functionality, even if now they might sport such fancy additions as aluminium chimneys and solar panels.