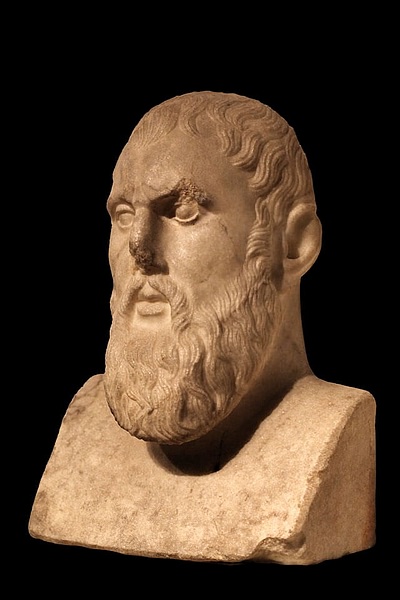

![Zeno of Citium [Pushkin Cast] (by shakko, CC BY-SA) Zeno of Citium [Pushkin Cast] (by shakko, CC BY-SA)](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/352.jpg?v=1618780502)

Zeno of Citium (l. c. 336-265 BCE) was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy in Athens, which taught that the Logos (Universal Reason) was the greatest good in life and living in accordance with reason was the purpose of human life.

If one lived according to the instinct of impulse and passion, one was no more than an animal; if one lived in accordance with universal reason, one was truly a human being living a worthwhile existence. This philosophy would later be developed by the Stoic philosopher Epictetus (l. c. 50-130 CE) and others and would have a significant impact on the people of Rome, most notably the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE). Stoicism would eventually become one of the most popular and influential philosophies in the Roman world.

Zeno was a merchant until he was exposed to the teachings of Socrates (l. c. 470/469 to 399 BCE), the iconic Greek philosopher through a book by one of Socrates' students, Xenophon (l. 430 to c. 354 BCE), known as the Memorabilia. This book contained conversations with Socrates, his philosophy, and Xenophon's memories of the time spent as his student. Zeno was so completely captivated by the work that he left his former profession and dedicated himself to the study of philosophy, eventually becoming a teacher himself. His school would eventually influence the development of Roman philosophy when one of its students, Diogenes of Babylon (l. c. 230 to c. 140 BCE), brought Stoicism to Rome in 155 BCE.

Early Life

Zeno was born in the Phoenician-Greek city of Citium on Cyprus in the same year that Alexander the Great ascended to the throne of Macedonia. His father was a merchant who traveled often to Athens and Zeno, naturally, took up his father's profession. It is unclear whether Zeno studied philosophy in his youth but, around the age of 22, while stranded in Athens after a shipwreck, he picked up a copy of Xenophon's Memorabilia and was so impressed by the figure of Socrates that he abandoned his former life and made the study of philosophy his only interest.

Zeno studied under Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360-280 BCE) and then under Stilpo the Megarian and then became the pupil of Polemo. From each of these men, he learned some different aspect and nuance of the life of a philosopher. From Stilpo, for example, it is said he learned that the greatest fault in life lay in saying 'yes' too quickly to any request and one should avoid doing so in order to live a tranquil life. In this, he pre-dates Sartre's assertion that saying 'no' is an assertion of one's personal identity while agreeing to another's request diminishes the individual personality. After many years of study, Zeno set up his own school and began to teach on the porches (the 'stoa') of the arcade in the marketplace in Athens and so his school took the name of the place of learning, Stoic.

Student & Teacher

It is traditionally held that Zeno said, more than once, "I made a prosperous voyage when I was shipwrecked," and by this, he meant that, prior to his coming to Athens, his life had no meaning. The discipline of philosophy gave Zeno a focus he seems to have lacked as a merchant and he devoted himself to study and, more importantly, to living the values he absorbed from his teachers and the books he read.

Professor Forrest E. Baird writes that Zeno "argued that virtue, not pleasure, was the only good and that natural law, not the random swerving of atoms, was the key principle of the universe" (505). He was praised highly by the Athenians for his temperance, his consistency in living what he taught, and his good effect on the youth of the city.

Zeno never seems to have been one to hold his tongue when he saw what he perceived as foolishness in the youths around him and many of his remarks sound similar in tone to statements Diogenes of Sinope (l. c. 404-323 BCE) would have made. Unlike the "mad Socrates" of the Agora (as Diogenes was known), Zeno lived a life of traditional, Athenian, respectability while refusing to compromise his principles for what society valued.

Zeno's Philosophy

It was clear to Zeno that most of the people of Athens suffered because they desired what they did not have or feared losing what they loved. The pursuit of pleasure, as espoused by the Epicurean's philosophy (which sprang from the Cyrenaic school of Aristippus, l. c. 435-356 BCE, another of Socrates' students) could never possibly satisfy a human being because one would always be chasing after what one desired or trying to hold on to what one had already obtained. Instead of pleasure, one should court reason and recognize that all things are impermanent and without lasting value.

Once one understood this, one would achieve a state of enlightened apathy in which one would be set free from "enslavement to one's passions" (Mautner, 607). This belief is what made the Stoic school so popular to the Greeks of the time and, later, to the Romans: Zeno's teachings cleared the mind and allowed one to see beyond what one thinks one wants to recognize all that one actually needs - which is simply the self. If one is self-aware, one is also aware of others and, further, recognizes that it is in simplicity that true contentment may be found. These teachings, of course, are more well known today as the basic tenets of Buddhism but were also advocated by a number of the Pre-Socratic philosophers of Greece.

The ancient writer Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 180-240 CE) preserved some of Zeno's teachings in his work Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. He writes that Zeno claimed:

As for the assertion made by some people that pleasure is the object to which the first impulse of animals is directed, it is shown by the Stoics to be false. For pleasure, if it is really felt, they declare to be a by-product, which never comes until nature by itself has sought and found the means suitable to the animal's existence or constitution; it is an aftermath comparable to the condition of animals thriving and plants in full bloom. And nature, they say, made no difference originally between plants and animals, for she regulates the life of plants too, in their case without impulse and sensation, just as also certain processes go on of a vegetative kind in us. But when in the case of animals impulse has been superadded, whereby they are enabled to go in quest of their proper aliment, for them, say the stoics, Nature's rule is to follow the direction of impulse. But when reason by way of a more perfect leadership has been bestowed on the beings we call rational, for them life according to reason rightly becomes the natural life. For reason supervenes to shape impulse scientifically (Baird, 507).

In this, Zeno is simply saying that animals pursue pleasure because they are governed by instinct which drives them to impulse; but human beings, since they have been given reason, ought to be governed by rational thought and live reasonably. To pursue pleasure as the meaning of life, and think that one is living well, is to be no more than an animal or, as Shakespeare later phrases it in Hamlet:

What is a man, if his chief good and market of his time be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more. Sure he that made us with such large discourse, looking before and after, gave us not that capability and god-like reason to fust in us unused. (Act IV.iv.33-39)

To be a true human being, one needed to behave like a true human being: rationally.

Zeno's Republic

When he studied under Crates of Thebes, Zeno wrote his Republic which is quite a different vision of the perfect society than the ideal city-state as imagined by Plato in his work of the same name. Zeno's Republic is a utopia whose citizens claim the universe as their home and where everyone lives in accordance with natural laws and rational understanding. Men and women were completely equal in society's eyes and there was no injustice because all actions proceeded from reason.

There were no laws necessary because there was no crime and, because everyone's needs were taken care of in the same way that animals are in nature, there was no greed nor covetousness nor hatred of any kind. Love governed all things and everyone living in this cosmopolis understood they had what they needed and wanted for nothing more.

It is thought that this vision was largely inspired by Crates' life and that of his wife Hipparchia of Maroneia who lived on completely equal terms with him, wore men's clothes, and taught philosophy to men. Crates and Hipparchia lived their lives in accordance with the simplicity of reason and Zeno's vision in his Republic reflects that view. Of Zeno's work, Plutarch later wrote:

It is true indeed that the so much admired Republic of Zeno, first author of the Stoic sect, aims singly at this, that neither in cities nor in towns we should live under laws distinct one from another, but that we should look upon all people in general to be our fellow-countryfolk and citizens, observing one manner of living and one kind of order, like a flock feeding together with equal right in one common pasture. This Zeno wrote, fancying to himself, as in a dream, a certain scheme of civil order, and the image of a philosophical commonwealth.

Conclusion

Zeno lived and taught in Athens from the time he arrived there following his shipwreck until his death. He died, apparently from suicide, after he tripped coming out of school and broke his toe. Lying on the ground, he quoted a line from the Niobe of Timotheus, "I come of my own accord; why call me thus?" and then, interpreting the accident as a sign he should depart, strangled himself.

While this may seem a strange end to the life of a man who preached the primacy of reason, it would not have seemed so to him. When some happy period of one's life ends, it is irrational to cling to the past and wish it would return; nothing can make that time come again, and longing for an impossible past only robs one of the present. Zeno was an old man when he is said to have broken his toe, and realizing that he had lived a good and meaningful life in Athens, he may have simply concluded that it was time for him to move on to something, and somewhere, else.