Zephyrus was the god of the west wind and the messenger of spring in Greek mythology. He was known as one of the four Anemoi, or wind gods, each of whom represented a cardinal direction and, except for Eurus, a season. Zephyrus was often thought of as the gentlest of the four, although he possessed a capacity for jealousy.

In myth, Zephyrus could be both helpful and vindictive. As the bringer of spring, he was often looked upon favorably by classical writers and poets who wrote of his sweet westerly breeze. He had three different wives, depending on the story, and had offspring with each, including Balius and Xanthus, the immortal horses who pulled Achilles' chariot during the Trojan War.

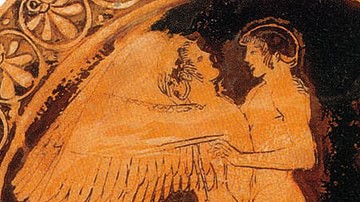

Zephyrus is often depicted in classical art as a handsome and winged youth. Many ancient Greek vase paintings which depict unlabeled figures of a winged god embracing a young man are often identified as Zephyrus and Hyacinthus, the youth whose love Zephyrus rivalled Apollo to receive. Zephyrus is also known by the anglicized name of Zephyr and by the name of his Roman counterpart Favonius.

The Anemoi

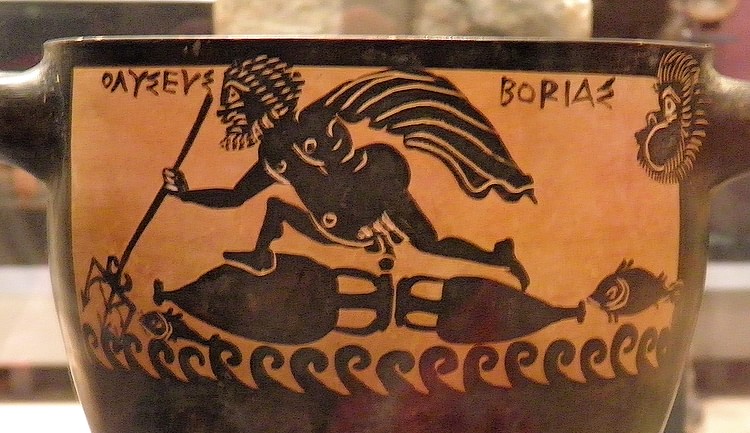

As god of the westerly wind, Zephyrus was one of the four Anemoi, or wind deities. Depicted in various ways, either as winged men or as gusts of wind themselves, each Anemoi was attributed to one of the cardinal directions from where their winds blew. Each of them was also often ascribed a certain season or weather condition. According to Hesiod's Theogony, the four chief Anemoi were the children of two second-generation Titans, Astraeus, the god of dusk, and Eos, the goddess of dawn. In Homer's Odyssey, the Anemoi are subject to Aeolus, the keeper of the winds. The other three Anemoi are Boreas of the north wind, Notus of the south, and Eurus of the east.

In contrast to the gentle nature of his brother Zephyrus, Boreas was known for his strength, violent temper, and capability for great destruction; it was said that during the Persian invasion of Greece, it was Boreas who sank 400 Persian ships during the Battle of Artemisium in 480 BCE. As the god of the cold north wind, he was also known as the bringer of winter and was sometimes depicted with his hair and beard spiked with ice. For a wife, Boreas abducted Orithyia, an Athenian princess. Coming across her dancing beside a stream, Boreas wrapped her in a cloud before carrying her off to the cave in Thrace where he dwelt. Orithyia bore him twin sons, Calais and Zetes. Known as the Boreads, the twins participated in the hunt for the Golden Fleece with Jason and the Argonauts. Due to his marriage with Orithyia, many Athenians considered Boreas a relative by marriage. He was worshipped in Athens, where an annual festival, the Boreasmi, was held in his honor.

Notus, the southerly wind, was associated with late summer and early autumn. He was said to have brought on the hot winds that came after midsummer, and he was seen as the cause of late summer storms, with his scorching winds also having the capacity to ruin crops.

The fourth Anemoi, Eurus, is associated with the easterly wind, although according to some sources it was the southeasterly wind. He is closely connected to the sun god Helios, as his winds came from a place near Helios' palace, from which the sun rose in the east. Eurus is described as being a turbulent wind, causing storms at sea, for which reason he was generally considered to be unlucky. Eurus is the only one of the four main Anemoi not also associated with a season, as well as the only one not mentioned in Hesiod's Theogony.

Zephyrus' Personality, Wives, & Offspring

Zephyrus was often thought to have lived with his brother Boreas in a palace in Thrace, although they were sometimes said to have dwelt in a cave instead. In contrast to Boreas who, possessing a violent temper and great strength, was the bringer of winter, Zephyrus, the gentlest of all the Anemoi, was known as the messenger of spring and early summer. In his Georgics, Virgil (70-19 BCE) writes that "at the Zephyrus' call, joyous summer sends both sheep and goats to the glades and pasture" while "the meadows ungirdle to Zephyrus's balmy breeze; the tender moisture avails for all" (Georgics 3, 322 & Georgics 2, 323). In his Phaedra, Seneca (4 BCE to 65 CE) alludes to Zephyrus' ability to bring forth the season with his breath: "Where meadows lie which Zephyrus soothes with his dew-laden breath and calls forth the herbage of the spring" (Phaedra 11).

In his capacity as the west wind, Zephyrus has been described as light and as the sweetest breeze. Despite this, he did have a hidden strength that was noted by Homer in the Odyssey, where he is referred to as "stormy Zephyrus." This is also occasionally reflected in his personality, as the story of Hyacinthus depicts Zephyrus as jealous and vindictive, a scorned lover.

The west wind was said to have multiple different wives in several stories. He was married to Iris, goddess of the rainbow and a messenger for the gods. As a messenger, Iris was responsible for bearing prayers to her husband, some of which came after especially significant moments in famous Greek stories. It was she who delivered Achilles' prayer to Zephyrus and Boreas to light the funeral pyre of Patroclus, after the young champion's battlefield death in the Iliad. She was also the one to whom Ariadne prays in the 47th book of Nonnus' Dionysiaca, after being abandoned on the island of Naxos by Theseus. In her prayer, Ariadne admonishes Zephyrus in front of his wife, angry at the west wind for assisting Theseus in his abandonment of her: "If Zephyros torments me, tell Iris the bride of Zephyros and mother of Pothos, to behold Ariadne maltreated" (Nonnus, Dionysiaca 47, 340).

Zephyrus and Iris had a son together, Pothos, one of the Erotes, a group of winged gods associated with love and sexual intercourse often depicted as part of Aphrodite's retinue. In a fragment of a poem by Alcaeus of Mytilene, it is suggested that Eros, the god of love and desire, was also a son of Zephyrus and Iris, although most other sources name Aphrodite and Ares as Eros' parents.

Zephyrus also fell in love with the nymph Chloris, whose devotion he won after vying for her affections with Boreas. Following this, he abducted and married her, and upon their wedding, she became the goddess of flowers, known as Flora in the Roman tradition. Chloris would bear Zephyrus a son, Karpos, whose name meant "fruit."

With the harpy Podarge, Zephyrus was the father of Balius and Xanthus, two immortal horses. The horses were given as a wedding gift to King Peleus during the celebrations of his marriage to the sea nymph Thetis. Peleus later gave the horses to his son, Achilles, who used them to draw his chariot during the Trojan War.

The horses performed well in battle, running with the winds' speed. Patroclus, Achilles' companion, would feed and groom them, and some said that only Patroclus could fully control the horses. In the Iliad, it is mentioned how, after Patroclus was killed, Balius and Xanthus stood motionless at the edge of the battle and wept. When a grief-stricken Achilles later blamed the horses for leaving Patroclus on the battlefield to die, the goddess Hera granted Xanthus the ability of speech so that he could tell the hero that it was not they but the god Apollo who allowed Patroclus to die. Xanthus then prophesized that Achilles' own demise was imminent:

We shall still keep you safe for this time, o hard Achilles. And yet the day of your death is near, but it is not we who are to blame, but a great god and powerful Destiny. For it was not because we were slow, because we were careless, but it was that high god, the child of lovely-haired Leto [Apollo], who killed him among the champions and gave the glory to Hektor [Hector]. But for us, we two could run with the blast of the West Wind [Zephryus] who they say is the lightest of all things; yet still for you there is destiny to be killed in force by a god and a mortal. (Homer, Iliad 19)

The Tale of Psyche

Zephyrus plays a prominent role in the tale of Eros and Psyche. Told in full by the Roman writer Apuleius in his 2nd-century CE novel The Golden Ass, the story describes how Psyche's beauty was so great that it incurred the jealousy of Aphrodite. Wishing to punish the girl, Aphrodite enlisted her son Eros (referred to by his Latin name of Cupid by Apuleius) to cause Psyche to fall in love with a horrible and hideous creature. As Eros went to carry out this task, he accidentally scratched himself with one of his own arrows, which famously caused their target to instantly fall in love. Naturally, this made him fall helplessly in love with Psyche.

Meanwhile, Psyche's parents had been unable to find her a husband despite her miraculous beauty. After consulting the oracle of Apollo, they were told that Psyche was destined to marry a hideous, serpentine creature that even the gods feared, and that they were to leave her standing atop a mountain to meet her fate. With heavy hearts, they agreed to the gods' demands and left their daughter alone on the mountaintop as instructed. After they left, Zephyrus carried the girl on his gentle wind to a hidden palace, which was the home of Eros. Refusing to let her look upon him, Eros visited Psyche only at night and left before the rising sun, and she soon fell in love with him.

However, Psyche quickly became lonely in the daytime and wished her sisters could visit her so they could see she was alive and unhurt. Eros relented and allowed Zephyrus to carry Psyche's two sisters on his wind to visit. Seeing the splendor of Psyche's new home, the sisters soon became jealous and convinced Psyche that she should look upon her husband's face, despite his wishes to the contrary. Against her better judgment, Psyche did so, causing Eros to abandon her.

Upon hearing this, the sisters rejoiced, believing that Eros would choose one of them to be his new wife. They traveled to the mountaintop where Zephyrus had previously carried them to Eros' palace and jumped from its peak, believing that the west wind would catch them. He did not, however, and Psyche's two sisters fell to their deaths and were dashed to pieces on the rocks below.

Later, after completing several impossible trials, Psyche was reconciled to Eros. They married and Psyche was made into a goddess by Zeus himself. Although Zephyrus only played a small role in their tale, it was undoubtedly an important one, for it was he who first brought the two lovers together. Apuleius does not give a reason for Zephyrus' aid to Eros, although it can perhaps be inferred that the two were connected through Zephyrus' son, Pothos, who was one of the Erotes like Eros himself.

The Story of Hyacinthus

Hyacinthus was a beautiful young man and the lover of the god Apollo. Although he had also been courted by Zephyrus, Boreas, and a mortal man named Thamyris, it was Apollo that Hyacinthus chose, much to the scorn of the others. Apollo doted on his lover, taking Hyacinthus with him on all of his fishing and hunting trips, teaching him how to play the lyre and shoot arrows. One day, Apollo was showing Hyacinthus how to play quoits, a game of discus throwing. After Apollo had taken one of the discuses and hurled it up in the air, an enthusiastic Hyacinthus ran to catch it. As he did, the discus hit the ground and rebounded, striking the youth on the forehead and knocking him to the ground.

Panicked, Apollo rushed over to find his lover bleeding from his wound, quite clearly dying. He tried all forms of healing and medicine known to him, but it was all to no avail, and Hyacinthus died. Grief-stricken, Apollo wished to die as well, but as a god this was impossible. From the patches of ground that had soaked in the youth's blood, Chloris, the flower goddess and Zephyrus' wife, caused flowers to grow with words of despair inscribed on the petals. The flower was thereafter known as the hyacinth, although it was different from modern flowers of that name.

In another version of this story, Hyacinthus' unfortunate death was no mere accident. In this version, Zephyrus, overcome with resentment that the youth had picked Apollo over himself, blew the discus from its course and caused it to strike and kill Hyacinthus. Centuries after the first telling of this story, English poet John Keats (l. 1795-1821) alluded to Zephyrus' murder of Hyacinthus in his poem Endymion through the eyes of onlookers at the quoits game:

Or they might watch the quoit-pitchers, intent

On either side, pitying the sad death

Of Hyacinthus, when the cruel breath

Of Zephyr slew him; Zephyr penitent,

Who now ere Phoebus mounts the firmament,

Fondles the flower amid the sobbing rain.(Bullfinch, 71)

This depiction of Zephyrus differs greatly from the other gentle, spring-bearing images of him. But this jealous side of the west wind was certainly remembered, for Nonnus, in the tenth book of his Dionysiaca recalls it almost as if in warning: "The death-bringing breath of Zephyros might blow again, as it did once before when the bitter blast killed a young man while it turned the hurtling quoit against Hyakinthos" (Dionysiaca 10, 253).

In the Iliad & Odyssey

Zephyrus also has roles to play in the two great Homeric epics. As told in the Iliad, Achilles could not get the funeral pyre for Patroclus to light. Standing away from the pyre, he lifted his voice and prayed to Zephyrus and Boreas, promising them splendid offerings if they could assist in lighting the pyre. The prayer was heard by Iris, who brought the message to her husband and his brother. Upon hearing Iris repeat Achilles's request, Zephyrus and Boreas immediately arose and, sweeping the clouds before them, lit a great flame upon Patroclus' pyre, which they did not let die down until the next morning.

In the Odyssey, Zephyrus plays a much more significant role. In the epic poem, Zephyrus and the other Anemoi reside on the Isle of Aeolus. Homer depicts Aeolus, the keeper of the winds, as a mortal man, although later, post-Homeric sources would paint him as a storm god. In the Odyssey, as well as in Virgil's Aeneid, the winds are subject to Aeolus.

Following his ordeal with the cyclops Polyphemus, the great hero Odysseus and his crew would make their way to Aeolus' island. Since the fall of Troy, Odysseus had been trying desperately to get back to his home in Ithaca and hoped that the keeper of the winds could assist him. Aeolus greeted Odysseus and his men warmly before entertaining them for an entire month, letting them stay in his palace with his family. On the last day, he gave Odysseus an ox-hide bag with a silver wire securing it shut. He explained that the bag contained all the winds except one, the west wind, which would provide Odysseus' ship with a gentle breeze that would carry him home to Ithaca. Should he encounter any danger, or otherwise have a need to alter his course, Odysseus need only to open the bag and release the wind he desired.

Odysseus departed the island and, true to Aeolus' word, was blown by Zephyrus across the sea and toward Ithaca. They came within sight of the city, close enough to see smoke rising from the chimneys when Odysseus, overcome with exhaustion and believing he had finally made it home, fell asleep. His men, who had not been made aware of what was contained in the ox-hide bag, had been waiting for this moment. Believing it to contain gold or wine, they untied it, releasing every wind that was trapped inside.

The release of all the winds at once blew the ship right back to Aeolus' island. Odysseus explained what had happened to the keeper of the winds, apologizing profusely and asking for more help. But Aeolus refused, realizing that Odysseus was opposed by the gods themselves. Aeolus told Odysseus that not one further breath of Zephyrus was to be given, before slamming the door in the hero's face. It would take Odysseus nearly ten years before he finally made it back home.

Conclusion

Although he was only a minor god, Zephyrus served a significant role in ancient Greek mythology. As the west wind and bringer of spring, he was looked upon favorably, with many anticipating his arrival. As seen with his assistance to Eros, Achilles, and Odysseus, he was willing to be helpful, but as the tale of Hyacinthus shows, he was also not one to be crossed. A powerful force of nature itself, Zephyrus and his brothers linger in the form of art, literature, and in the very winds themselves, long after their legends had first been told.