The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was among the most culturally significant of the early Chinese dynasties and the longest lasting of any in China's history, divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771-256 BCE). It followed the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE), and preceded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE, pronounced “chin”) which gave China its name.

Among the Shang concepts developed by the Zhou was the Mandate of Heaven – the belief in the monarch and ruling house as divinely appointed – which would inform Chinese politics for centuries afterwards and which the House of Zhou invoked to depose and replace the Shang.

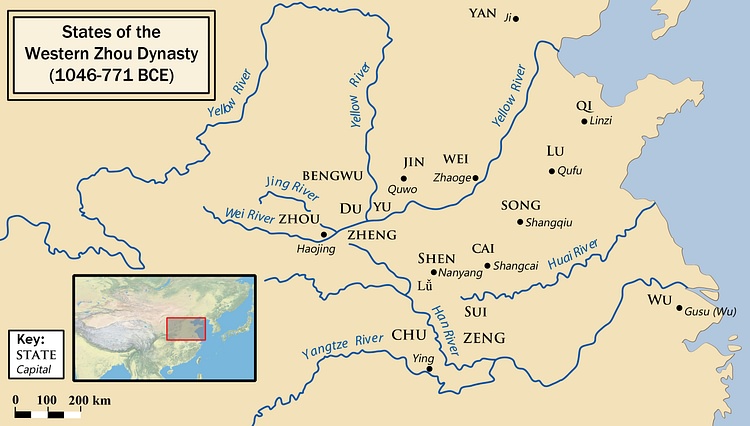

The Western Zhou period saw the rise of decentralized state with a social hierarchy corresponding to European feudalism in which land was owned by a noble, honor-bound to the king who had granted it, and was worked by peasants. Western Zhou fell just before the era known as the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 772-476 BCE), named for the state chronicles of the time (the Spring and Autumn Annals) and notable for its advances in music, poetry, and philosophy, especially the development of the Confucian, Taoist, Mohist, and Legalist schools of thought.

Eastern Zhou moved the capital to Luoyang and continued the Western Zhou model but with an ever-increasing breakdown of the imperial Chinese government which resulted in the claim that the Zhou had lost the Mandate of Heaven. The weakness of the king's position gave rise to the chaotic era known as the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) during which the seven separate states of China fought each other for supremacy. This period ended with the victory of the state of Qin over the others and the establishment of the Qin Dynasty which tried to erase the accomplishments of the Zhou in order to establish its own primacy.

The Zhou Dynasty made significant cultural contributions to agriculture, education, military organization, Chinese literature, music, philosophical schools of thought, and social stratification as well as political and religious innovations. The foundation for many of these developments had been laid by the Shang Dynasty but the form in which they came to be recognized is entirely credited to the Zhou.

The culture they established and maintained for almost 800 years enabled the development of the arts, metallurgy, and some of the most famous names in Chinese philosophy, among them Confucius, Mencius, Mo Ti, Lao-Tzu, and Sun-Tzu all of whom lived and wrote during the period known as the time of the Hundred Schools of Thought during which individual philosophers established their own schools. The contributions of the Zhou Dynasty provided the foundation for the development of Chinese culture by those that followed, most notably the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) which would fully recognize the value of the Zhou Dynasty's contributions.

Fall of the Shang & Rise of the Zhou

Prior to the Zhou was the Shang Dynasty who overthrew the Xia Dynasty (c. 2700-1600 BCE), claiming it had become tyrannical, and the Shang leader, Tang (dates unknown) then stabilized the region and initiated policies encouraging economic and cultural advances. The Shang made the most of the fertile soil on the banks of the Yellow River to produce abundant harvests, providing more food than required, the surplus of which then went toward trade. The resulting prosperity allowed for the development of cities, (some on a large scale, such as Erligang), arts, and culture.

The gods' approval of a king was evident in the prosperity of the land and the general well-being of the people. Any decline in either was interpreted as a sign the monarch had broken his contract with the gods and should be deposed. The last Shang emperor, Zhou (also given as Xin), became as tyrannical as the earlier Xia kings had been. He was challenged by King Wen of Zhou (l. 1152-1056 BCE) and was overthrown by Wen's second son, King Wu, who reigned 1046-1043 BCE as the first king of the Zhou Dynasty.

Western Zhou

King Wu at first followed the paradigm of the Shang in establishing a central government on either side of the Feng River known as Fenghao. Wu died shortly afterwards, and his brother, Dan, the Duke of Zhou (r. 1042-1035 BCE), took control of the government as regent for Wu's young son, Cheng (r. 1042-1021 BCE). The Duke of Zhou is a legendary character in Chinese history as a poet-warrior and author of the famous book of divination, the I-Ching. He expanded the territories eastward, and ruled respectfully, abdicating when the son of Wu came of age and took the throne as King Cheng of Zhou. Not every region under Zhou control admired their policies, however, and rebellions throughout the vast realm broke out, inspired by factions wishing to rule themselves.

A centralized government could not maintain the large territory that had been conquered and so the ruling house sent out trusted generals, family members, and other nobles to establish smaller states which would be loyal to the king. The policy of fengjian (“establishment”) was instituted which decentralized the government and allotted land to nobles who acknowledged the supremacy of the Zhou king. The fengjian policy established a feudal system and social hierarchy which ran, top to bottom:

- King

- Nobles

- Gentries

- Merchants

- Laborers

- Peasants

Each noble formed his own separate state with its own legal system, tax code, currency, and militia. They paid homage and taxes to the Zhou king and provided him with soldiers when necessary. In order to strengthen the king's position, the Mandate of Heaven concept was more fully developed. The king made sacrifices at the capital on behalf of the people and the people honored him with their loyalty and service.

The fengjian policy was so successful, producing such abundance of crops, that the resultant prosperity validated the Zhou as possessing the Mandate of Heaven. The wealth that was generated encouraged the so-called well-field system which divided lands between those cultivated for nobility and the king, and those worked by and for the peasantry. This was one of the few times in China's history that the upper and lower classes worked together for the greater common good.

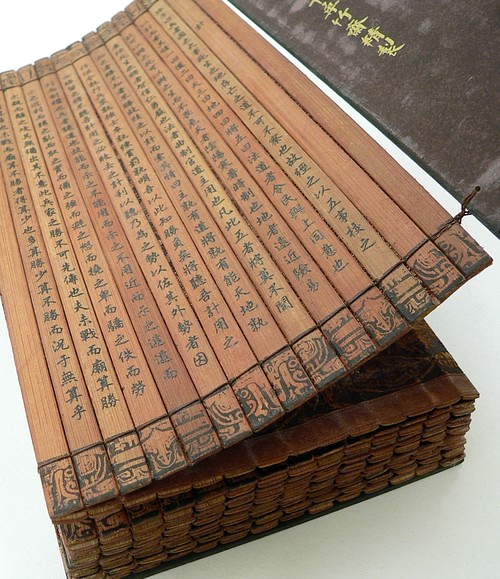

The Zhou culture, naturally, flourished with this kind of cooperation. Works in bronze became more sophisticated and the metallurgy of the Shang, overall, was improved upon. Chinese writing was codified and literature developed, as evidenced in the work known as Shijing (the Book of Songs, composed 11th-7th centuries BCE), one of the Five Classics of Chinese literature. The poems of the Shijing would have been sung at court and were thought to encourage virtuous behavior and compassion for members of all social classes.

This time of prosperity and relative peace, however, could not last. Scholar Patricia Buckley Ebrey comments:

The decentralized rule of the Western Zhou had from the beginning carried within it the danger that the regional lords would become so powerful that they would no longer respond to the commands of the king. As generations passed and ties of loyalty and kinship grew more distant, this indeed happened. In 771 BCE, the Zhou king was killed by an alliance [of tribesmen and vassals]. (38)

Western Zhou fell when invasions, most likely by the peoples known as the Xirong (or Rong), further destabilized the region. The nobility moved the capital to Luoyang in the east which gives the next period of Zhou history its name of Eastern Zhou.

Eastern Zhou

By all accounts, the era of Eastern Zhou was chaotic and violent but managed to produce literary, artistic, and philosophical works of startling originality and substance. The Spring and Autumn Period which begins the era of Eastern Zhou still retained some of the courtesy and decorum of the days of Western Zhou but that would not last for long. The separate states – Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Wei, Yan, and Zhao - all had more power than the Zhou at Luoyang at this time. Even so, it was still thought that the Zhou held the Mandate of Heaven and so each state tried to prove themselves the Zhou successor.

In the early years of the Spring and Autumn Period, chivalry in battle was still observed and all seven states used the same tactics resulting in a series of stalemates since, whenever one engaged with another in battle, neither could gain an advantage. In time, this repetition of seemingly endless, and completely futile, warfare became simply the way of life for the people of China during the era now referred to as the Warring States Period. The famous work The Art of War by Sun-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) was written during this time, recording precepts and tactics one could use to gain advantage over an opponent, win the war, and establish peace.

How widely read The Art of War was at this time is unknown but Sun-Tzu was not the only one who tried to end the violence through stratagems. The pacifist philosopher Mo Ti (also given as Mot Tzu, l. 470-291 BCE) went to each state, offering his knowledge in strengthening a city's defenses as well as offensive tactics in battle. His idea was to provide each state with exactly the same advantages, neutralizing all, in the hope that they would realize the futility of further warfare and declare peace. His plan failed, however, because each state, like a die-hard gambler, believed that their next offensive would result in the big win.

A Qin statesman named Shang Yang (d. 338 BCE), following Sun-Tzu's lead, advocated for total war, without regard to the old laws of chivalry, and stressed the goal of victory by any means at one's disposal. Shang Yang's philosophy was adopted by King Ying Zheng of Qin who embarked on a brutal campaign of carnage, defeated the other states, and established himself as Shi Huangdi, the first Chinese emperor. The Zhou Dynasty had fallen, and the Qin Dynasty now began its reign over China.

Zhou Contributions

The Qin would undo many of the advances of the Zhou but could not completely rewrite history. In the same way the Zhou had drawn on the accomplishments of the Shang, so the Qin did with the Zhou. The Zhou's advances in agriculture, for example, were kept and improved upon, notably irrigation techniques, dam building, and hydraulics which would be instrumental in Shi Huangdi's construction of the Grand Canal.

The use of cavalry and chariots in Chinese warfare (also originally Shang developments) were further developed by the Zhou and kept by the Qin. The Zhou had brought horsemanship to such a high level that it was considered a form of art and a requisite for the education of princes. Horses were thought so important, they were frequently buried with their masters or sacrificed for the spiritual power and protection their energy could provide to the deceased.

The most famous example of this is the tomb of Duke Jing of Qi (r. 547-490 BCE), found in Shandong Province in 1964 CE which, though still not fully excavated presently, is thought to contain the remains of 600 horses sacrificed to accompany the Duke into the afterlife. All of the states drew on the Zhou knowledge of horsemanship and Ying Zheng, in fact, made full use of the chariot and cavalry units developed by the Zhou in subduing the other states.

The Zhou separation of an army into units, deployed in different directions in battle, was also maintained by the Qin as was Zhou metallurgy. Shi Huangdi made the most of Zhou techniques in metalworking by forcing the subdued states to turn over their weapons which were melted down and turned into statues celebrating his reign.

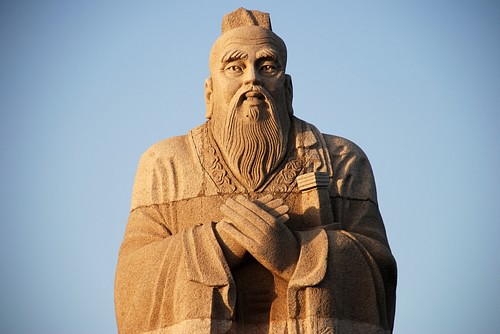

The Zhou contributions which were discarded by the Qin were all in the areas of art and culture. The Spring and Autumn Period and its time of the Hundred Schools of Thought had produced some of the most significant philosophical thinkers in the world. The major schools of thought were founded by Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE) whose famous Confucian precepts continue to inform Chinese culture, Lao-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) who codified and founded formal Taoism, and Han Feizi (l. c. 280-233 BCE), founder of the school of Legalism.

There were also many lesser known, but still significant, philosophers such as the sophist Teng Shih (l. c. 500 BCE), the hedonist Yang Zhu (l. 440-360 BCE), and the politician and philosopher Yan Ying (l. 578-500 BCE). Among the best-known later philosophers was the famous Mencius (also given as Mang-Tze, l. 372-289 BCE) who would codify the works of Confucius, and Xun Kuang (l. c. 310 - c. 235 BCE) whose work, Xunzi, reimagined Confucian ideals with a more pessimistic, pragmatic vision. Except for the legalism of Han Feizi, which the Qin adopted as its national policy, the work of all these philosophers was ordered destroyed; any which survived had been hidden by priests and intellectuals at the risk of their lives.

Zhou musical contributions were also undervalued by the Qin, though they were later recognized fully by the Han Dynasty. Central to the values of the Zhou Dynasty were the concepts of Li (ritual) and Yue (music and dance), commonly given as Li-Yue. Music was considered transformative, as explained by the scholar Johanna Liu:

Since the Zhou Dynasty, music has been considered as one important subject in the curriculum including four disciplines for cultivating the sons of royal family and eminent people from the State to be prominent future leaders. In the Book of Rites, it was said…'the direction of Music gave all honor to its four subjects of instruction, and arranged the lessons in them, following closely the poems, histories, ceremonies, and music of the former kings, in order to complete its scholars.' (Shen, 65)

Each piece of music had a corresponding dance and the combination of these was thought to not only improve the moral character of the individual but assist in balancing the nature of the cosmos. Confucius believed music to be essential in cultivating a good character, especially in a ruler, and that a lover of music would conduct himself, and his administration, justly.

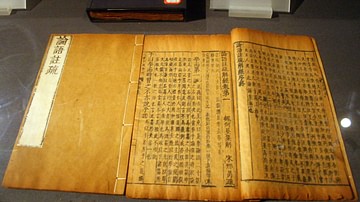

The Book of Rites referenced by Liu is one of the classic Chinese texts which was produced during the Zhou Dynasty during the period of the Hundred Schools of thought. The Four Books and Five Classics – which managed to survive the book burning of the Qin – became the standard texts for Chinese education. They are:

- The Book of Rites (also known as The Book of Great Learning)

- The Doctrine of the Mean

- The Analects of Confucius

- The Works of Mencius

- The I-Ching

- The Classics of Poetry

- The Classics of Rites

- The Classics of History

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

These works continue to be studied in the present day and for the same reason: they are thought to not only educate an individual but also elevate the soul and improve one's overall character.

Conclusion

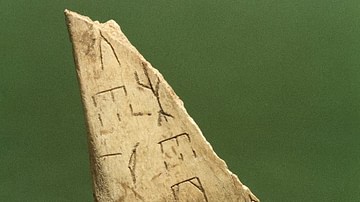

These works were only made possible by the Zhou development of writing. The Zhou developed the Shang script Jiaguwen into the Dashuan, Xiaozhuan, and Lishu scripts which would lend themselves to the development of still others. The Zhou's elevation of ancestor worship encouraged the development of religious thought and their vision of the Mandate of Heaven would continue to inform Chinese dynasties going forward for thousands of years.

If the Zhou had only produced philosophers such as Confucius and the others, it would be impressive enough, but they did far more. In the Western Zhou period, they established a decentralized, but cohesive, state which honored and inspired the people of all social classes, not just the noble and wealthy. They consistently improved upon what they had inherited from the Shang and looked for other ways to make their lives, and others', better.

In the Eastern Zhou period, even amidst the chaos of constant warfare, they continued to develop art, music, literature, and philosophy of the highest quality. The Zhou Dynasty's reign of nearly 800 years, in fact, was so profoundly influential at every level of culture that even the destructive policies of the Qin could not erase it. After the Qin fell to the Han Dynasty, the cultural contributions of the Zhou were revived and, today, are indistinguishable from Chinese culture.