The ruins of Zvartnots Cathedral are located on a flat plain within the Ararat Plateau between the cities of Yerevan and Etchmiadzin in Armenia's Armavir province near Zvartnots International Airport. Built in the middle of the 7th century CE, under the instructions of the Catholicos Nerses III (r. 641-661 CE), Zvartnots is the oldest and largest aisled tetraconch church in historical Armenia. Its design strongly influenced later constructions of other Armenian churches with central-domed cross-halls, leaving an enduring architectural and artistic mark in what is present-day Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and eastern Turkey. Although largely destroyed in an earthquake in the 10th century CE, Zvartnots Cathedral was excavated and rediscovered between 1900-1907 CE. It was partially reconstructed in the 1940s CE - based on the research of the Armenian architectural historian Toros Toramanian (1864-1934 CE) - and Zvartnots' ruins can be visited today. UNESCO added the ruins of Zvartnots Cathedral to its World Heritage List in 2000 CE.

Background History

Zvartnots Cathedral was constructed at a time of much chaos in Near East. After decades of intermittent warfare between the Sasanians and Byzantines, Arab invaders carrying the Islamic faith had surged out of the Arabian Peninsula, taking control of Jerusalem and Alexandria from the Byzantines, and vanquishing the formidable Sasanian Empire in what is now Iraq and Iran. As Armenia lies in the Caucasus and functioned as a geographical bulwark on the Byzantine Empire's eastern frontier, it quickly became a contested region between the Arabs and Byzantines. The first Arab invasion of Armenia occurred in 640 CE, and the Arabs massacred thousands of Armenians at the ancient capital of Dvin in 642 CE. From 643-656 CE, the Arabs launched a full-scale invasion of the Caucasus only to be halted temporarily by the armies of the Byzantine Emperor Constans II (r. 641-668 CE). While many Armenians were grateful for Byzantine aid, many were worried about increasing religious influence and interference from Byzantium.

Armenians were divided in the 7th century CE between those who wished for the Armenian Apostolic Church to accept decisions made at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE, which condemned the belief of one incarnate nature of Christ, and those who did not and wished to maintain the separation between the Eastern Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic Churches. Things became more divisive when due to the presence of Byzantine troops on Armenian soil, the Armenian Apostolic Church was placed under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople in 647 CE by Constans II. (This was subsequently rejected by an Armenian Apostolic Church council a year later.) Nerses III “the Builder” had been elected as the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church in 640 CE just as the Arab armies arrived in Armenia. During this era, the Armenian Catholicos - the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church - held both temporal and spiritual power over the Armenian people, and so Nerses III exercised and wielded considerable political might.

Constans II visited Nerses III in Armenia in 652 CE in order to expand Byzantine influence in matters concerning religion as well as in the development a mutual, common defense against the Muslim Arabs. Nerses III was pro-Byzantine in both his religious and political views; he was fluent in Greek, served in the Byzantine army, and even visited Constans II's court in Constantinople in 654 CE. Constans II found Nerses III to be a most useful and much-needed ally due to his fear of further Arab invasions as well as potential clashes between Byzantine and Armenian soldiers over their religious differences.

Architectural Details & Artistic Elements

According to the History of Heraclius, widely attributed to the Armenian bishop Sebeos (fl. 7th century CE), the construction of Zvartnots Cathedral began c. 645 CE and continued with occasional interruptions due to Arab razzias into the 650s CE. Armenian legends hold that Constans II was in attendance at Zvartnots' consecration, but there is no historical evidence of this. Sebeos attests that Zvartnots Cathedral was built “to the glory of God.” “Zvartnots” means “heavenly host” in Armenian, which in turn might be a pun derived from the Greek “egregoros,” which means translates as “powers of angels” or heavenly host.” Some scholars contend that the Armenian root word “Zawr” relates to the military and that “Zvartnots” could even be translated as “celestial militia.” The church was designed for congregational worship, but there is a consensus among historians that Nerses III intended Zvartnots Cathedral to be a monument to Armenian-Byzantine ties in addition to functioning as a projection of his own power as an intermediary between Byzantium and Armenia. (It should be noted that Nerses III was also responsible for the construction of the St. Gevorg Chapel at Khor Virap Monastery — this structure lies 47 km (29 mi) southeast of Zvartnots Cathedral — which was constructed at the same time.)

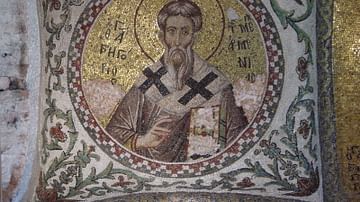

Nerses III built his church on the site where it was believed according to local tradition that St. Gregory “the Illuminator” (c. 257 – c. 331) converted King Tiridates III of Armenia (r. 287–330 CE) to Christianity. Its design as an aisled tetraconch church recalls similar structures across the Roman Mediterranean in what is now Italy (San Lorenzo in Milan), Egypt (Abu Mena), and Syria (Bosra, Rusafah, and Apamaea). Of those, Zvartnots Cathedral resembles most the structures from Syria, which date from the second half of the 5th century CE.

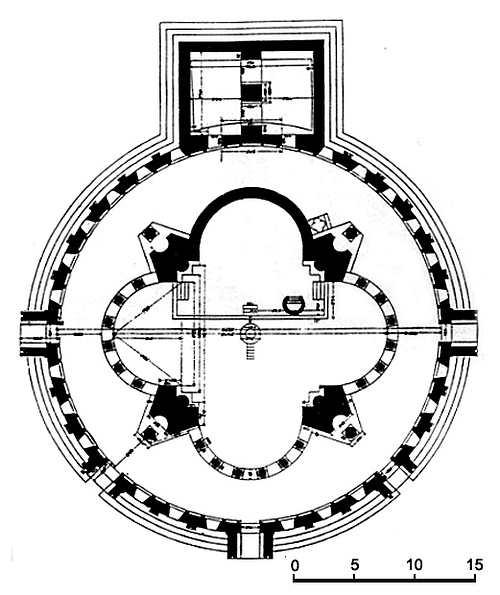

Zvartnots was constructed largely from basalt quarried nearby, along with tufa, pumice, and obsidian. The cathedral contained four W-shaped piers to support its large dome, which in turn divided the cathedral's interior and exterior spaces. Zvartnots' dome reached a height of about 45 m (148 ft), and the entire structure of the cathedral sits on a stone platform that is 5 m (16 ft) tall. The cathedral's core was dominated by a circular ambulatory and a large chamber with an unknown function. There once existed an ambo to the southeast of the cathedral apse as well. The cathedral was sumptuously ornamented with mosaics and well furnished. From the ruins, scholars have deduced that the cathedral's exterior was richly decorated with carvings of pomegranates, grapevines, as well as figural ornaments and graced blind arcades. Nerses III built a small palace for himself directly adjacent to Zvartnots with elegant colonnaded porches.

Unlike earlier Armenian churches or religious structures, Zvartnots contains columns with Ionic capitals, which were not common in Armenian architecture in the 7th century CE. Columnar exedrae placed between the piers of the cathedral contained Nerses III's personal monograms in Greek rather than Armenian. Capitals with monograms or personal devices were virtually unknown in ancient Armenia, but they were common throughout the Roman and Byzantine Empires with the best examples being those of the Emperor Justinian (r. 527-565 CE) and Empress Theodora (c. 500-548 CE) at the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Four column capitals decorated with eagles once stood in front of the cathedral's four main piers, facing the ambulatory. The eagle with outstretched wings was a potent symbol of imperial Byzantine power. A unique sundial with an Armenian inscription found by archaeologists likely occupied a position somewhere on the southern façade of the cathedral; additionally, a Urartian stele found within the premises of the cathedral was likely reused either for decor or for some structural purpose.

Artistic Legacy & Rediscovery

Zvartnots Cathedral provided the architectural blueprint for many fine churches throughout the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia, including a ruined church in Bana, Turkey; a ruined Armenian church in Lekit, Azerbaijan; and the Church of St. Gregory in Ani, Turkey. The modern Holy Trinity Church in Yerevan, Armenia is also modeled on Zvartnots Cathedral. Historians believe that Zvartnots Cathedral collapsed following an earthquake in the 10th century CE. It was largely forgotten until it was excavated in 1900-1901 CE.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.