An amphitheatre was a structure built throughout the Roman empire where ordinary people could watch such spectacles as gladiator games, mock naval battles, wild animal hunts, and public executions. Usually oval in form, the largest examples could seat tens of thousands of people, and they became a focal point of Roman society and the lucrative entertainment business. Amphitheatres are one of the best surviving examples of ancient Roman architecture, and many are still in use today, hosting events ranging from gladiator re-enactments to opera concerts.

Architectural Features

The fully enclosed amphitheatre was a particular favourite of the Romans and evolved from the two-sided stadiums and semicircular theatres of ancient Greece. The date and location of the first true amphitheatre are unknown, but the tradition of gladiator fights had roots in the Etruscan and Osco-Samnite cultures. The earliest securely dated amphitheatre is that of Pompeii, built c. 75 BCE and known as the spectacula. Early structures took advantage of rock and earth hillsides to build the banks of wooden seating on, but by the 1st century BCE free-standing stone versions were being constructed. Amphitheatres of all sizes were built across the empire as Roman culture swept in the path of its army. Indeed, army camps often had their own dedicated arena, usually built using timber and used for training as well as entertainments. Amphitheatres were made oval or elliptical so that the action would not remain stuck in one corner and to offer a good view from any seat in the house.

The Colosseum, officially opened in 80 CE and known to the Romans as the Flavian Amphitheatre, is the largest and most famous example with a capacity of at least 50,000 spectators. Dwarfing all other buildings in the city, it was 45 metres high and measured 189 x 156 metres across. It had up to 80 entrances, and the sanded arena itself measured a massive 87.5 m by 54.8 m. On the upper storey platform, sailors were employed to manage the large awning (velarium) which protected the spectators from rain or provided shade on hot days.

The Colosseum's design became famous as it was placed on coins so that even people who had never been in person knew of Rome's greatest temple to entertainment. The design was copied throughout the empire: a highly decorative exterior, multiple entrances, seating (cavea) set over a network of barrel vaults, a wall protecting spectators from the action of the arena (sometimes with nets added), and underground rooms below the arena floor to hide people, animals, and props until they were needed in the spectacles. There was also an extensive drainage system, a feature seen at other arenas such as Verona's amphitheatre where it still functions and has greatly contributed to the excellent preservation of the monument.

The Arena of Verona measures 152 x 123 metres and was third biggest after the Colosseum and Capua. It is another excellent example of the features involved in a Roman amphitheatre. It was constructed in the 1st century CE, using a cement and rubble mix known as opus caementicum, brick, and stone blocks set in square pillars to create an external façade of three levels of 72 arches, each spanning 2 metres and creating a total height of over 30 metres. The lowest arches lead directly to an interior corridor 4.4 metres wide, which runs around the Arena. From this corridor, steps lead upwards at regular intervals and on four different levels to form vomitoria (exits), which give access to the interior cavea. Inside, the seats were arranged in four elliptic rings giving a total of 44 rows of seating.

The Romans built over 200 amphitheatres across the empire, most of them in the west as in the east very often existing Greek theatres and stadiums were converted/employed for public spectacles. Other well-preserved arenas besides the Colosseum and the Arena of Verona which can be visited today include Arles, Burnum, Capua, El Djem, Frejus, Nimes, Leptis Magna, Pergamon, Pompeii, Pula, Salona, Tarragona, and Uthina.

The Events

If there was one thing the Roman people loved it was spectacle and the chance to escape reality for a few hours and gawk at the weird and wonderful public shows which assaulted the senses and ratcheted up the emotions. Roman rulers knew this well, and so to increase their popularity and prestige with the people, they put on lavish and truly spectacular shows, which cost fortunes and lasted all day for several days. The whole live entertainment industry thus became a huge source of employment, from horse trainers to animal trappers, musicians to sand rakers.

To modern eyes, the bloody spectacles put on by the Romans can cause revulsion, but perhaps we should consider that the sometimes shocking events of these spectacles were a form of escapism, just as cinema and computer games are today, rather than representative of social norms and barometers of accepted behaviour in the Roman world. Perhaps the shockingly different world of Roman spectacle, in fact, helped reinforce social norms rather than acted as a subversion of them.

Emperor Augustus established rules so that slaves and free persons, children and adults, rich and poor, soldiers and civilians, single and married men were all seated separately, as were men from women. Naturally, the front row with more comfortable seats in amphitheatres was reserved for the local senatorial class. Tickets were probably free to most forms of spectacle, as organisers, whether city magistrates given the responsibility of providing public civic events, super-rich citizens, or the emperors who would later monopolise control of spectacles, were all keen to display their generosity rather than use the events as a source of revenue.

Gladiator Fights

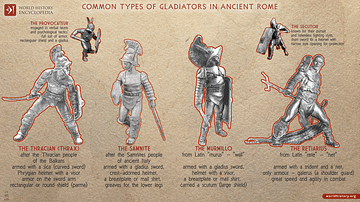

In the bloody events of the arena, none came more graphic than the one-on-one gladiator fights. Qualities such as courage, fear, technical skill, celebrity, and, of course, life and death itself, engaged audiences like no other entertainment, and no doubt one of the great appeals of gladiator events, as with modern professional sport, was the potential for upsets and underdogs to win the day.

In Rome, city magistrates had to put on a gladiator show (munera) as the price for winning office, and cities across the empire offered to host local contests to show their solidarity with the ways of Rome and to celebrate notable events such as an imperial visit or an emperor's birthday. Gladiator fights became hugely popular, and those who went on a winning streak became living legends, darlings of the crowds who even had their own fan clubs.

Wild Animal Hunts

Besides gladiator contests, Roman arenas hosted events using exotic animals (venationes) captured from far-flung parts of the empire such as rhinos, panthers, and giraffes. These were made to fight each other or humans. Animals were frequently chained together, often a duo of carnivore and herbivore, and cajoled into fighting each other by the animal handlers (bestiarii). Certain animals acquired names and gained fame in their own right as did their human 'hunters' (venatores). During these events, the underground mechanisms were employed to have animals appear unexpectedly in the arena, which was often landscaped with rocks and trees to resemble exotic locations and heighten the realism.

Mock Naval Battles

Shows in the arena often accompanied the lavish festivities held during a Roman triumph, and one of the most popular events was to audaciously restage real naval battles (naumachiae), naturally, in as lifelike and deadly fashion as possible. Julius Caesar commemorated the Alexandrian war by staging a huge battle between Egyptian and Phoenician ships while Augustus staged one to celebrate his victory over Mark Anthony at Actium. Nero went one better and flooded an entire amphitheatre to host his naval battle show. These events became so popular the later emperors did not need the excuse of a military victory to wow the public with epic mythologically-themed sea battles. The manoeuvres and choreography of these events were invented but the fighting was real, and so condemned prisoners and prisoners of war gave their lives to achieve ultimate realism for the baying crowd.

A Gallery of 12 Roman Amphitheatres

Public Executions

Arenas also hosted the execution of criminals – usually during the lunchtime lull – which was achieved in imaginatively gruesome ways like setting wild animals on the condemned (damnatio ad bestias) or making them fight well-armed and well-trained gladiators or even each other. Other more theatrical methods included burning at the stake or crucifixion, often with the prisoner dressed up as a character from mythology to give a little extra colour to the occasion. The spectators were not passive viewers as sometimes an execution was cancelled if the crowd demanded it.

Decline & Reuse

Eventually, gladiator contests, at odds with the new Christian-minded Empire, declined under the later emperors and finally came to an end in 404 CE. The spectacle of criminals fighting animals went on for another century, but gradually the amphitheatres crumbled into disuse and suffered varying degrees of reuse and abuse. The tale of the Colosseum is a common fate: made into a fortress in the 12th century CE, damaged by an earthquake in the 13th century CE, and used as a public quarry by Pope Alexander VI. Still, the Colosseum and many other surviving Roman arenas remain today magnificent monuments and enduring testimony to both the skills and the vices of the Roman world. Many amphitheatres are actually still in use and still host large crowds for all manner of cultural events such as the world-famous summer opera season in Verona, mock gladiator fights in Tarragona, and rock concerts at Arles.