Antinous (l. c. 110-130 CE) was a youth of Bithynia who became the beloved of the Roman emperor Hadrian (l. 76-138 CE, r. 117-138 CE) from around the age of 13 until his death at nearly 20. His year of birth is unknown as are any details of his life before he met Hadrian in 123 CE.

All the ancient sources agree he was almost 20 when he drowned in the Nile River while accompanying Hadrian on a tour of Egypt in October 130 CE and so his birth year is generally accepted as 110 or 111 CE and his birthday as 27 November. After his death, Hadrian had him deified and built the city of Antinopolis in his honor on the shore of the Nile. A cult soon formed around the new god, who was associated with the Egyptian deity Osiris, which spread quickly and became quite popular. Antinous was almost instantly revered as a dying-and-reviving god, a deity who dies and returns to life for the good of humanity. Some sort of personal salvation was involved in the beliefs of the cult which spread quickly from Egypt throughout the provinces of the Roman Empire.

The cult was still popular in the 4th century CE, rivaling the new religion of Christianity. Pagan writers objected to the cult on the grounds that there was no evidence of Antinous’ divinity while Christian writers condemned it on the grounds of promoting immorality. The cult remained active, however, until it was outlawed along with the other pagan belief systems under Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) in 391 CE. The cult has been revived in the modern day by the gay community who embrace Antinous as a symbol of empowerment and personal healing.

Meeting with Hadrian

Antinous was born in the city of Claudiopolis in Bithynia, Asia Minor (modern-day northwest Turkey). It is assumed that he came from an upper-class family because, although there are no ancient sources recording his first meeting with Hadrian, he must have been part of some socially respectable group welcoming the emperor. Scholar Anthony Everitt comments:

Rulers do not happen upon strangers in the street, and we must assume that Antinous was taking part in some public ceremony when he was noticed. This could well have occurred at Claudiopolis, but, if not, then at the capital, Nicomedia. Heraclea offers a third possibility, for games were founded and held there in the emperor’s honor and Antinous could have been a competitor…A late reference to Antinous as Hadrian’s "slave" can be discounted, for that would have been seen as a thoroughly disreputable provenance for an imperial favorite. (238)

Hadrian was in Bithynia in 123 CE as part of a tour of the provinces and included Nicomedia as one of his stops because it had recently suffered significant damage from an earthquake and Hadrian had sent funds for relief and restoration. In keeping with his usual policy of overseeing projects personally, he wanted to see how the work had been completed. This argues for Nicomedia as the site of his first meeting with Antinous. Whether he was part of a welcoming committee or a participant in celebratory games, the young man caught the emperor’s eye. Everitt elaborates:

Whatever the details of the boy’s origins and social status, the large, the overwhelming fact is that Hadrian fell in love with Antinous. The relationship was to color the rest of their lives. But what did "falling in love", and for that matter in lust, mean for an elite citizen in the Roman empire? Something very different from our ideas today. Sex did not have the attributes of sin and guilt that Christianity brought to it. Most people in the ancient world found making love to be, in principle, an innocent, or at least an innocuous, pleasure. (239)

Hadrian added Antinous to his retinue and then sent the youth to Rome to be educated at the boarding school known as the Paedogogium. This school focused on training boys between the ages of 12-18 in service at the imperial court. Students learned practical skills such as bookkeeping and hairdressing as well as the arts of entertainment including juggling and dancing. Graduates became the valued servants of senators and other members of the upper-class at Rome and in the provinces.

Hadrian’s Sexuality

Hadrian was a highly cultured and literate man who had been taken under care by the future emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) in 86 CE after his father died when he was ten years old. Although he was born in Italica (modern-day southern Spain), his early love for Greek literature and culture drew him to Greece, the country he is most often associated with. Trajan’s wife Plotina arranged Hadrian’s marriage to Trajan’s grandniece Vibia Sabina (l. 83 - c. 137 CE) but the union was not a happy one. There is little evidence that Hadrian was sexually attracted to women but much that makes clear he favored men.

The Romans adopted a liberal attitude toward sexual behavior and viewed relationships between older and younger men as another mode of sexual expression, no better or worse than another, as long as both parties consented to the liaison. Hadrian had taken male lovers in the past and modeled these relationships on that of the Greek understanding of an erastes (lover) and an eromenos (beloved) with the lover almost always being older and established in society and the beloved younger and just entering the adult sphere, often between 13-18 years old.

Although there was a sexual aspect to the relationship, this was considered secondary to a friendship (a philia) based on mutual respect. Homosexuality and homosexual behavior were understood as a legitimate option to heterosexuality and, in fact, there were no terms in Latin to distinguish between the two. Everitt writes:

Men did not categorize themselves as homosexual, for, until the inventions of modern psychology, there was no concept, and so no term, for man-to-man sexual preference as a viable and exclusive alternative to heterosexuality and as a describer of personality…Romans were quite capable of telling straights from gays even without our words for them [and] many slept impartially with members of both sexes. (241-242)

Hadrian viewed Antinous as his beloved in the Greek sense, as someone to educate – formally, socially, and sexually – as well as to lavish gifts upon. Part of this education included travel and Hadrian took Antinous with him whenever he left Rome after 125 CE.

Travels with Hadrian

It is unclear how long Antinous attended the school in Rome but, by 125 CE, he was living with Hadrian at the emperor’s villa at Tibur (Tivoli) outside the city. The villa was a lavish retreat of gardens, reflecting pools, waterfalls, and fountains on the terraced top of a hill. The villa itself had bedrooms and banquet halls and suites, mosaic-tiled floors, frescoes, and heated baths and was staffed by a small army of servants, slaves, cooks, waiters, butlers, and maids. There was also a stable of horses and a staff of guides and aides for hunting, Hadrian’s favorite pastime.

In 127 CE, Hadrian traveled through Italy, probably with Antinous, and at this time fell ill with some lingering sickness which the doctors of his day could not define and is still unknown in the present. Whatever the affliction was, it plagued him through late 130 CE. His illness does not seem to have slowed him down, however, and the fall of 128 CE found him in Greece attending the Eleusinian Mysteries with Antinous. Hadrian was completely initiated into the mysteries at this time and Antinous with him.

From Greece, the couple traveled to Judaea and Syria and then down to Egypt, arriving in August of 130 CE. Hadrian had a long-standing interest in Egyptian rites and magic, and it is possible he was seeking a cure for whatever had been ailing him. If so, there is no evidence of this in his activities upon arrival. He and Antinous visited the grave of Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE) and the sarcophagus of Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) before going to the Canopic canal area near the ports, known for its "places of revelry" and all-night parties. The couple also hunted together in Egypt and, at one point, Hadrian wounded a lion which charged Antinous before it was killed by the emperor. After their hunting expeditions and parties, they set off with their retinue for a trip up the Nile River.

Death in Egypt

The party stopped at Heliopolis where Hadrian conferred with a priest named Pachrates who prepared a potion and seems to have performed a ritual which brings sickness to the person or people one specifies. It is possible the spell could also remove illness and that Hadrian was seeking a cure for his own, but this is speculation. They moved on from Heliopolis to Hermopolis where they visited the Sanctuary of Thoth and prepared for the festival of Osiris which celebrated the death and rebirth of the god and the fertility this brought to the land. On 22 October 130 CE, they took part in the Festival of the Nile, and shortly after that, Antinous’ corpse was found floating in the river.

That he drowned was obvious, and Hadrian, in his account of the incident, says it was an accident without elaborating. Everitt cites the three ancient sources on Antinous’ death which claim otherwise – Cassius Dio (l. c. 155 - c. 235 CE), the Historia Augusta (a Roman history dated to c. 4th century CE), and Aurelius Victor (l. c. 320 - c. 390 CE) – who claim Antinous sacrificed himself (or was sacrificed) to cure Hadrian of his illness. Cassius Dio writes:

Antinous…had been a favorite of the emperor and had died in Egypt, either by falling into the Nile, as Hadrian writes, or, as the truth is, by being offered in sacrifice. For Hadrian, as I have stated, was always very curious and employed divinations and incantations of all kinds. (Everitt, 288)

Aurelius Victor agrees:

When Hadrian wanted to prolong his life, and magicians had demanded a volunteer in his place, they report that, although everyone else refused, Antinous offered himself. (Everitt, 288)

The Historia Augusta includes the passage:

Concerning this incident there are varying rumors; for some claim that he [Antinous] had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others – what both his beauty and Hadrian’s excessive sensuality indicate. (Everitt, 288)

As Everitt points out, it is unlikely that Antinous’ death was an accident because he was the most notable member of the party after Hadrian himself and would no doubt have been attended to prevent just this sort of thing from happening. The Historia Augusta passage suggests that Antinous committed suicide because he was no longer a youth at the age of 20 and feared Hadrian would cast him aside for someone younger. Scholars regularly dismiss this claim as there is nothing in the other ancient sources to suggest Hadrian would do this, while his grief over Antinous’ death – which ancient writers note was excessive – makes clear his deep and constant feelings for the younger man.

It is possible, of course, that Hadrian is telling the truth and Antinous slipped into the river and drowned. It is also possible, however, that he sacrificed himself in a ritual whereby he surrendered his spirit to save his lover. It was believed that anyone who drowned in the Nile – except for suicides – became a god because the river, which gave the land life, had taken that person for a specific purpose and greater good. Perhaps, in a ritual learned from Pachrates at Heliopolis, Antinous believed he was surrendering his mortal life so Hadrian could live pain-free while he himself would be rewarded with the elevated life of a god. This would not have been considered suicide but, instead, ritual sacrifice. Whether as a result of this sacrifice or by coincidence, Hadrian’s health improved afterwards.

Deification & the Cult

There is no way of knowing for sure what happened or how Antinous drowned but it is clear that, whatever awaited him in the afterlife, he became a god to those he left behind and many others not yet born. Within a week of his drowning, Hadrian ordered a city built across from Hermopolis in his honor – Antinopolis – which was patterned on the layout of Alexandria. As at Alexandria, where Alexander the Great still lay in state, Antinous would be interred at this city but, in what seems a last-minute decision, Hadrian brought the corpse back to his villa at Tibur where Antinous was laid to rest in a grand tomb. The city was built, however, and no expense was spared.

Antinous is thought to have drowned on the day of the Festival of Osiris, linking him with the god, and was now known as Antinous-Osiris or Osirantinous. From his city in Egypt, worship of the new god spread to Greece, Rome, and throughout the provinces of North Africa, Asia Minor, and as far, finally, as Britannia. Everitt writes:

Antinous had a marvelous life after death. His cult spread with great speed and his popularity grew with the years. As a god who dies and is resurrected, he even became a rival to Christianity for a while; it was claimed that "the honor paid to him falls little short of that which we render to Jesus." (292)

Throughout the Mediterranean region, the cult spread so quickly that temples, ceremonial games, shrines, and altars were established – and had become popular pilgrimage sites – only a few years after his death. One aspect of his cult which strongly suggests that he sacrificed himself for Hadrian is that he was regarded as a healing deity so powerful he could ward off the most serious diseases and cure even terminal patients.

He was not regarded as divine by all, however, as adherents of other, long-established, cults felt threatened by the new one and claimed he was a hero, a divine hero, or a demigod but not fully divine. Even with these stipulations, however, he was still recognized as a powerful, immortal, entity who, having once been human himself, felt pity for mortals and exerted more effort to help them than the immortal gods who had existed solely as divinities for millennia.

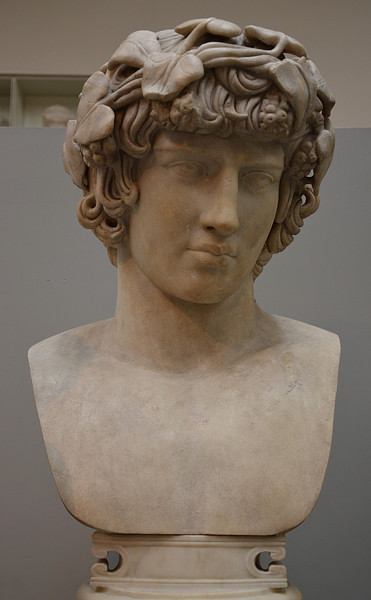

Oracles at Antinous’ sacred sites answered peoples’ questions and provided advice, but how he was worshipped is unknown because the practices were lost after Theodosius I banned all pagan religions in 391 CE. It is thought that adherents brought sacrifices to the temples – all of which seem to have had one or more of the over 2,000 statues of Antinous as a focal point – and that priests cared for these statues daily just as in other cults. The statue would have been offered food and drink every day and would be bathed and anointed with oil. To date, 115 statues of Antinous have been found at various sites along with coins bearing his image and inscription. Some of these coins were issued as currency but others were amulets or medallions, most likely received by adherents at temples and shrines, which were carried to ward off disease, misfortune, and remind one of Antinous’ love and compassion.

Conclusion

Not everyone was interested in Antinous’ love, however. Even before the cult was banned, Christians were destroying temples and pulling down statues of Antinous in the belief that he was an affront to their faith. Jesus Christ was also seen as a dying-and-reviving god, and the cult of Antinous was too popular and powerful a rival to allow for another version of this deity. The cult would have been regarded as especially dangerous as the deified Antinous, like Jesus, had also once been mortal and ministered to his followers with the same degree of compassion for what they suffered in the flesh. By the end of the 5th century CE, the cult was gone but some statues of Antinous remained, re-erected, possibly, by people who had no memory of who he had been or by those who kept the faith alive in secret. Everitt writes:

Even today, his is the most instantly recognizable and memorable face from the classical world. Antinous is one of the very few ancient Greeks and Romans to have his own active websites. (294)

In the modern day, he has been embraced by the gay community as The Gay God, invoked for protection, healing, and personal salvation. The website Temple of Antinous clarifies the vision of the new adherents of the faith:

Hadrian deified Antinous because he loved him, because he wanted to give Antinous everything he had within his power to bestow upon Antinous. Hadrian inaugurated the ancient religion of Antinous as a way of asking other gay men to remember Antinous and ensure that his name would never be forgotten and that his beauty and gentle heart would never fade away…This is the deepest foundation of the Modern Religion of Antinous…to hear the call of Hadrian across the centuries, to love, worship, and care for the memory of the beautiful Antinous. (1)

Like the ancient cult, the modern religion focuses on love, self-empowerment, and healing emotionally, spiritually, and physically through devotion to the god and service to others. The modern faith also mirrors the ancient in that it has grown increasingly popular in the past decades and no doubt will only continue to do so.