The Nimrud Dogs, five canine figurines found at the ancient Mesopotamian city of Nimrud, were only a few of the many startling finds in the region during the 19th century when expeditions were sent to corroborate biblical narratives through physical evidence and wound up doing precisely the opposite.

In 612 BCE the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell to the invading forces of Babylonians, Persians, Medes, and Scythians. The empire had been expanding in every direction since the reign of Adad Nirari II (c. 912-891 BCE) and grew more powerful under great kings such as Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 BCE), Shalmaneser V (727-722 BCE), Sargon II (722-705 BCE), Sennacherib (705-681 BCE), and Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) until, by the time of Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE), it had grown too large to manage effectively.

Ashurbanipal was the last of the Assyrian kings who had the personal power and skill to manage an empire, and after he died the vassal states recognized their chance to free themselves. The many regions which had been held so tightly under Assyrian control seized on the weakness of the fracturing empire and, banding together, marched to destroy it.

All of the great Assyrian cities, many of which had endured for millennia, were sacked and their treasures carried off, destroyed, or discarded at the various sites. The Assyrians had held the region under such a tight grip that, once it was loosened, the former subject-states knew no restraint in venting their frustrations and seeking revenge for past injustices. Great cities such as Nineveh, Kalhu, and Ashur were sacked, with Nineveh so thoroughly destroyed that future generations could not even tell where it had been.

Excavations & Discovery

At Kalhu, site of one of the former capitals of the empire, the sands of Mesopotamia gradually covered the ruins, and the city probably would have been forgotten were it not for the prominent mention of Mesopotamian cities such as Babylon and Nineveh in the Bible. In the 19th century, European explorers, seeking historical evidence for biblical narratives, descended upon Mesopotamia and recovered these lost cities. Among these was Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894) who was the first to systematically excavate Kalhu, afterwards known as Nimrud.

Layard and the others were sponsored by European organizations and museums who hoped their efforts would uncover physical evidence proving the historical accuracy of the Bible, specifically the books of the Old Testament. These expeditions, however, had a completely different effect than what was intended. Prior to the mid-19th century, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and the narratives thought to be original works; the archaeologists discovered that contrary to this belief Mesopotamia had created narratives of the Great Flood and the Fall of Man centuries before any of the biblical books were written.

These discoveries increased European interest in the region, and more archaeologists and scholars were sent. When Layard began his work at Kalhu, he did not even know which city he was excavating. He believed he had discovered Nineveh and, in fact, published his bestselling book on the excavation, Nineveh and its Remains, in 1849, still confident of his conclusions. His book was so popular and the artifacts he uncovered so intriguing that further expeditions to the region were quickly funded. Further work in the region established that the ruins Layard had uncovered were not those of Nineveh but of Kalhu, which the scholars of the time associated with the biblical Nimrud, the name the site has been known by ever since.

The Nimrud Ivories

Layard's work was continued by William K. Loftus (1820-1858) who discovered the famous Nimrud Ivories (also known as the Loftus Ivories). These incredible works of art had been thrown down a well by the invading forces and perfectly preserved by the mud and earth which covered them. Historian and curator Joan Lines of the Metropolitan Museum of Art describes these pieces:

The most striking objects from Nimrud are the ivories - exquisitely carved heads that once must have ornamented furniture in the royal palaces; boxes inlaid with gold and decorated with processions of small figures; decorative plaques; delicately carved small animals. (234)

The discovery of the ivories suggested there could be even greater finds buried in the former wells, crypts, and ruined buildings of the cities and further expeditions to Mesopotamia were funded. Throughout the rest of the 19th and into the 20th century, archeologists from all over the world worked the sites of the region, uncovering the ancient cities and retrieving artifacts from the sands.

In 1951-1952, the archaeologist (and husband of mystery writer Agatha Christie) Max Mallowan (1904-1978) came to Nimrud and discovered even more ivories than Loftus had. Mallowan's discoveries, in fact, are among the most recognizable from museum exhibits and photographs. The ivories are routinely cited, naturally, as Mallowan's greatest find at Nimrud, but a lesser-known discovery is of equal importance: the Nimrud Dogs.

Dogs & Magic

Dogs featured prominently in the everyday life of the Mesopotamians. The historian Wolfram Von Soden notes this, writing:

The dog (Sumerian name, ur-gi; Semitic name, Kalbu) was one of the earliest domestic animals and served primarily to protect herds and dwellings against enemies. Despite the fact that dogs roamed freely in the cities, the dog in the ancient Orient was at all times generally bound to a single master and was cared for by him. (91)

Dogs were kept as pets but also as protectors and were often depicted in the company of deities. Inanna (later Ishtar), one of the most popular goddesses in Mesopotamian history, was frequently depicted with her dogs, and Gula, goddess of healing, was closely associated with dogs because of the curative effect of their saliva. People noticed that when a dog was injured it would lick itself to heal; dog saliva was considered an important medicinal substance and the dog a gift of the gods. The dog, in fact, became a symbol of Gula from the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) onward.

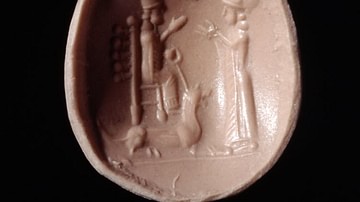

The dog as a protector, however, was as important as its role as healer. During the time of Hammurabi's reign (1792-1750 BCE), dog figurines were regularly cast in clay or bronze and placed under thresholds as protective entities. The scholar E. A. Wallis Budge, writing on discoveries at the city of Kish, notes how "in one room two clay figures of Papsukhal, messenger of the gods, and three figures of dogs were found: the names of two of the dogs are inscribed on them, viz., 'Biter of his enemy' and 'Consumer of his life'" (209). After a ceremony 'awakening' their spirit, these dogs were positioned in buildings to defend against supernatural forces. Joan Lines describes the purpose of these figures further:

Such figurines, made of clay or bronze, were symbols of the Gula-Ninkarrak, goddess of healing and defender of homes. They were buried beneath the floor, usually under the doorstep, to scare away evil spirits and demons and an incantation called "Fierce Dogs" was recited during the ceremony. Many of the dog effigies had their names inscribed on them. (242-243)

These dog statuettes are significant in understanding the Mesopotamian concept of magic and magical protection. The Mesopotamians believed that people were co-workers with the gods to maintain order against the forces of chaos. They took care of the tasks the gods had no time for. In return, the gods gave them all they needed in life. There were many gods in the Mesopotamian pantheon, however, and even though one might mean a person only the best, another could have been offended by one's thoughts or actions. Further, there were ghosts, evil spirits, and demons to be considered. The Mesopotamians, therefore, developed charms, amulets, spells, and rituals for protection, and among these were the dog statuettes.

The Mesopotamians believed that their actions, however small, were recognized and rewarded or punished by the gods and what they did on earth mattered in the heavens. The creation of the dog statuettes drew on the protective power of the spirit of the dog as an eternal and powerful entity, and, through rituals observed in their creation, the figures were imbued with this power. Scholar Carolyn Nakamura comments on this:

Through this production of figurines, Neo-Assyrian apotropaic [evil-averting] rituals trace out complex, and even disorienting, relations between humans, deities, and various supernatural beings in space and time...the creation of powerful supernatural beings in diminutive clay form mimes the divine creation of being from primordial clay. (33)

Just as the gods had created humanity, humans could now create their own helpers. Once created, the dogs performed their important function of protection in concert with other magical artifacts. At Nimrud, Mallowan discovered magical boxes in the rooms of houses which also served to protect the inhabitants. The boxes would be placed in the four corners of a room and often at the four points where a bed would have rested, and were carved with charms to protect against evil spirits and demons. The dogs, buried beneath the entranceways to the home, were the first line of defense against supernatural dangers and the amuletic boxes inside the house provided an added degree of comfort and security.

The Nimrud Dogs

The rituals surrounding dog figurines are exemplified by the location of a set of five such figures discovered by Layard in the 19th century at Nineveh. These were all found under a doorway of the North Palace, and this is in keeping with the practice described above. To ensure maximum protection, it was recommended that one bury two sets of five such figures on either side of a door or beneath the doorway.

At Nimrud, Mallowan found the dog statuettes in a well in the corner of a room of the Northwest Palace. The discovery is described by scholar Ruth A. Horry:

Mallowan's team came across a deep well in the corner of Room NN which was filled with sludge that Mallowan described as being "the consitency of plaster of Paris". No electric pumps were available to dig out the well so the workmen had to scoop out the water and sludge by hand, aided only by the heavy-duty winching equipment borrowed from the Iraq Petroleum Company. It was difficult and dangerous work as the well bottom repeatedly filled up with water...[however] the sludge had provided ideal conditions for preserving materials that would otherwise have decayed, such as fragments of Assyrian rope and wooden well equipment that had accidentally fallen in. (1-2)

Among these other objects were those which had been purposefully thrown into the well during the sack of the city, and included in these were the ivories and the dog statuary. Mallowan interpreted these pieces as being discarded during the destruction of Nimrud - rather than simply thrown in the well by their owners - based on other articles, such as foreign horse harnesses, found with them.

Five of the dog figures were clearly canine and some had their names inscribed on them (just as the ones found at Nineveh did), but the sixth had no name and, further, looked more like a cat. The cat was never considered a protective entity in Mesopotamia, however, and cats are not represented by any amulets or statuary. Horry writes:

Omens portray [cats] as wild animals, at best untameable ones, that wandered in and out of houses at will. Humans and cats lived around each other but did not engage directly...in other words, the inhabitants of Kalhu, even the king in his palace, could not rely on cats to guard a building, whether from mice or more supernatural forces. (2-3)

Mallowan had difficulty in interpreting the piece for this reason: although it looked like a cat, there was no precedent for cat figures or for cats represented in amuletic imagery at all. In his initial reports, he cites the discovery of five dog figurines and one other which was "feline in character" (Horry, 5). The preponderance of evidence, however, argued against interpreting the figure as a cat, and Mallowan later seems to have believed that it was a dog with a "feline appearance" (Horry, 5). Mallowan delivered his finds to the Iraqi authorities, and in keeping with his contract, some went to the Iraqi Museum and some to other institutions. The 'cat' figure was reinterpreted by the British scholars at Cambridge as a cat and remained so until 2013 when the figurines were studied as a group and it was recognized that the cat figure was another dog.

The Dogs Today & Their Significance

The dog figures found at Nineveh are in the British Museum today while the Nimrud Dogs can be found in museums at Baghdad, Iraq; Cambridge, England; New York, America, and Melbourne, Australia. The figures from the Iraq Museum were left untouched in the looting of 2003 and remain a part the permanent collection.

Visitors to these museums quite rightly marvel at exhibits of Mesopotamian art such as the famous Nimrud Ivories but often overlook the dog figurines. Even in those exhibits where their history is told, the focus is largely on their discovery with only brief mention of what they meant to the people who created them. Often, it seems, the small dogs are interpreted by visitors as representations of ancient pets. The dog statuettes did not represent beloved pets, however, but divine protection. They were created to keep safe the people one cared for. Centuries ago, people crafted the dog figures, gave them life through ritual, and buried them beneath their doorway for peace of mind.

In the same way, an individual living today might install a security system in the home, make sure doors and locks are secure, perhaps even hang a religious symbol or totemic talisman near the door. The Nimrud Dogs are significant artifacts because they are so personal. Nakamura comments on their creation and use, noting how "an idiom of protection arises in material enactment of memory" (33). The "enactment of memory" in the past had to do with the awakening of the spirit of the dog in the figurine. Today, however, the Nimrud Dogs evoke the spirit of the past and the memory of those who created the figures to protect themselves and those they loved from harm.