The gods of ancient Egypt freely gave their bounty to the people who worked the land, but this did not exempt those farmers from paying taxes on that bounty to the government. Egypt was a cashless society until the Persian Period (c. 525 BCE), and the economy depended upon agriculture and barter.

The monetary unit was the deben, approximately 90 grams of copper, and trade was based on an 'imaginary' deben: if fifty deben purchased a pair of sandals, then a pair of sandals could be traded for fifty deben worth of wheat or beer.

This was the system the central government operated on in collecting taxes. Scholar Andre Dollinger writes:

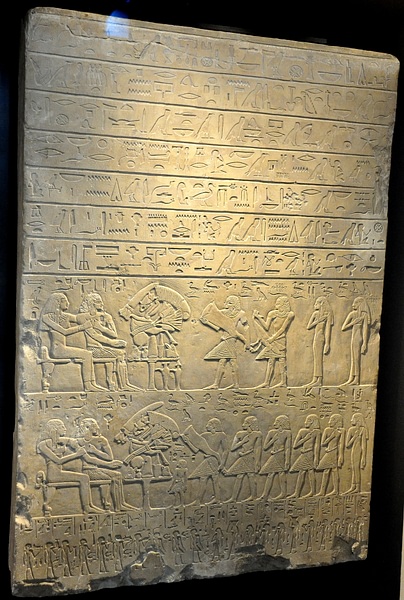

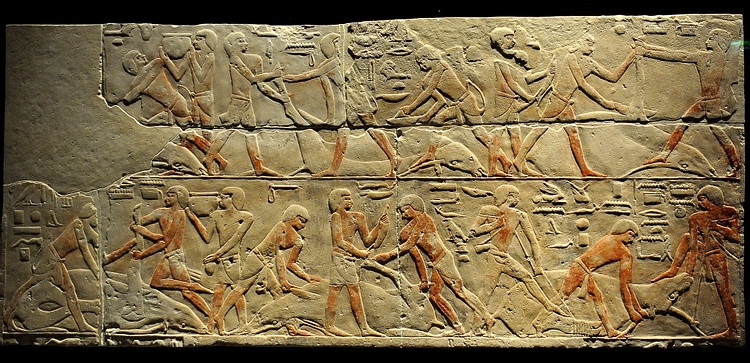

In a barter economy, the simplest way to exact taxes is by seizing part of the produce, merchandise, or property. The agricultural sector of such an economy is easiest to tax. A farmer cannot deny possession of a field without losing his rights. The field can be measured, the yield assessed, and the produce is difficult to hide because of its large bulk. It is no wonder that peasants were the highest and most consistently taxed part of the population. (1)

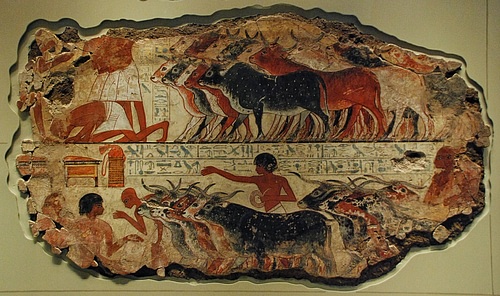

The Cattle Count

The best way for a king to assess what was due him from the regions of his country was to go out and see it for himself. As early as the reign of Hor-Aha (c. 3100-3050 BCE), institutionalized during the Second Dynasty (c. 2890 - c. 2670 BCE), and continuing through the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE), an annual event was instituted known as the Shemsu Hor (Following of Horus), better known as the Egyptian Cattle Count, during which the king and his retinue would travel the land, assess the value of farmers' crops, and collect a certain amount in taxes. Scholar Toby Wilkinson comments on this, writing:

The Shemsu Hor would have served several purposes at once. It allowed the monarch to be a visible presence in the life of his subjects, enabled his officials to keep a close eye on everything that was happening in the country at large, implementing policies, resolving disputes, and dispensing justice; defrayed the costs of maintaining the court and removed the burden of supporting it year-round in one location; and, last but by no means least, facilitated the systematic assessment and levying of taxes. A little later, in the Second Dynasty, the court explicitly recognized the actuarial potential of the Following of Horus. Thereafter, the event was combined with a formal census of the country's agricultural wealth. (44-45)

Egypt was divided into districts, and the fields and produce of every district were assessed for taxes. Each district (nome) was divided into provinces with a nomarch administering the overall operation of the nome, and then lesser provincial officials, and mayors of the towns operating in lesser and lesser spheres of authority. Rather than trust a nomarch to accurately report his wealth to the government, the king would personally visit each nome and collect the taxes himself. The Shemsu Hor thus became an important annual (later bi-annual) event in the lives of the Egyptians. Oil, beer, ceramics, livestock, and every other kind of commodity would be taxed, but the most important was the tax on grain.

Grain Tax & Redistribution

Grain not only fed the population of Egypt but was essential for trade with other countries. Whatever resources Egypt lacked could be purchased through the sale of grain, and since Egypt had fertile fields which usually produced abundant crops, grain was most important to the operation of the government. Not only did they use grain in trade but stored it in surplus to feed the people in years of poor harvest and to distribute to communities which might suffer some misfortune. Scholar Edward Bleiberg explains how the process worked:

The ancient Egyptian government met its needs for food, raw materials, manufactured goods, and labor through taxation and conscription. The pre-market, essentially money-less, Egyptian economy was structured so the residents of the Nile Valley provided support for the king and other government institutions while at the same time the king redistributed these essential commodities to each class on the basis of rank and status in society. (cited in Bard, 761-762)

Taxes & the Old Kingdom

Taxes from the Egyptian Cattle Count and the lucrative trade it enabled provided the central government of the Old Kingdom with the great wealth required to build the pyramids at Giza. In the modern day, only the Great Pyramid of Khufu and those of Khafre and Menkaure rise from the Giza plateau along with the Great Sphinx and a number of lesser monuments, but in its day, each pyramid at Giza had its own pyramid complex, there was housing for the workers, markets, separate temples, workshops; and all of these cost a great deal of money. Further, once the pyramids, complexes, and temples were completed, staff had to be hired to maintain them and preside over the rituals which would ensure the eternal life of the king in the world to come.

All of these building projects and attendant rituals were very expensive and eventually contributed to what is known as the Old Kingdom collapse during the reign of Pepi II (2278-2184 BCE). The strain on the central government's treasury, paying not only for the labor, materials, and transport of those materials to the site but also for the clergy and their staff to maintain the temples, was finally too great a burden.

Further, in return for their services, the rulers of the Old Kingdom had exempted the priesthood from taxation in perpetuity. Since the priests had, by this time amassed a great amount of land, the loss in taxes was significant.

Although the central government finally failed in the Sixth Dynasty, the government was already in trouble toward the end of the Fourth Dynasty (during which the pyramids of Giza were built) in the reign of Menkaure's successor, Shepsekaf (2503-2498 BCE). Shepsekaf had enough money and resources to complete Menkaure's pyramid and temple complex but was himself buried in a modest tomb at Saqqara.

Taxes During the First Intermediate Period

The Old Kingdom's decline led to the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) during which the individual nomarchs had more power than the central government. The practice of the yearly Cattle Count was discontinued; taxes, however, were not. The king no longer was able to command collection of taxes, but the individual nomarchs were and did. Scholar Rosalie David writes:

In theory, the king owned all land and possessions. In reality, although he was the largest landowner and possessed areas within each nome, the temples and even private individuals owned substantial real estate. (95)

The king was thought to own all the land because he had been granted his position by the gods, who had created the world and given it to the people, but throughout Egypt's history the king would struggle with the priesthood, especially the priests of Amun, for power because the temples and their fertile lands and fields had been declared tax-exempt. This situation allowed for the clergy to amass a great deal of wealth and attendant power at the expense of the central government.

The nomarchs now kept the larger part of the taxes collected for themselves, although a portion continued to be sent to the capital as before. This is the reason one does not find great monuments like the pyramids of Giza constructed during the First Intermediate Period but one does find elaborate personal tombs of nomarchs and other nobility. This period ended when prince Mentuhotep II of Thebes (c. 2061-2010 BCE) united the country under his rule and initiated the era of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). Once again, a strong central government ruled Egypt and taxes enabled rulers to afford grand building projects. The towering Temple of Karnak near Thebes was begun during this time in the reign of Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE).

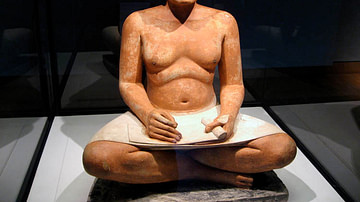

Calculations of Taxes through the New Kingdom

Taxes were now assessed and collected by officials charged with that duty. This practice of sending out tax collectors had actually begun toward the end of the Old Kingdom when the practice of the Cattle Count had begun to decline. Tax collectors who held back on the full amount due the government were severely punished. The Middle Kingdom, considered a classical age in Egypt's history, declined during the 13th Dynasty allowing for the Hyksos, a foreign people, to gain a foothold in the Delta region of Lower Egypt. The time of the Hyksos is known as the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE) during which, again, individual nomarchs benefited most from taxation and conscripted those who could not pay for labor.

The Second Intermediate Period gave way to the time of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) when Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos from Egypt and founded the 18th Dynasty. The New Kingdom is the period of Egypt's empire and a professional army to spread and maintain it. It is also the era best known for its rulers and the monuments they raised. Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Horemheb, Seti I, Ramesses the Great, Merenptah, Ramesses III, all ruled during the New Kingdom and all contributed their own impressive monuments to the culture paid for, largely, through taxes. Rosalie David writes:

There is more information about taxation in the New Kingdom than there is for earlier periods; for example, in the reign of Thutmose III it is known that taxes were collected in the form of cereals, livestock, fruit, and provisions, as well as gold and silver rings and jewels. The governors annually assessed the cereal payable for that year, basing their calculations on the surface area of each nome and the height of the Nile rising. The levels of inundation were recorded on nilometers; built at the river's edge, nilometers were designed to measure the annual height of the inundation. If there was a low Nile when the water did not reach the usual level, the tax to be paid that year was reduced accordingly. (95)

The Third Intermediate & Late Period

The New Kingdom was followed by the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE) during which rule of the country was initially divided between the cities of Tanis and Thebes. Individual nomarchs again were able to gain substantial power, and land was given to professional soldiers who served well and were able to keep a significant amount of their produce for themselves without paying tax. The priests of Amun, especially at Thebes, held enormous acreage of tax-free land while the farmers who worked it continued to pay them what amounted to a tax which they then used for whatever purposes they desired.

Taxes were so heavy that many people fell into debt, and during the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (c. 525-332 BCE), people would sell themselves into service, offering their time and labor to pay off their taxes. Inability to pay these taxes, or the loans given to a person which were then called due, resulted in people selling themselves to be officially recognized as another person's son. The adopter would then pay the debt and the 'son' would work off what was owed. In many cases, this arrangement worked well for all involved since a childless couple could adopt someone who would then make sure they were given a proper burial with all rites and the adopted son would inherit their land once they passed on.

The old tradition of the Cattle Count, when the king would travel among his people to assess a fair tax of the land, had been long forgotten by this time. The Cattle Count would prove important for later historians in that records of it clearly marked the dates on which it was conducted and provided an annual (later bi-annual) record of the history of the time. In the early 20th century CE, the Cattle Count became one of the more or less accurate means of dating Egyptian history.

To the people of the time, however, the early Cattle Count ritual would have been regarded in much the same way as tax time is in many countries around the world today. No one liked paying taxes in ancient Egypt any more than they do now, but the Cattle Count at least provided a semblance of participating in one's government. The king and his court personally visited the districts and assessed the land, and even though precise details of this practice are unknown, the effort was most likely appreciated far more than the later visits by the tax collectors.