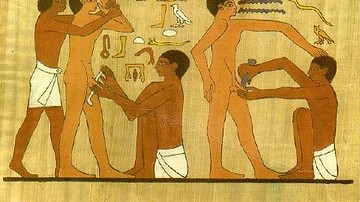

Medicine in ancient Egypt was understood as a combination of practical technique and magical incantation and ritual. Although physical injury was usually addressed pragmatically through bandages, splints, and salves, even the broken bones and surgical procedures described in the medical texts were thought to have been made more effective through magic spells.

These spells were recorded in the medical texts of the time, written on papyrus scrolls, and consulted by physicians when needed. In the present day, most people would balk at the idea of visiting a doctor and having incantations muttered over them while they were rubbed with oil and fumigated with incense as amulets and charms were swung over their bodies, but to the ancient Egyptians, this was all simply a routine aspect of the medical practice. As the Ebers Papyrus, one of the medical texts of its day, states, "Magic is effective together with medicine. Medicine is effective together with magic."

Magic & Medicine

The Egyptian god of magic was also their god of medicine, Heka, who carried a staff entwined with two serpents (no doubt taken from the Sumerian god Ninazu, son of the goddess of health and healing, Gula). This symbol later traveled to Greece where it became the caduceus scepter of the healing god Asclepius and later associated with the "father of medicine," Hippocrates. The caduceus is recognized today as the symbol of the medical profession around the world. Magical practice and incantations invoked the power of the gods to accomplish one's goals, whether in medicine in in any other area of one's life. In medical practice, the spells, hymns, and incantations drew the gods near to the healer and focused their energies on the patient. Heka was the name of the god and also the practice of magic. According to Egyptologist Margaret Bunson:

Three basic elements were always involved in the practice of heka: the spell, the ritual, and the magician. Spells were traditional but also changed with the times and contained words which were viewed as powerful weapons in the hands of the learned. (154)

Doctors were well versed in magic and how it should be used most effectively. The doctor was the magician who knew the spells and the rituals which would unlock their power. When a doctor was called to a patient, he or she was expected to be able to cure the ailment because the gods would arrive once the proper spells were incanted along with the precise rituals. The triad of a doctor, spell, and ritual was considered as reliable by the ancient Egyptians as any medical procedure in the present day.

The Papyrus Scrolls

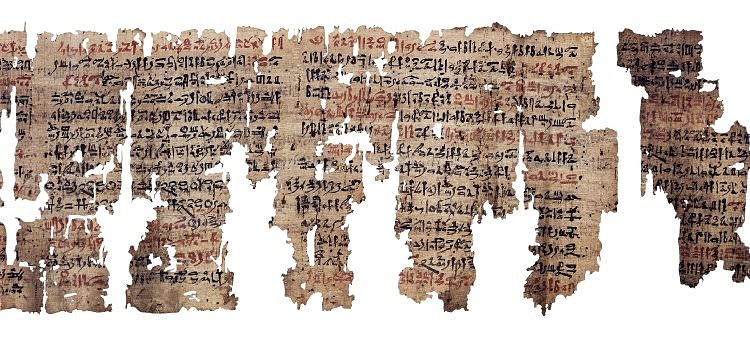

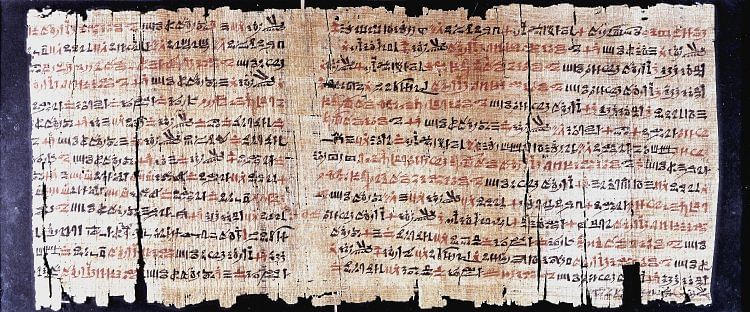

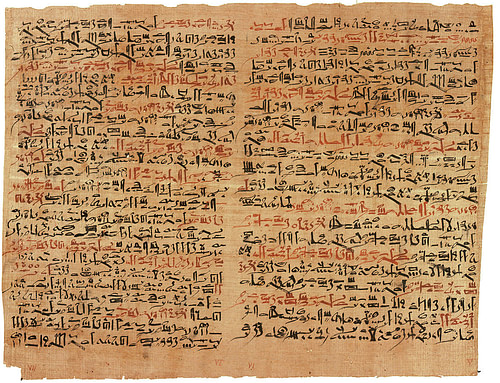

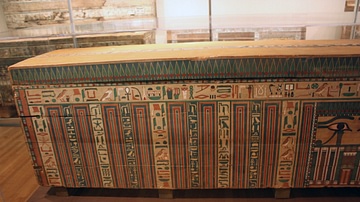

These spells were written down on scrolls made from the papyrus plant which was cut in strips, laid in layers, and pressed to create paper. These scrolls had two sides: the recto, where the fibers of the plant ran horizontally (the front) and the verso, where they ran vertically (the back). The recto was written on first as this was the preferred surface, but once this was filled, the verso was used for additional information or, sometimes, a completely different text. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, for example, has surgical procedures written on the recto with magical spells on the verso. Although some scholars have interpreted the two sides as a whole text, others have suggested that the spells were added to the papyrus later. Papyrus was fairly expensive and so was often recycled for other works either by writing over the recto side or using the verso or both.

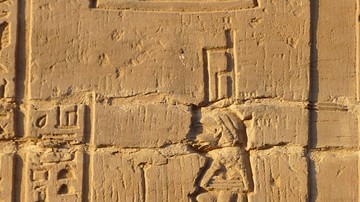

The medical scrolls were preserved in a part of the temple known as the Per-Ankh ('House of Life'), which was an interesting combination of scriptorium, center of learning, library, and possibly hospital or medical school. Doctors were said to operate out of the Per-Ankh, but whether this meant they treated patients there, studied there, or simply referred to the knowledge they had obtained is unclear; it is possible the phrase meant all of the above. Temple complexes in ancient Egypt did serve as a kind of hospital and people are recorded as visiting them for assistance with medical problems. At the same time, of course, they were associated with centers of learning.

The spells which medical professionals would have learned were not considered arbitrary but had been proven effective through experience. The tone of authority in all of the medical texts implies empirical knowledge of the success of the prescriptions and procedures. The Erman Medical Papyrus, for example, authoritatively gives incantations and magical spells for the protection of children and healthy pregnancies. This text, dated to the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782-c. 1570 BCE) and most likely to c. 1600 BCE, is interesting for a number of reasons but, notably, for its reflection of medical knowledge in folk practice. The Magical Lullaby of ancient Egypt, sung or recited by mothers to protect their children from supernatural harm, shares many similarities with the incantations suggested in the Erman papyrus.

The Medical Texts

The different medical texts each address a different aspect of disease or injury. Each of them carries the name of the individual in the modern era who discovered, purchased, or donated the text to the museum which now houses it. The names by which the works were originally known have been lost.

Although there are many different papyri which mention magical spells, medical procedures, or both, only those directly associated with the practice of medicine - and thought to have been consulted by practicing doctors - are given below. A manuscript such as the Westcar Papyrus, for example, while it does shed light on practices surrounding birth, cannot be considered a medical text since it is obviously historical fiction.

The Berlin Medical Papyrus (Brugsch Papyrus) - Dated to the early New Kingdom of Egypt, this work is considered a copy of a much older medical treatise from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE). The papyrus deals with contraception and fertility and includes instruction on the earliest known pregnancy tests in which a urine sample was taken from the woman and poured over vegetation; changes in hormone levels would be evident in the effect the urine had on the plants. Much of the advice in this work is also found in the Ebers Papyrus.

The Carlsberg Papyrus - A collection of different papyri from different eras spanning centuries. Parts of this papyrus date from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, some from the New Kingdom, and others from as late as the 1st century CE. The New Kingdom segment is considered a copy of a text from the Middle Kingdom dealing with gynaecological issues, pregnancy, and eye problems. The different parts are written in hieratic, demotic, and ancient Greek.

The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus (also known as Papyrus Chester Beatty VI) - Dated to the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE), and specifically to c. 1200 BCE, the text is written in demotic script and is the oldest treatise on anorectal disease (affecting the anus and rectum) in history. The work prescribes cannabis as an effective pain medication for what seems to be colorectal cancer as well as headaches; thus making the work an early instance of medicinal cannabis prescribed for cancer patients, predating Herodotus' mention of the Scythian's use of cannabis as a recreational hallucinogen in his Histories (5th century BCE), which is generally considered the oldest mention of the drug.

The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden - Dated to the 3rd century CE, this papyrus is written in demotic script and deals wholly with the supernatural aspects of disease, including spells for divination and raising someone from the dead. Advice is given to the doctor on how to induce visions and make contact with supernatural entities to cure a patient by driving out evil spirits.

The Ebers Papyrus - This copy, dated to the New Kingdom (specifically c. 1550 BCE), is also an older work from the Middle Kingdom. It discusses cancer (about which it says one can do nothing), heart disease, depression, diabetes, birth control, and many other concerns such as digestive problems and urinary tract infections. It offers both 'scientific' and supernatural diagnoses for disease and cure and includes a number of spells. It is the longest and most complete ancient Egyptian medical text found to date containing over 700 prescriptions and spells. Although the Egyptians had little knowledge of internal organs, they understood the heart was a pump which supplied blood to the rest of the body. Psychological problems are attributed to supernatural causes in the text in the same way physical disease is.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus - From the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE), this work is a copy of an earlier piece probably written in the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE). It is in hieratic script and dated to c. 1600 BCE. Some scholars attribute the original work to Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE), best known as the architect of Djoser's Step Pyramid constructed toward the end of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE). Imhotep was also well respected for his medical treatises arguing that disease was natural, not a punishment from the gods or the result of evil spirits. Since the Edwin Smith Papyrus focuses on pragmatic treatments for injuries, Imhotep's claims would have at least influenced the work even if he did not write the original. It is the oldest known work on surgical techniques and was probably written for triage surgeons in field hospitals. The work focuses on practical application of easing pain and setting broken bones. As noted, the eight spells which appear on the verso side are considered by some scholars to be a later addition to the scroll.

The Hearst Medical Papyrus - A New Kingdom copy in hieratic script of an older work thought to have been written in the period of the Middle Kingdom. The Hearst Medical Papyrus contains prescriptions for urinary tract infections, digestive problems, and other similar maladies. Although its authenticity has been questioned, it is generally accepted as legitimate. A number of the prescriptions repeat those found in the Ebers Papyrus and echoed in the Berlin Papyrus.

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus - Dated to the Middle Kingdom (specifically c. 1800 BCE), this papyrus deals with women's health and is thought to be the oldest such document on the subject. It covers contraception, conception, and pregnancy issues, as well as attendant problems linked to menstruation. It suggests that a woman with a severe headache, for example, is experiencing "discharges of the womb" and should be disinfected with incense, rubbed with oil, and the doctor should "have her eat a fresh ass liver" in order to recover. Many of the prescriptions deal with troubles emanating "from the womb" because, as Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes, there was the "mistaken assumption that a healthy woman had a free passageway connecting her womb to the rest of her body" (33). Supernatural or natural disturbances in the womb, therefore, would affect the entire system of the individual, and so the womb becomes the focus in this work. Another medical text, The Ramasseum Medical Papyrus, is considered a New Kingdom copy of parts of this text.

The London Medical Papyrus - Dated to the Second Intermediate Period, this scroll consists of medicinal prescriptions and magical spells dealing with problems associated with the skin, eyes, pregnancy, and burns. The spells are to be used in conjunction with the medical applications, and the work is thought to have been a common reference book carried by practicing doctors. Some spells drive away evil spirits or ghosts while others were used to boost the healing properties of whatever treatment was applied.

Conclusion

All of these texts were as vital to the practice of medicine in ancient Egypt as any medical text in the present day. The prescriptions and procedures, which had proven effective in the past, were written down and preserved for other practitioners. Bunson writes:

Diagnostic procedures for injuries and diseases were common and extensive in Egyptian medical practice. The physicians consulted texts and made their own observations. Each physician listed the symptoms evident in a patient and then decided whether he had the skill to treat the condition. If a priest determined that a cure was possible, he reconsidered the remedies or therapeutic regimens available and proceeded accordingly. (158)

The skill of the Egyptian physician was widely recognized throughout the ancient world and their medical knowledge and procedures were emulated by the Greeks. Greek medicine was just as admired by Rome which adopted the same kinds of practices with the same sort of understanding of supernatural influences. The great Roman physician Galen (126 - c. 216 CE) was long understood to have learned his art from Cleopatra of Egypt, though a different Cleopatra from the famous queen. Roman medical practices lay the foundation for later understanding of the art of healing, and in this way, the ancient Egyptian texts continued to influence the medical profession up through the present day.