In ancient Egypt, if a woman were having difficulty conceiving a child, she might spend an evening in a Bes Chamber (also known as an incubation chamber) located within a temple. Bes was the god of childbirth, sexuality, fertility, among other his other responsibilities, and it was thought an evening in the god's presence would encourage conception. Women would carry Bes amulets, wear Bes tattoos, in an effort to encourage fertility.

Once a child was born, Bes images and amulets were used in protection as he or she grew and, later, the child would become an adult who adopted these same rituals and beliefs in daily life. At death, the person was thought to move on to another plane of existence, the land of the gods, and the rituals surrounding burial were based on the same understanding one had known all of one's life: that supernatural powers were as real as any other aspect of existence and the universe was infused by magic.

Magic in ancient Egypt was not a parlor trick or illusion; it was the harnessing of the powers of natural laws, conceived of as supernatural entities, in order to achieve a certain goal. To the Egyptians, a world without magic was inconceivable. It was through magic that the world had been created, magic sustained the world daily, magic healed when one was sick, gave when one had nothing, and assured one of eternal life after death. The Egyptologist James Henry Breasted has famously remarked how magic infused every aspect of ancient Egyptian life and was "as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food" (200). Magic was present in one's conception, birth, life, death, and afterlife and was represented by a god who was older than creation: Heka.

Heka

Heka was the god of magic and the practice of the art itself. A magician-priest or priest-physician would invoke Heka in the practice of heka. The god was known as early as the Pre-Dynastic period (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE), developed during the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) and appears in The Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) and the Coffin Texts of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE). Heka never had a temple, cult following, or formal worship for the simple reason that he was so all-pervasive he permeated every area of Egyptian life.

Like the goddess Ma'at, who also never had a formal cult or temple, Heka was considered the underlying force of the visible and invisible world. Ma'at represented the central Egyptian value of balance and harmony while Heka was the power which made balance, harmony, and every other concept or aspect of life possible. In the Coffin Texts, Heka claims this primordial power stating, "To me belonged the universe before you gods came into being. You have come afterwards because I am Heka" (Spell 261). After creation, Heka sustained the world as the power which gave the gods their abilities. Even the gods feared him and, in the words of Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson, "he was viewed as a god of inestimable power" (110). This power was evident in one's daily life: the world operated as it did because of the gods and the gods were able to perform their duties because of Heka.

Magic & Religion

The priests of the temple cults understood this but their function was to honor and care for their particular deity and ensure a reciprocity between that god and the people. The priests or priestesses, therefore, would not invoke Heka directly because he was already present in the power of the deity they served.

Magic in religious practice took the form of establishing what was already known about the gods and how the world worked. In the words of Egyptologist Jan Assman, the rituals of the temple "predominantly aimed at maintenance and stability" (4). Egyptologist Margaret Bunson clarifies:

The main function of priests appears to have remained constant; they kept the temple and sanctuary areas pure, conducted the cultic rituals and observances, and performed the great festival ceremonies for the public. (208)

In their role as defenders of the faith, they were also expected to be able to display the power of their god against those of any other nation. A famous example of this is given in the biblical book of Exodus (7:10-12) when Moses and Aaron confront the Egyptian "wise men and sorcerors".

The priest was the intermediary between the gods and the people but, in daily life, individuals could commune with the gods through their own private practices. Whatever other duties the priest engaged in, as Assman points out, his primary importance was in imparting to people theological meaning through mythological narratives. They might offer counsel or advice or material goods but, in cases of sickness or injury or mental illness, another professional was consulted: the physician.

Magic & Medicine

Heka was the god of medicine as well as magic and for good reason: the two were considered equally important by medical professionals. There was a kind of doctor with the title of swnw (general practitioner) and another known as a sau (magical practitioner) denoting their respective areas of expertise but magic was widely used by both. Doctors operated out of an institution known as the Per-Ankh ("The House of Life"), a part of a temple where medical texts were written, copied, studied, and discussed.

The medical texts of ancient Egypt contain spells as well as what one today would consider 'practical measures' in treating disease and injury. Disease was considered supernatural in origin throughout Egypt's history even though the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) had written medical treatises explaining that disease could occur naturally and was not necessarily a punishment sent by the gods.

The priest-physician-magician would carefully examine and question a patient to determine the nature of the problem and would then invoke whatever god seemed most appropriate to deal with it. Disease was a disruption of the natural order and so, unlike the role of the temple priest who maintained the people's belief in the gods through standard rituals, the physician was dealing with powerful and unpredictable forces which had to be summoned and controlled expertly.

Doctors, even in rural villages, were expensive and so people often sought medical assistance from someone who might have once worked with a doctor or had acquired some medical knowledge in some other way. These individuals seem to have regularly set broken bones or prescribed herbal remedies but would not have been thought authorized to invoke a spell for healing. That would have been the official view on the subject, however; it seems a number of people who were not considered doctors still practiced medicine of a sort through magical means.

Magic in Daily Life

Among these were the seers, wise women who could see the future and were also instrumental in healing. Egyptologist Rosalie David notes how, "it has been suggested that such seers may have been a regular aspect of practical religion in the New Kingdom and possibly even in earlier times" (281). Seers could help women conceive, interpret dreams, and prescribed herbal remedies for diseases. Although the majority of Egyptians were illiterate, it seems some people - like the seers - could memorize spells read to them for later use.

Egyptians of every social class from the king to the peasant believed in and relied upon magic in their daily lives. Evidence for this practice comes from the number of amulets and charms found through excavations, inscriptions on obelisks, monuments, palaces, and temples, tomb engravings, personal and official correspondence, inscriptions, and grave goods. Rosalie David explains that "magic had been given by the gods to mankind as a means of self-defense and this could be exercised by the king or by magicians who effectively took on the role of the gods" (283). When a king, magician, or doctor was unavailable, however, everyday people performed their own rituals.

Charms and spells were used to increase fertility, for luck in business, for improved health, and also to curse an enemy. One's name was considered one's identity but Egyptians believed that everyone also had a secret name (the ren) which only the individual and the gods knew. To discover one's secret name was to gain power over them. Even if one could not discover another person's ren they could still exercise control by slandering the person's name or even erasing that person's name from history.

Magic in Death

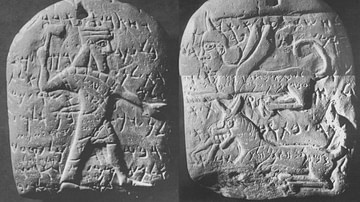

Just as magic was involved in one's birth and life, so was it present at one's departure to the next world. Mummification was practiced in order to preserve the body so that it could be recognized by the soul in the afterlife. The last act of the priests at a funeral was the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony during which they would touch the mummified corpse with different objects at various places on the body in order to restore the use of ears, eyes, mouth, and nose. Through this magical ritual the departed would be able to see and hear, smell and taste, and speak in the afterlife.

Amulets were wrapped with the mummy for protection and grave goods were included in the tomb to help the departed soul in the next world. Many grave goods were practical items or favorite objects they had enjoyed in life but many others were magical charms or objects which could be called upon for assistance.

The best known of these type were the shabti dolls. These were figures made of faience or wood or any other kind of material which sometimes looked like the deceased. Since the afterlife was considered a continuation of one's earthly life, the shabti could be called upon to work for one in The Field of Reeds. Spell 472 of the Coffin Texts (repeated later as Spell 6 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead) is given to bring the Shabti to life when one needs to so one can continue to enjoy the afterlife without worrying about work.

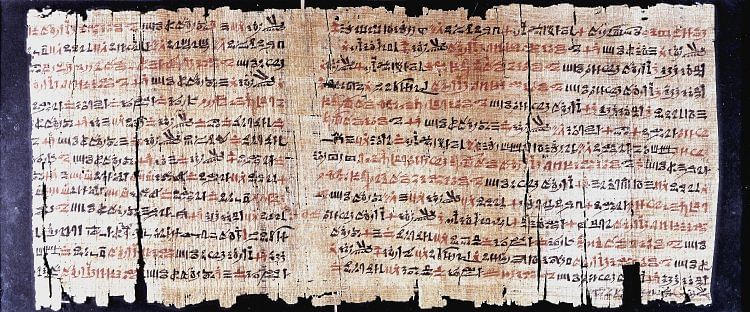

The Egyptian Book of the Dead exemplifies the belief in magic at work in the afterlife. The text contains 190 spells to help the soul navigate the afterlife to reach the paradise of The Field of Reeds, an eternal paradise which perfectly reflected one's life on earth but without disappointment, disease or the fear of death and loss. Throughout The Egyptian Book of the Dead the soul is instructed which spells to use to pass across certain rooms, enter doors, transform one's self into different animals to escape dangers, and how to answer the questions of the gods and those of their realm. All of these spells would have seemed as natural to an ancient Egyptian as detailed directions on a map would be to anyone today - and just as reasonable.

Conclusion

It may seem strange to a modern mind to equate magical solutions with reason but this is simply because, today, one has grown used to a completely different paradigm than the one which prevailed in ancient Egypt. This does not mean, however, that their understanding was misguided or `primitive' and the present one is sophisticated and correct. In the present, one believes that the model of the world and the universe collectively recognized as 'true' is the best model possible precisely because it is true. According to this understanding, beliefs which differ from one's truth must be wrong but this is not necessarily so.

The scholar C.S. Lewis is best known for his fantasy works about the land of Narnia but he wrote many other books and articles on literature, society, religion, and culture. In his book The Discarded Image, Lewis argues that societies do not dismiss the old paradigms because the new ones are found to be more true but because the old belief system no longer suits a society's needs. The prevailing beliefs of the modern world which people consider more advanced than those of the past are not necessarily more true but only more acceptable. People in the present day accept these concepts as true because they fit their model of how the world works.

This was precisely the same way in which the ancient Egyptians saw their world. The model of the world as they understood it contained magic as an essential element and this was completely reasonable to them. All of life had come from the gods and these gods were not distant beings but friends and neighbors who inhabited the temple in the city, the trees by the stream, the river which gave life, the fields one plowed. Every civilization in any given era believes that it knows and operates on the basis of truth; if they did not, they would change.

When the model of the world changed for ancient Egypt c. 4th century CE - from a henotheistic/polytheistic understanding to the monotheism of Christianity - their understanding of 'truth' also changed and the kind of magic they recognized as imbuing their lives was exchanged for a new pardigm which fit their new understanding. This does not mean that new understanding was correct or more 'true' than what they had believed in for millenia; merely that it was now more acceptable.