The dog as "man's best friend" has a long history going back to the ages long before the civilization of ancient Egypt was established but the Egyptians were among the earliest people to recognize the value of the dog and show their appreciation for its particular skills and talents.

Ancient Egypt is well known for its association with cats but the dog was equally popular and highly regarded. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson notes that dogs "were probably domesticated in Egypt in the Pre-Dynastic eras" and they "served as hunters and as companions for the Egyptians and some mentioned their hounds in their mortuary texts" (67). An early tomb painting dated to c. 3500 BCE shows a man walking his dog on a leash in a scene recognizable to anyone in the modern day.

The dog collar and leash were most likely developed by the Sumerians earlier although evidence for both of these in Mesopotamia appears later than 3500 BCE in objects like a golden Saluki pendant from Ur dated to 3300 BCE. It is probable, however, that the Sumerians - among their many other inventions - also created the dog collar and leash since the dog was domesticated earlier in that region than in Egypt.

Domestication & the Dog

Animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, asses, and different kinds of birds were domesticated in the Pre-Dynastic Period (c.6000 - c. 3150 BCE) as evidenced by grave goods and overuse of the land for grazing. By the time of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) cattle were the most important animal and were regarded as objects of substantial wealth as made clear through the Egyptian Cattle Count which was a form of calculating and collecting taxes.

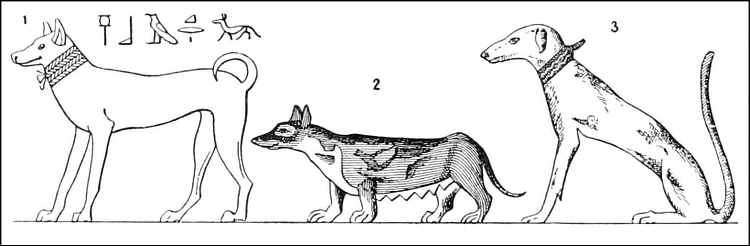

Prior to the domestication of any of these animals, however, is that of the dog. Scholars have reached this conclusion based upon physical evidence from graves as well as inscriptions and tomb paintings. The dog, either a Basenji, Greyhound, or Saluki, is frequently depicted helping to herd cattle, wearing a wide collar fastened with a bow at the back of the neck.

According to historian Jimmy Dunn, dogs "served a role in hunting, as guard and police dogs, in military actions, and as household pets" (1). The Egyptian word for dog was iwiw which referenced their bark (Dunn, 1). Whether as hunters and companions or guards, police, or religious figures, the dog was a common feature of the ancient Egyptian landscape.

Egyptian Dog Breeds

Dogs are represented in Egyptian art work from the Pre-Dynastic Period forwards either as companions, at the hunt, or in afterlife vignettes. They also appear on ceramics such as the siltstone palettes which were used in daily life (such as the Four Dogs Palette at the Louvre for cosmetics) or in ceremonies or commemorations (as with the Narmer Palette).

The kinds of breeds are sometimes difficult to identify but, essentially, seem to be of seven distinct kinds. Hunting dogs were regularly referred to as tesem, a term which has attached itself to the ancestors of the Basenji, but could have been applied as easily to any dogs used in the hunt.

A tesem was not a breed of dog but designated a hunting dog. The following breeds are identified by their modern names but it should be understood that these were not the names they were known by in ancient Egypt except, perhaps, for the Basenji and Ibizan.

The Basenji: This breed is among the best attested to in ancient Egypt. It no doubt came from Nubia where it seems to have been quite common. The name is usually translated as "dog of the villagers" because it was so commonly associated with communities of people. The Basenji was used in hunting small game and as a companion, family pet, and guard dog. Basenjis could be among the dogs on the funerary stele of Intef II (2112-2063 BCE) of the 11th Dynasty and possibly his favorite dog, Beha, for whom he had an individual stele carved.

The Greyhound: Although the origin of the Greyhound is contested, evidence of the breed has been found in both Mesopotamia and Egypt. Graves containing Greyhounds in Mesopotamia date back to the Ubaid Period c. 5000 BCE and in Egyptian images c. 4250 BCE. The Greyhound was used in open-area hunts for large game but was also kept as a pet and a guard dog. Greyhounds are depicted throughout Egypt's history as a hunting dog but may also be the breed featured in battle scenes like the Victory Stele of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) celebrating his triumph over the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh.

The Ibizan: Probably the dog most often represented in Egyptian art. The Ibizan is of Egyptian origin but was brought from Egypt to the island of Ibiza by Phoenician traders sometime in the 7th century BCE. The breed, and its name, is usually dated from this time but there is no evidence of the dog on the island of Ibiza originally while there is a great deal suggesting its presence in Egypt. This is the dog most often referred to as the tesem and so the 'typical' Egyptian dog.

The Pharaoh: This breed is routinely claimed to have originated much later, in the 17th century CE on Malta, but its ancestors are thought to have been kept by the ancient Egyptians. Most likely it was an Egyptian breed brought to Malta by Phoenician traders. This claim is based upon art work, such as that on the tomb of Intef II toward the end of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE). His funerary stele depicts dogs which resemble a breed similar to the later pharaoh hound more than other known Egyptian breeds. The Pharaoh is often depicted in hunting scenes and was considered the best breed for sacrifice to Anubis at Cynopolis.

The Saluki: First bred in Mesopotamia by the Sumerians, the Saluki was one of the most popular breeds in the region and, later, in Egypt. Amulets and art work in Mesopotamia regularly depict this breed and it has been found in graves with and without human remains accompanying the bones. The Saluki (or Sloughi breed) was definitely present in Egypt, in spite of claims to the contrary, just not as early as in Mesopotamia. Salukis are clearly represented in tomb paintings and stelae as hunting dogs and companions.

The Whippet: Whippets were the dogs of the Egyptian kings and most likely originated through the breeding of Greyhounds with pariah dogs. The result was a smaller, faster, hunting dog. Whippets were popular for hunting in open terrain where they could make the best use of their speed in bringing down game. Although they are sometimes cited as a late breed in Egypt they seem to be the dogs represented in art from the Old Kingdom onwards.

The Molossian: Bred in Greece in the region of Epirus, these dogs came to Egypt through trade. They take their name from the king of Epirus, Molossus, said to be the grandson of Achilles. These dogs, or some variant of them, were well-known hunters and guard dogs in Mesopotamia and were used by the Egyptians for the same purpose but also as police dogs. They may be among the dogs, like the greyhound, depicted on the Kadesh Victory Stele of Ramesses II. The Molossus would later become best known as the fighting and war dogs of ancient Rome but seem to have become quite popular in Egypt and were most likely introduced by the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-c.1570 BCE).

There were also pariah dogs, wild dogs and strays of mixed breed, who often hunted around the outskirts of a village or necropolis. These dogs often traveled in packs and scavenged for food. It has been suggested that the presence of pariah dogs encouraged the Egyptian practice of burial in tombs to protect the remains from them. In the early Pre-Dynastic Period the dead were buried in simple earthen graves, often quite shallow, which allowed for the pariah dogs to easily dig down and disturb them. The mastaba tomb may have, in part, developed to prevent this.

Ancient Egyptian inscriptions mention the ketket but, like the tesem, this was not a breed of dog but a description of a kind of dog. Ket means `little' in ancient Egyptian and so a ketket was any kind of small dog. Dogs which seem to be the ancestors of the modern harrier also were kept by the Egyptians but what this breed was is unknown. They seem to have been small or medium dogs of impressive speed.

An example of a dog who would've been called a ketket is the small statue presently in the British Museum known as Dog Swallowing A Fish (item number EA 13596) dated to the late 18th Dynasty c. 1350-1300 BCE. The statue shows a puppy "wearing a collar which shows traces of gilding, with lop ears and a long bushy tail which curls around its hind quarters" and "adopts the well-known posture of a dog at play with front legs bent and rump raised in the air" (British Museum, 237). The dog holds a small bronze object in its mouth which has been interpreted as either the tail of a fish or a large fly it is playing with. The piece is carved from tusk with the bronze attachment glued in place on the mouth and two holes in its base which most likely held the statue to a wall. The British Museum observes:

The piece is brilliantly observed and belongs to a class of small carvings made towards the end of the 18th Dynasty which portrays animals that were familiar to and beloved by the Egyptians. It can have been made for no other purpose than to delight and amuse its owner. (237)

Dogs & Anubis

Indeed, dogs were familiar and loved by the Egyptians. This devotion is clear from the number of times they are depicted and referenced in art and inscriptions throughout the history of the civilization and the way they were generally treated.

As already noted, dogs were depicted on palettes in the Pre-Dynastic and Early Dynastic periods. During the Old Kingdom, the dog of king Khufu (2589-2566 BCE), Akbaru, was said to have been buried in the king's tomb with him. One of the best known dogs of Egypt was given his own funeral stele in this same era. Abuwtiyuw was the dog of a servant of the king (though which Old Kingdom monarch is unclear) who was honored with a burial fit for a noble. The dog's stele reads:

The dog which was the guard of His Majesty. Abuwtiyuw was his name. His Majesty ordered that he be buried ceremonially, that he be given a coffin from the royal treasury, fine linen in great quantity, and incense. His Majesty also gave perfumed ointment and ordered that a tomb be built for him by the gangs of masons. His Majesty did this for him in order that he [the dog] might be honored before the great god, Anubis. (Hobgood-Oster, 41-42)

The Basenji is the most often cited as the inspiration for the image of Anubis, one of the principal gods of the dead who guided the soul to judgment in the afterlife (although the Greyhound, Pharoah, and Ibizan are also contenders). Anubis is often referred to as "the jackal dog" but this is not how he was known to the ancient Egyptians where he is always referenced as a dog as in his epithet "the dog who swallows millions". It should be noted, however, that the Egyptians did not distinguish between the jackal and the dog, especially so with pariah dogs.

The town of Hardai was the cult center of Anubis and so was called Cynopolis ("City of the Dog") by the Greeks. Here dogs freely roamed through Anubis' temple and were also bred for sacrifice. Mummified dogs were brought to the temple as offerings to Anubis (the "red dog", identified with the Pharaoh breed, being preferred) but the death rate of the temple dogs was not high enough to meet the demand for mummified sacrifices. A kind of puppy mill was initiated for the sole purpose of breeding dogs for sacrifice to Anubis.

Dogs, Collars, & the Afterlife

Under ordinary circumstances, however, killing a dog carried severe penalties and, if the dog was collared and clearly owned by another, its murder was a capital crime. The death of a family dog elicited the same grief as for a human and the family members would shave their bodies completely, including the eyebrows. As most Egyptian men and women shaved their heads to avoid lice and maintain basic hygiene, the absence of the eyebrows was the most notable sign of grief. In some periods the opposite was observed and people would not shave at all.

Even so, just as with the mourning of the death of a human being, it was believed that one would meet one's canine friend again in the afterlife. Tomb paintings of the pharaoh Tutankhamun show him in his chariot with his hunting dogs and Rameses the Great is depicted similarly. As in the case of Khufu and his companion, dogs were often buried with their masters in order to accompany them closely in the afterlife. Some dogs seem to have been killed after the death of their master and then mummified while others died earlier and still others, as at Cynopolis and perhaps at Saqqara, were ritually sacrificed.

As in many other cultures, earlier and later, the dog was seen as a kind of intermediary between worlds who could act as a guide; this is most clearly seen in the image of the dog-god Anubis. The dog who aided and guided one in life would serve the same purpose in the afterlife. The intimate relationship between dogs and their masters in Egypt is made clear through inscriptions in tombs, monuments, and temples and through Egyptian literature. Dogs, unlike cats, were always named and these names were inscribed on their collars. Dunn writes:

We even know many ancient Egyptian dog's names from leather collars as well as stelae and reliefs. They included names such as Brave One, Reliable, Good Herdsman, North-Wind, Antelope and even "Useless". Other names come from the dog's color, such as Blacky, while still other dogs were given numbers for names, such as "the Fifth". Many of the names seem to represent endearment, while others convey merely the dog's abilities or capabilities. (Dunn, 2)

These dog collars most likely began in the early periods as simple rope, probably similar to the slip-leads used today, but evolved over time into intricate works of art. Already by the Old Kingdom the collar was a thick leather ring glued together and pulled over a dog's head. During the Middle Kingdom these collars became more elaborate and were often adorned with copper and bronze studs. In the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) the dog collar reached its height with gold and silver collars inscribed with the dog's name.

Two particularly interesting pieces from this period come from the tomb of Maiherpri, a noble during the reign of Thutmose IV (1400-1390 BCE), whose name translates as "Lion of the Battlefield" and so was obviously regarded as a great warrior. In addition to his quiver, wrist guards, and arrows in the tomb were two dog collars which are dyed pink and intricately adorned with images. One is ornamented with images of lotus flowers and horses punctuated by brass studs while the other depicts dogs hunting ibex and gazelle and includes the name of the dog, Tantanuit, which suggests this dog was female as "Tantanuit" was a woman's name.

Leashes, throughout Egypt's history, were either leather or papyrus rope. A dog collar excavated from a grave in modern Sudan at the site of the necropolis of Tombos, dated to the New Kingdom, is a leather band with a diamond-shaped terminus which was fitted into a slit cut in the collar; the remaining length of the leather was then used as a leash.

The devotion of people to their dogs, and the affection the dogs returned, continued in the afterlife where it was believed one found all that had seemingly been lost at death. Once the soul had been justified by Osiris and allowed to move on, one would travel to the Field of Reeds which was an idealized version of the life one had left behind on earth. All of the loved ones who had gone on before would greet the soul as it stepped into this realm and there would be the same house, the garden, the stream one had enjoyed in life and, with them, souls would again find their favorite dog faithfully awaiting their arrival home.