Considering the value the ancient Egyptians placed on enjoying life, it is no surprise that they are known as the first civilization to perfect the art of brewing beer. The Egyptians were so well known as brewers, in fact, that their fame eclipsed the actual inventors of the process, the Sumerians, even in ancient times.

The Greeks, who were not great fans of the drink, wrote of the Egyptian's skill while largely ignoring the Mesopotamians. The Greek general and writer Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE), however, gives a critique of the Mesopotamian version he sampled in the region of Armenia in his Anabasis, noting, "the beverage without admixture of water was very strong, and of a delicious flavour to certain palates, but the taste must be acquired" (4.5.27).

The Mesopotamian brew in Xenophon's narrative was served in great bowls, and one drank it through a straw to avoid the malt floating on the surface, which was the usual manner of drinking beer in Mesopotamia. The straw, in fact, was invented by the Sumerians specifically for drinking beer. Mesopotamian beer was thick, the consistency of modern porridge, and could not just be sipped.

The Egyptians altered the Sumerian brewing methods to create a smoother, lighter, brew which could be poured into a cup or glass for consumption. Egyptian beer, therefore, is most often cited as the 'first beer' in the world because it has more in common with the modern-day brew than the Mesopotamian recipe, even though few modern-day beer enthusiasts would recognize the ancient brew as their favorite drink.

The Drink of the Gods

Beer was among the many gifts of the gods granted to humanity in the early days of the world. According to the myth, the god Osiris himself gave humanity the gifts of culture and taught them the art of agriculture; at this same time, he also instructed them in the craft of brewing beer. No actual single story relates this event, however, and the origin of beer in Egypt is often - inaccurately - given as the story known as The Destruction of Mankind. However, this story, which dates from the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE), makes clear that beer was already known to the gods. No mention is made of the gods creating alcohol in the tale - it is a given that it already exists - they simply find a good use for it.

In The Destruction of Mankind, which forms part of the text of the Book of the Heavenly Cow, the great god Ra becomes outraged when he hears of a plot by humanity to overthrow him and decides to destroy everyone on earth. He sends his daughter, the goddess Hathor, to take care of this task for him and seems quite pleased as she rampages from one community to the next, tearing people apart and drinking their blood. As she kills more and more people, she transforms into the savage avenger Sekhmet and her path of destruction grows larger. Ra repents of his decision and the other gods point out to him that if Sekhmet persists, there will be no humans left to offer sacrifices or worship to the gods and, further, none to pass on the lesson Ra's punishment was to teach.

Ra wants to call Sekhmet back, but she is consumed with bloodlust and there seems no way to stop her. Ra, therefore, commands that a large quantity of beer be dyed red and delivered to Dendera, directly in Sekhmet's path. The goddess finds the beer and, thinking it blood, drinks it. She then becomes drunk, falls asleep, and wakes again as Hathor, the kind and gentle friend of humanity. The Tekh Festival, one of the most popular in Egypt, commemorated this event.

The Tekh Festival was known as 'The Festival of Drunkenness' and was first observed in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) but may have had earlier origins. It was most popular during the New Kingdom where the story of Sekhmet's rampage and transformation has been found carved in the tombs of Seti I, Ramesses II, and others. At this festival, which was dedicated to Hathor, participants would drink to excess, fall asleep in a certain hall, and wake suddenly to the beating of drums.

The alcohol would lessen people's inhibitions and critical faculties and allow for a glimpse of the goddess when participants were awakened by the drums. There seems to have also been a sexual side to the festival as, according to Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown, some scenes of the celebration on temple walls "link drunkenness with 'travelling through the marshes', a possible euphemism for sexual activity" (169). This would hardly be surprising since sex was not only considered a natural aspect of human life but was also associated with Hathor and Mut, a fertility goddess who was also closely linked to the festival.

Beer is mentioned as a part of almost every major festival in ancient Egypt and was often supplied by the state, as in the case of the Opet Festival and the Beautiful Feast of the Wadi. The festivals of Bastet, Hathor, and Sekhmet, especially, all involved vast quantities of beer and encouraged drinking to excess. Graves-Brown writes:

While drinking was often discouraged in ancient Egypt, at times it appears to have been celebrated by both sexes. An ancient Egyptian tomb painting shows an elite woman vomiting through overindulgence in alcohol. A woman at a drinking party asks for 18 cups of wine because her throat is a dry as straw. (3)

Although beer was enjoyed at these celebrations, it was certainly not reserved only for special occasions. Beer was a staple of the Egyptian's daily diet as well as a common form of compensation for work and frequently prescribed for one's health.

Beer in Daily Life

Women were the first brewers in Egypt. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick writes, "both brewing and baking were activities undertaken by women and numerous statuettes found in tombs show women grinding grain in mills or sifting the resulting flour" (408). Beer was first brewed in homes by women and only later became a state-funded industry presided over by men.

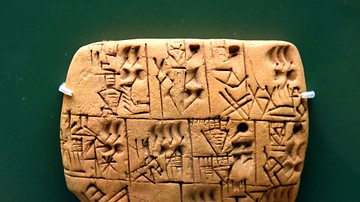

The early feminine influence on brewing is perhaps indicated in the deity who presided over the craft: Tenenet (also Tenenit, Tjenenet) the goddess of beer. Like the goddess Ninkasi of the Sumerians, Tenenet watched over brewers and made sure that the recipe was observed for the best quality beer. The Sumerians had the Hymn to Ninkasi, which was basically the recipe for beer sung by brewers so they would memorize it, but no evidence of a similar song has been found in Egypt.

The ancient Egyptian brewers do not seem to have suffered much from this, however, as their product was immensely popular. The common name for beer was heqet (also given as hecht and henket) or tenemu (giving the goddess Tenenet her name), but there were also names for specific types of beer. Beer was classified according to alcoholic strength and flavor, with the average beer having an alcohol content of 3-4% while beer used in religious festivals or ceremonies had a higher alcohol content and was considered of better quality.

Men, women, and children all drank beer as it was considered a source of nutrition, not just an intoxicant. Beer was regularly used as compensation for labor (referred to as hemu) and workers at the Giza plateau, for example, were given beer rations three times a day as payment. Records of payment through beer at various sites throughout Egypt, in fact, provides some of the best evidence that the great monuments were not built by slaves but by paid Egyptian labor.

Beer was also frequently prescribed in medical texts. Over one hundred recipes for medicines included beer, and even when beer was not included in the list of ingredients, it was suggested that a patient take the prescription with a cup of beer which was thought to "gladden the heart." Beer was also thought to confuse the evil spirits which were considered the cause of many diseases. A spell given to cure one unnamed disease directs the person to call upon the god Set who will empower the beer so that the spirits become perplexed and disoriented and will leave the body. Precise recipes for these brews were never written down, but the general method used is fairly clear from both texts and small models of brewers found in tombs.

Brewing & Banquets

The best-known examples of these models come from the tomb of Meketre of the early Middle Kingdom. These are small dioramas which detail the brewing process at that time. The models supplement letters, receipts, and other written works in depicting how beer was brewed and by whom. Strudwick notes that "although beer was produced daily in most ancient Egyptian households, there was also large-scale production in breweries for distributing rations to town-dwellers, taverns or 'beer houses', wealthy individuals, and state employees" (410).

Every brewer had her or his own particular specialty, with some brews known for higher alcohol content and others for a certain flavor. According to Strudwick, "the most common kind of beer was a rich, slightly sweet ale, rather like brown ale, but lighter beers similar to a modern lager were created for special occasions" (411). In either case, as in the modern day, brewers followed basically the same procedure.

At first, around the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, beer was brewed by mixing cooked loaves of bread in water and placing the mixture in heated jars to ferment. The use of hops was unknown to the Egyptians as was the process of carbonation. To a modern-day beer drinker, an Egyptian brew would taste more like a fruit drink than the familiar beverage. Dates and honey were added for sugar, taste, and higher alcohol content, and then yeast in order to increase fermentation. This beer was a thick, dark red brew which perhaps suggested the beer originally dyed by Ra to calm and transform Sekhmet.

By the time of the New Kingdom barley and emmer (wheat) were used which were mixed with water to create a mash which was then poured into vats and heated to ferment. This mixture was then strained and different herbs and fruits added for the flavoring of the various types of beer. According to Strudwick, "fermentation of everyday beer took a few days, producing a mixture fairly low in alcohol" and "the outcome was a thick, brothy liquid that had to be filtered through a basket before being drunk" (410). Once strained, the beer was sealed in ceramic jugs and stored, often underground in a process similar to later lagering.

In the New Kingdom, when emmer and barley were used, the use of dates and honey decreased in the production of common beer and were only used for higher quality brews for special occasions. Beer with a high alcohol content was favored for banquets and festivals and, in fact, a party was rated a success depending on the level of the participants' intoxication and the amount of beer consumed. The highest quality beer, of course, was brewed for the king and the nobility and flavored with honey which was associated with the gods. The beer found in the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, for example, was honey beer similar to the later European mead.

From the Middle Kingdom onwards, beer was increasingly a state-run industry, although people still brewed their own in their homes. This beer continued to be amber in color but not as thick; as shown by residue found in the bottom of vats and also through the beer found in Tutankhamun's tomb and others. Just as beer was considered a staple for Egyptians in life, so was it considered a necessary offering for the dead; beer, therefore, became one of the most common grave goods placed in tombs for those who could afford to part with it. Since beer was was a common form of payment, including jars of the brew in a tomb would be comparable to burying one's paycheck with the deceased.

Besides the use of beer as part of one's daily meals and at festivals, the drink featured prominently at banquets and funerals. Funerals were a celebration of the life of the departed and also a send-off for the soul on the continued journey into the afterlife. Once the formal ritual of the funeral was concluded, family and guests would gather, often outside the tomb under a tent, for a picnic-banquet at which the food the deceased had enjoyed in life would be served along with a quantity of beer and, sometimes, wine.

Beer was served to guests from pitchers and poured into ceramic cups from which guests drank without the use of straws or strainers. Strudwick notes that "the quality of beer depended on both the skill of the brewer and the sugar content: the more sugar that was added to the fermentation, the stronger the beer" (411). The beer served at funerals would have been higher in alcohol content than a regular brew. The same beer enjoyed by the guests would have earlier been placed in the tomb of the departed.

Just as beer was offered to the souls of the dead, it was considered the best offering to the gods. Temples brewed their own beer which was given to the statue of the god in the inner sanctum to gladden his or her heart just as it did humanity's. Food and drink would be placed before the deity's statue, which contained their spirit, and the nutrients absorbed supernaturally. The meal would then be taken away and given to the temple staff. Osiris had given the people the knowledge of beer, and the people showed their gratitude by offering in return the fruits of that knowledge: beer, the drink of the gods.