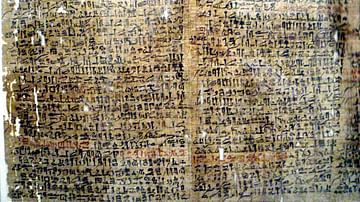

The Westcar Papyrus, dated to the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (1782 - c.1570 BCE), but most likely written during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), contains some of the most interesting tales from ancient Egypt. The papyrus takes its name from the man who first acquired it, Henry Westcar, who purchased the piece c. 1824 CE. Westcar never disclosed how he came into possession of the scroll nor where, and so no one knows in what context it was found or its original location.

The scroll was later purchased or otherwise acquired by the Egyptologist Karl Lepsius c. 1839 CE, who understood only parts of it, and then was finally translated into German in 1890 CE by Adolf Erman. Erman's translation then became the standard on which later scholars would rely. It was Erman who first called the stories in the papyrus 'fairy tales,' and that definition has stuck. It is also apt in that the four stories the papyrus contains all revolve around magical and fantastic events.

There were originally five stories in the manuscript but the first is missing (and, according to some scholars, so is the conclusion of the papyrus). It is assumed that the work began with some kind of invitation by Khufu to his sons to tell stories about great wonders of the past or perhaps it was a competition among the sons to tell the best kind of story. This is, of course, speculation as no internal evidence in the texts suggests its beginning.

Based on the concluding lines of the first story, it told of some great wonder that happened in the time of King Djoser (c. 2670 BCE) and most likely involved his architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE). The section of the tale which is preserved is a set piece which also appears in the next two stories in which Khufu approves of the tale told and decrees an elaborate sacrifice be made to the people in the story.

The Wax Crocodile

The second tale is usually translated as The Marvel Which Happened in the Time of King Nebka. Nebka is a mysterious figure in ancient Egyptian history who may have reigned in the 3rd Dynasty (c. 2670-2613 BCE). Egyptologists still cannot agree on who he was or when he ruled. Many consider him synonymous with an early king named Sanakht who may have founded the 3rd Dynasty, but this is disputed. Other scholars place Nebka toward the end of the 3rd Dynasty, just before Huni, the last to rule before the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

The Westcar Papyrus is one of the few documents from ancient Egypt to mention Nebka. His placement in the work, following Djoser, makes sense if he were the ruler who preceded Huni but not if he was the founder of the 3rd Dynasty.

This tale is told by Khafre (Khufu's successor) and is usually translated as The Wax Crocodile. In the story, Nebka is on his way to the Temple of Ptah at Memphis and stops at the home of a priest and scribe named Webaoner. Webaoner's wife notices a handsome youth in the king's entourage and sends him a gift, and he responds by asking to spend some time with her in the pavilion on the estate's grounds. The wife orders the caretaker to prepare the pavilion for them, and they spend the day there drinking, feasting, and having sex. Afterwards, the youth goes and bathes in the nearby lake.

The next morning, the caretaker feels it his duty to tell his master of what had happened, and Webaoner calls for his chest of magic herbs and spells and creates a wax crocodile. He tells the caretaker to cast it into the lake behind the youth the next time he bathes there. Later that day, the wife again summons the caretaker to prepare the pavilion for herself and her lover and, when they are done, the youth goes down to the lake for a bath. The caretaker drops the wax crocodile into the water and it instantly becomes a live creature over twelve feet long who grabs the young man in its jaws and vanishes beneath the surface.

Nebka stays at the estate for seven days until, just as he is ready to depart, Webaoner tells him he must see for himself what has happened. He brings the king to the lake and calls out to the crocodile to bring the youth back. The crocodile appears with the young man in his mouth and drops him on the shore. Nebka is startled by the creature, but Webaoner reaches down and touches it and it becomes a wax figure again. He then tells Nebka about the affair between the youth and his wife and Nebka says to the crocodile, "Take what belongs to you!" Webaoner touches the crocodile again, and it comes back to life, grabs the youth, and leaps into the water. Nebka then orders that the adulterous wife be burned at the stake and, afterwards, has her ashes thrown in the river.

When Khafre finishes his tale, Khufu declares it good and orders sacrifice made in the honor of Nebka and Webaoner.

Sneferu & the Green Jewel

Khufu's son Bauefre speaks next, telling a story about king Sneferu (c. 2613-2589 BCE), Khufu's father. In the tale, Sneferu is depressed and has been wandering around his palace looking for some diversion to lighten his mood. His chief priest, Djadjaemonkh, suggests, "Let Your Majesty proceed to the lake of the palace and equip for yourself a boat with all the beauties who are in your palace chamber. The heart of Your Majesty shall be refreshed at the sight of their rowing as they row up and down."

Sneferu is delighted at this suggestion and issues his command:

Let there be brought to me twenty oars made of ebony, fitted with gold, with the butts of sandalwood fitted with electrum. Let there be brought to me twenty women, the most beautiful in form, with firm breasts, with hair well braided, not having opened up to give birth. Let there be brought to me twenty nets, and let these nets be given to these women when they have taken off their clothes.

When all this is done, Sneferu goes out on the lake with the women and "the heart of His Majesty was pleased at the sight of their rowing" until one of them loses a fish-shaped jewel from her hair and stops rowing. The other women stop as well and Sneferu asks what the matter is. The woman tells him how she has just lost her jewel and he says it is no matter, he will give her another. The woman ways, "I prefer what is mine to another" and so the king summons Djadjaemonkh, who is on the boat, and tells him the problem.

Djadjaemonkh then recites a magic spell and parts the water, placing "one side of the water of the lake upon the other" and retrieves the jewel. Just as Moses will later do with the Red Sea in the famous story from Exodus, once the jewel is returned to the woman, Djadjaemonkh allows the waters to fall back into place. Sneferu is pleased and rewards the priest and goes on enjoying his day on the lake. When the story concludes, Khufu again orders that sacrifices be made to Sneferu and Djadjaemonkh.

Khufu & the Magician

The prince Hardedef now stands up and says to Khufu, "You have heard examples of the skill of those who have passed away, but there one cannot know truth from falsehood. But there is with Your Majesty, in your own time, one who is not known to you." He then tells his father about a magician named Djedi who is over 100 years old, eats 500 loaves, a shoulder of meat, drinks 100 jugs of beer and knows how to reattach a head which has been severed from a body and make the person live again as well as perform other miracles and wonders. Hardedef also claims that Djedi knows the number of shrines of the enclosure of Thoth, something Khufu has been interested in finding out. Khufu is intrigued and sends Hardedef to fetch this man.

Hardedef finds Djedi and requests he return with him to the palace. The story details the trip with Djedi's family and his request for a boat for his books, and they finally arrive at the palace. Khufu is anxious to see the feat of reattaching a head which has been severed and sends for a prisoner to be brought, but Djedi says he cannot perform this on a human being because it is against the will of the gods. A goose is brought instead and its head cut off. The body is placed on one side of the hall and the head on the other and the two move toward each other, the goose's body waddling headless and the head cackling until they join again and the goose is whole. This same is then done with a waterfowl and an ox.

Khufu is well pleased and then says how he has heard that Djedi knows the number of shrines in the enclosure of Thoth, but Djedi claims he does not, he only knows where they are kept. When Khufu asks him to bring them, he says he cannot because it is written that only the eldest son of Reddedet will be able to bring them. When Khufu asks who Reddedet is, he is told that she will bear three sons who will hold high office in the land and replace Khufu's line. Khufu is upset to hear that his own sons will not inherit the throne but is assured that they will rule and, only after one of his sons (Khafre) and then his son (Menkaure), will the son of Reddedet come to the throne.

Unlike the earlier tales, this one does not end with the set piece of the king commanding sacrifices but rather with him setting Djedi up with an allowance and a place to live with Hardedef. The story prepares a reader for the last of the five in which the sons of Reddedet will be born.

Khufu and the Magician is often cited by scholars (such as Barbara Watterson) as depicting the king as callous and insensitive. It has also been claimed that the Westcar Papyrus may have influenced the later view (famously expressed by Herodotus) that Khufu was a cruel monarch and despised by the people. Nothing in the text would indicate this kind of conclusion. Khufu calls for the prisoner to be brought because he expects Djedi will be able to reattach the severed head and, even if he should fail, the man would be executed anyway. How certain scholars have concluded that the story presents Khufu poorly is unclear since the prisoner episode is the reason most often cited.

The Birth of the Kings

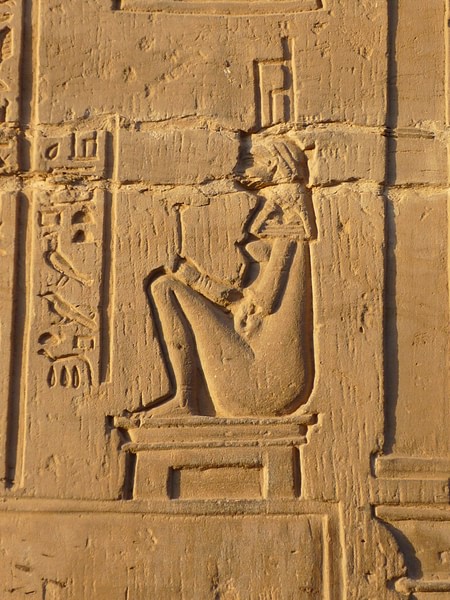

The last story has no narrator and is given in the third person. It tells the tale of the magical birth of the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty: Userkaf, Sahure, and Kakai. Reddedet, wife of a priest of Ra, goes into a difficult labor, and the god Ra, hearing it, sends Isis, Nephthys, Meskhenet, Heket, and Khnum to help her. These deities transform themselves into dancing girls and musicians and go to the home where they find Reddedet's husband, Rewosre, upset over his wife's condition. They ask him if they can help since they know about childbirth, and he tells them to proceed.

The story then details the births of the three kings and is thought to depict actual childbirth in ancient Egypt and the role of midwives: "they entered into the presence of Reddedet. Then they locked the room on her and on themselves. Isis placed herself in front of her, Nephthys behind her, and Heket hastened the childbirth." Isis speaks to the child, and it is born, washed, and umbilical cord cut; he is then placed on a cushion. The births of the next two boys are described in the same way only each time Isis gives the boys their name with a slightly different spell.

After the children are all born safely the goddesses emerge from the room and Rewosre thanks them and offers them a sack of grain for making beer. The deities leave when Isis suddenly says to the others, "What is this, that we are returning without performing a marvel for these children?" and so they fashion three royal crowns and put them in the sack of grain. They then cause a huge storm to blow up as an excuse and return to the house, asking if they can leave the grain there so it will not get wet. They say they will retrieve it on their journey back, and the sack is placed in a locked room.

Reddedet recovers from the births after 14 days and calls for her maidservant to see if the house is purified and prepared for a feast. The maid says that everything is ready except the beer because there is no grain in the house except what Rewosre gave to the musicians and dancing girls who helped with the births. Reddedet tells her to use it and Rewosre will replace the bag before the girls return.

When the maid goes into the room, though, she hears music and the sounds of dancing and celebration coming from nowhere and runs to tell Reddedet. When the lady of the house goes to the room, she discovers the sounds are coming from the sack of grain and there are three royal crowns inside for her sons. She is overjoyed at their good fortune and tells her husband, but they lock the sack up in a chest and seal it in a room in fear that Khufu might learn of the future kings and not be pleased.

A few days later, Reddedet has an argument with her maid and beats her. The girl is upset and runs out of the house after yelling that she will go to the king and tell him what is in the chest and what it means. She is on her way when she passes by her brother, another servant in the house, who is threshing flax. When he asks her where she is going in such a state, she tells him the whole story. The brother is outraged that she would treat her mistress in this way, betraying her trust, and beats her with a whip of flax. The girl runs to the river to get a drink of water but is seized by a crocodile and eaten.

The brother goes to tell Reddedet the news and finds her sitting sadly. When he asks what is wrong, she tells him about how she had a fight with his sister who has gone off to denounce her to the king. The brother assures her all will be well because his sister has been taken by a crocodile, and at this point, the story ends.

It was originally thought that the manuscript broke off after this scene, since the scroll is divided into sections and, just as the beginning is missing, so the conclusion was thought to be. According to a number of scholars, however (Lichtheim, Verner, and Lepper among them), the manuscript is complete as it stands save for the obvious loss of the first story. The manuscript concludes leaving the reader with the understanding that the secret of the three boys who will grow up to become rulers of Egypt, ending Khufu's line, will remain safe with their mother and the 5th Dynasty will continue the glory of Egypt.