Among the most engaging and influential works from Egyptian literature are the stories in the cycle known as Setna I and Setna II or The Tales of Prince Setna. These are fictional works from the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), the Ptolemaic Period (323 -30 BCE), and Roman Egypt (30 BCE-646 CE).

The works feature Prince Setna Khamwas as the main character in Setna I and as an important secondary character and foil to his son in Setna II. As with any great works of literature, these pieces can be interpreted in many different ways, but their primary purpose was to entertain while teaching important cultural and religious lessons.

The stories have influenced many later writers and important works of literature. Herodotus cites Setna as the high priest Sethos in one of his best-known passages regarding the troops of the Assyrian king Sennacherib defeated by mice who gnaw through their equipment while they sleep (Histories II. 141). This passage is his version of the story told in the biblical book of II Kings 19:35 in which an angel of the Lord destroys the Assyrian army laying siege to Jerusalem. The sequence from Setna II in which Setna and his son Si-Osire travel to the underworld draws upon Greek mythology and influences later Christian scripture in the story of the rich and poor man in the afterlife.

In the Setna tale, the rich man suffers in the afterlife for his misdeeds on earth while the poor man is rewarded for maintaining the concept of ma'at (harmony and balance). In the biblical Book of Luke 16:19-31 this same theme is explored through the Rich Man and Lazarus story. Here, a rich man who seems to expect a reward in the afterlife is punished while the poor beggar Lazarus is rewarded in heaven for his suffering on earth.

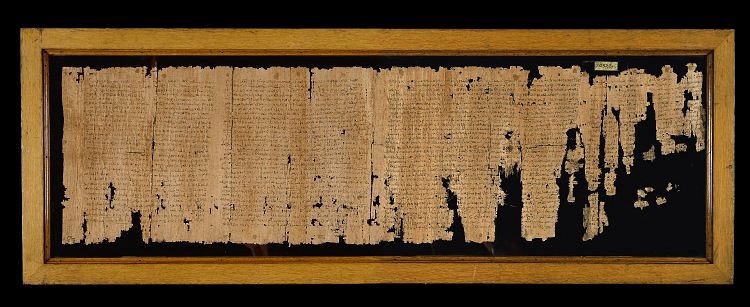

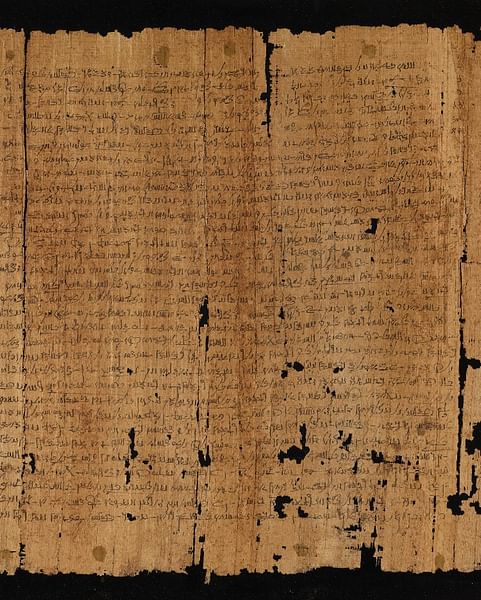

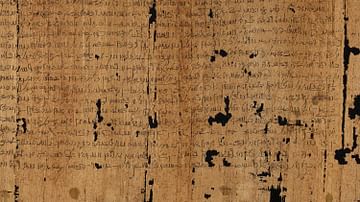

It is hardly surprising that the Setna tales would influence other works as they seem to have been quite popular in their time as copies and fragments of copies exist. The two primary sources of the texts are papyrus scrolls, written in demotic script, presently housed in the Cairo Museum in Egypt (Setna I) and the British Museum in London (Setna II). The beginning of Setna I is damaged but has been reasonably reconstructed using fragments elsewhere and context clues from the intact section of the scroll.

Historical Basis for the Tales

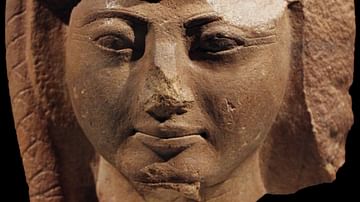

The Setna stories are based on the historical figure of Khaemweset (c. 1281 - c. 1225 BCE), the fourth son of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE). Khaemweset was High Priest of Ptah and responsible for the upkeep of the temples of Egypt. He went further in his duties than any before or after him, however, in restoring temples and monuments which had fallen into ruin and making sure the original owners' names were inscribed on them. It is due to these efforts that he is remembered as 'the first Egyptologist' in that he studied and preserved the past.

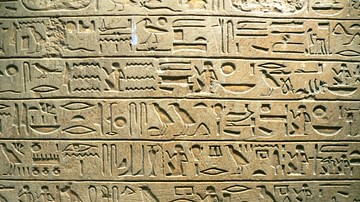

Khaemweset was well known for entering tombs for preservation work and for his ability to understand ancient inscriptions. By the time the Setna stories were written, he was venerated as a great magician and sage and these aspects of Khaemweset's figure feature prominently in the persona of Prince Setna, whose name is derived from a corruption of Khaemweset's priestly title of Sem or Setem Priest.

Khaemweset's penchant for entering other people's tombs without concern as well as his ability to read Old Kingdom inscriptions are developed in Setna I as the main character enters a tomb to retrieve a magical book. Even though Khaemweset was highly regarded, this practice of venturing into tombs was not, and Prince Setna is presented as a man heedless of the consequences of his actions, who impulsively follows his heart instead of the precepts of tradition and cultural values.

Setna I

The story of Setna I (also known as Setna Khaemuas and the Mummies or Setne Khamwas and Naneferkaptah) begins with Prince Setna Khamwas, son of Ramesses II, searching for an ancient tomb along with his foster brother Inaros. The tomb is supposed to contain an ancient magic book, but when he enters it, he is confronted by the ghosts of the family: Naneferkaptah, his wife Ahwere, and their son Merib. Ahwere tells Setna he cannot have the book because it is theirs; all three of them died for it.

She then tells him the story of how Naneferkaptah, a great scribe and magician, stole the book, which was handwritten by the god Thoth himself, from a secret hiding place in the sea and Thoth, enraged, drowned first her son, then herself, and Naneferkaptah then drowned himself in grief. Setna does not care and says he will take the book but is then challenged to a game by Naneferkaptah which he loses each time they play. He calls out to Inaros, outside the tomb, to bring him his magic amulets, escapes from the clutches of Naneferkaptah, and steals the book.

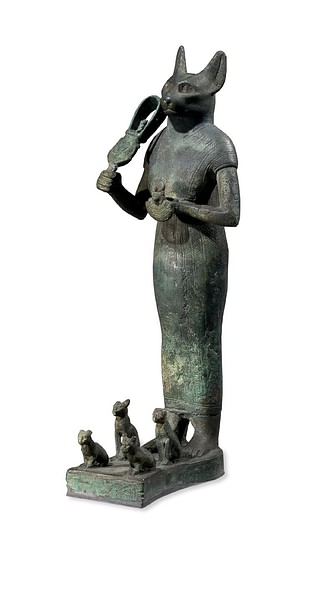

Naneferkaptah swears to Ahwere that he will have the book back, and then the scene switches to Memphis where Setna is walking on the street when he sees a beautiful woman and lusts after her. He sends a servant to ask if she will spend an hour with him, but the woman, a daughter of the priest of Bastet named Taboubu, instead invites him to her home in Bubastis.

Setna travels there and, in his desire, promises her anything to sleep with her. She has him sign over his home and worldly possessions, then has his children brought so they can witness the transaction legally, and then has the children killed and their bodies thrown into the street for the dogs to eat. Setna, in a trance of lust, is not disturbed by any of this and only wants her more, but when he finally moves to embrace Taboubu, she screams and vanishes. Setna finds himself naked on the street with his penis thrust into a clay pot.

As he is standing there, Pharaoh passes and tells him that everything that transpired was a dream and his children and possessions are all safe and intact. He warns Setna to return the book to Naneferkaptah and make restitution. Setna goes back to the tomb with the book and then travels to Coptos, where Ahwere and Merib are buried, and brings their mummies back to the necropolis of Memphis to be reunited in the tomb with Naneferkaptah. The tomb is then sealed so the book will not be found again and the story ends.

Setna II

The second Setna tale (also known as Setna and Si-Osire) opens with Setna's wife, Mehusekhe, praying for a child in the temple. Her prayers are answered, and she gives birth to a son whom the gods have already told Setna should be named Si-Osire. Si-Osire grows quickly, seeming to age in body and in mind much faster than he should. In only a few years he is mature and among the wisest scribes in the land.

One day, his father comments on a funeral procession of a rich man who is followed by many mourners and that of a poor man who has none, stating how the rich man must be so much happier. Si-Osire corrects his father's impression by taking him to the underworld. There they see people who were unfortunate in life, continuing this same trend as they try to plait ropes together, but before they can finish, donkeys chew through their work. There are others they pass who reach for food and water above them, but before they can get to these, others are digging trenches at their feet to prevent them. These people, Si-Osire explains, are those who were grasping in life and so continue to be in death.

They pass by a man crying loudly, crushed in the pivot of a door, and then see a rich man dressed in fine garments standing near Osiris in the hall of judgment. Si-Osire points out that this is the poor man whose funeral they saw earlier, who is now rewarded for his good deeds on earth. The crying man in the doorway is the rich man who engaged in many misdeeds on earth and now must pay for them in the afterlife. Si-Osire explains: "He who is beneficent on earth, to him one is beneficent in the netherworld. And he who is evil, to him one is evil. It is so decreed and will remain so forever" (Lichtheim, 141). Si-Osire then leads his father back to the land of the living.

In the second part of the story, Si-Osire is a grown man when, one day, a Nubian sorcerer comes to the court with a scroll strapped to his body and issues a challenge: if no one in the court can read this scroll without breaking its seal and opening it, he will return to his country and tell everyone there of the shame of Egyptian sages. Pharaoh calls instantly for Setna and asks his advice, but Setna has no idea and asks for ten days in which to deal with the problem. He is granted the time but cannot find the answer to the riddle and becomes depressed.

Si-Osire gets him to talk about his problem and tells him that he can solve it. He shows his power by having his father go downstairs in the house and hold up a book which Si-Osire, obviously, cannot see; but the young man is still able to call out exactly what the book is and its contents. Setna brings the boy to court where he faces the Nubian sorcerer and is able to speak the contents of the scroll. The scroll's story is about Nubian treachery and how a sage named Horus-son-of-the-Nubian-woman battled an Egyptian magician named Horus-son-of-Paneshe. The Egyptian magician prevails, and the Nubian sage is banished from Egypt for 1,500 years. In the end, it is revealed that the Nubian sorcerer is the sage Horus-son-of-the-Nubian-woman from the scroll and Si-Osire is the reincarnation of Horus-son-of-Paneshe who came back to earth just for this purpose: to save Egypt and defeat his ancient enemy.

Si-Osire then destroys the Nubian sorcerer and his mother, who has come to his aid, with magical fire. As the flames consume them, Si-Osire disappears, the flames go out, and the court is as it was before. Setna loudly laments the loss of his son, but the pharaoh consoles him in telling him his son saved Egypt and will always be honored. The story ends with Mehusekhe again praying for a child and becoming pregnant. The couple have another son whom they love, but Setna never forgets Si-Osire and provides his soul with offerings for the rest of his life.

Commentary

Setna I, besides being an entertaining adventure story, conveys a number of important cultural values. Tombs were considered the eternal homes of the dead and tomb robbing was a very serious crime. Execration texts, better known today as 'curses' were often inscribed along with one's autobiography on tomb walls, promising vengeance on any who would desecrate or steal from the deceased. The fact that Setna, identified as a prince, a scribe, and a magician, is punished for this sin would have made it clear that no one is exempt from eternal justice, and those of lesser status could expect even worse treatment.

The story-within-a-story of Naneferkaptah and his family illustrates the danger of stealing from the gods. Naneferkaptah is a proto-Setna in the story, a prince, sage, and magician who disregards cultural values and wisdom to take what he knows he has no right to. He is punished with the deaths of the people he loves most and then loses his life as well. Both men are magicians, and in Setna I and Setna II magic is an important element, just as it was in Egyptian culture; but Setna I shows how even a skilled magician, learned in his craft, can make a terrible choice in desiring what he has no right to.

Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch has noted that the section of the story about Setna and Taboubu can be interpreted along these same lines but as direct punishment by Bastet for Setna's crime of lust. Setna never sees Taboubu as an individual, as a person, but only as a sex object. Pinch points out how Bastet, as protectress of women, children, and women's secrets, would have been quick to punish a man for treating a woman so poorly. Women were highly regarded throughout Egypt's history and Bastet was among the most popular deities.

The author's choice of Taboubu as the daughter of a priest of Bastet invites this interpretation. This section is also thematically linked with the tale of Naneferkaptah and his family in trying to have what is not one's right. Taboubu repeatedly reminds Setna in the story that she is a woman of high birth, associated with the clergy of Bastet, and should be treated with respect; each time Setna only urges her to finish up whatever she needs to do so he can have sex with her.

In the end, all wrongs are righted as Setna repents of his action, returns what does not belong to him, and makes restitution by reuniting the family's mummies in the tomb. Setna II then continues the story with the prince as a married man, whose other children are perhaps grown and have moved on, and how he is rewarded with a savior son.

Setna II is an especially interesting piece in that it contains a number of Greek elements in its depiction of the afterlife and also relies heavily on the concept of reincarnation. Throughout most of Egypt's history, the afterlife was viewed as a continuation of one's journey on earth. Once one died, one stood in judgment before the divine tribunal and then, hopefully, was justified and went on to an eternal paradise which perfectly mirrored one's time on earth. In certain periods, such as the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, this view was questioned but it remained fairly constant and even in that era was still accepted.

There was another view, however, concurrent with this one, which emphasized the cyclical nature of life and supported the concept of the Transmigration of Souls, better known today as reincarnation. Once the soul was justified by Osiris after death, it could go on to paradise or return to earth to be reborn in another body. Si-Osire, although certainly Setna's son, is also the reincarnation of the sage Horus-son-of-Paneshe who is allowed to return to earth for a very specific reason: to save Egypt and Egypt's king from the treachery of the Nubian sorcerer. This option seems to have only been open to souls who had been justified by earlier good deeds on earth and, through them, the maintenance of harmony and balance.

Contrasted with the justified soul of Horus-son-of-Paneshe are the dead seen in the underworld. Those who had never succeeded in life and blamed everyone except themselves for failure were sentenced to endless futility as they try to plait ropes which are then eaten by donkeys. People who were never satisfied and always grasping continued to do so eternally as they struggle to get to the food and water they will never reach. This symbolism, as scholar Miriam Lichtheim points out, is distinctly Greek and reminiscent of the story of Tantalus, of Sisyphus, and of the Danaids.

The contrast of the rich and poor man in life and death, later skillfully used by the author of the Book of Luke, illustrates the importance of the central value of ancient Egypt: observance of ma'at. There was nothing wrong, per se, in having riches. Pharaoh, after all, was quite wealthy and yet no one doubted the king would find himself justified in the afterlife and continue on to the Field of Reeds. The autobiographies and tomb inscriptions of plenty of wealthy ancient Egyptians, from different eras, express the same confidence.

What should be noted in this section of the story is what brings the two men to their respective fates: the poor man did "good works" while the rich man's misdeeds were greater than his good ones. This would have been understood as the difference between keeping ma'at as one's focus in life or putting one's self first before the good of others. The rich man would not have been punished for his wealth but for his selfishness and lack of concern for ma'at. In Setna I, the prince learns his lesson about taking what does not belong to him; in the second Setna, one sees in the rich man's fate what happens to those who do not learn that lesson.