In his first work of fiction, the novel The Jericho River ($12.88 on Amazon/ $9.94 on Bookdepository) David Tollen tells a vivid story by beautifully bringing together most major civilizations in history. In this exclusive interview, Jan van der Crabben, CEO of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to author David Tollen, to find out more about his journey writing The Jericho River.

JvdC: The Jericho River is a historical fantasy novel about Western Civilization. Can you tell us a bit more about how you managed to squeeze such a broad area of history into a single novel?

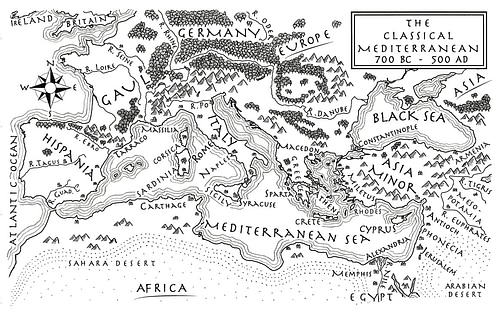

DT: The key is that The Jericho River really is a fantasy, rather than a historical novel. It's set in an alternate world, alongside a river that runs like a timeline. Near the river's headwaters, you have the earliest societies of Western Civilization: Sumer, ancient Egypt, the Minoans etc. And as we move downstream, the adventure takes us through later societies: the ancient Greeks and Romans, Medieval Europe, the Renaissance, and on and on until the modern world. So Jason, the hero, travels through this other world's version of those historic societies. In that way, a quest taking Jason downriver involves one after another of the key societies that shaped Western Civilization.

The story, of course, isn't a history lesson. It's an adventure, with mythic monsters, barbarian pursuers, mysteries, and intrigue. But each step keeps faith with the underlying history. So the monsters and magical creatures come from the myths of each society. And the hero's friends and foes – priestesses, pirates, kings, slaves – come from those societies too; they're based on the sort of people we'd meet there if we could go.

JvdC: You're a lawyer, not a history teacher. What prompted you to write this book?

DT: I've spent half my life reading history for fun, and it was my college major. I also love smart fantasy literature – and to me, the two aren't as separate as you might think. Fantasies are stories of kings and knights, quests and adventure, and mythic creatures. Well, so is a good history. I wanted to share that view with readers who haven't discovered the fun of history, the magic. In particular, I wanted to help young readers retain history – the same way they retain the details of Harry Potter or the geography of Middle Earth or of their favourite video game.

JD: How did you research this book, and how did you decide which parts of history to include and which to leave out? Is there any part of history you wish you had included in retrospect?

DT: The research took forever! I kept thinking I had enough, but then I'd change my mind and return to the books, and to the Internet. And the sources were all over the map, from dense academic treatises to historical atlases – and even children's histories (from reputable publishers). The latter tend to include illustrations and so help capture the look of each society. It was a big job, but fortunately, I had been reading history for years, so I had a good starting point.

One of my choices was whether to tackle the history of all civilization or just of Western Civilization. I chose Western Civilization because I was afraid covering the whole world would lead to a really long story – or to a story that jumped around between barely-connected ancient lands. From there, I chose the individual societies. In some cases, the choice was easy. Lands like Sumer, ancient Egypt, Classical Greece, and Medieval Europe play such central roles that you couldn't explore Western Civilization without them. They're also full of images most people know - mummies, centaurs, castles – so they offered a great playground for fantasy. Not all the choices were so easy, though. I included the Minoans and left out the Hittites, for instance, mostly because the story seemed to flow better that way. I sweated a lot over decisions like that.

In a sense, I regret every society left out, around the world and across time. But I'm not done writing.

JvdC: On your website, you provide a lesson plan for teachers to use your novel in their history class. Apart from using your book, how do you think history education could be improved in general?

DT: I think the key to teaching history well is to tell stories – the more exciting and colourful, the better. I think history classes engage students most if the teacher imagines the whole curriculum as a single, long story, and then adds shorter stories within. Many teachers do a wonderful job with this, but some, particularly at the high school and college levels, lose track of the underlying tale and focus on dry details that don't help tell the core story.

I also think teachers should enhance the narrative with colourful personalities and events. The fact that Eleanor of Aquitaine cheated on the French king with Henry II, and possibly Henry's father too, might not be absolutely central to the evolution of Plantagenet rule in England, but students will certainly retain it. And if they retain “mini-histories” like that, they'll remember the rest of the lesson better.

JvdC: Clearly, history is very important to you. Why do you think it matters, in an age when most people seem to be concerned with STEM subjects?

DT: History is just plain fun.

On top of that, knowledge of history is knowledge of how people behave, particularly important people, as well as groups. There's no way to learn human behaviour better than to see it in action, and that's history. Behavioural knowledge has countless personal benefits, of course, to each of us as a member of any community: office, factory, apartment complex, neighbourhood, social media group, town, etc. But we need that knowledge as voters too, to help us see through conspiracy theories and judge politicians and political movements.

The need for history education seems particularly desperate right now because we live in such unusual times. We're all at sea, in a sense, because of the unprecedented pace of change in technology, world trade, and the environment. We don't know how our world will change next. And while history can't answer that question – it doesn't actually reliably repeat itself – it offers the background knowledge we need to make educated guesses.

JvdC: What's next? Are you working on another novel?

DT: Yes! I recently finished a new book called Secrets of Hominea. It's another novel that uses fantasy to teach and explore – in this case, covering both history and science. This one's for younger readers; it's middle-grade fiction. It's not out yet, but I expect it in 2018. Please stay tuned!

David is a native of Northern California, where he lives with his wife and two sons. He earned a B.A. in history from U.C. Berkeley and law degrees from Harvard Law School and Cambridge University. David also writes about the law, and he's the author of the American Bar Association's bestseller, The Tech Contracts Handbook. For more on David's law-related writing and other work, please visit TechContracts.com.