Howard Carter's 1922 CE discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun was world-wide news but, following fast upon it, the story of the mummy's curse (also known as The Curse of the Pharaoh) became even more popular and continues to be in the present day. Tombs, pharaohs, and mummies attracted significant attention before Carter's find but that was nowhere near the level of interest the public showed afterwards. The world's fascination with ancient Egyptian culture began with the earliest excavations and travelogues published in the 17th and 18th centuries CE but gained considerable momentum in the 19th after Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE), building upon the work of Thomas Young (1773-1829 CE), deciphered ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics through the Rosetta Stone and published his findings in 1824 CE.

Champollion opened the ancient world of Egypt to the modern world because, after his work, scholars could read the texts on the monuments and inscriptions, wrote on their discoveries, and peaked greater interest in the civilization. More and more expeditions were launched to discover ancient artifacts for museums and private collections. Mummies and exotic artifacts were shipped out of Egypt to all parts of the world. Some of these found a home in museums while others were used as coffee tables and conversation curios by the wealthy. This interest in all things Egyptian spilled over into popular culture and it was not long before the young film industry capitalized on it.

The Mummy Films

The first film dealing with the subject was Cleopatra's Tomb in 1899 , produced and directed by George Melies. The film is now lost but, reportedly, told the story of Cleopatra's mummy which, after its accidental discovery, comes to life and terrorizes the living. In 1911 the Thanhouser Company released The Mummy which tells the story of the mummy of an Egyptian princess who is revived through charges of electrical current; the scientist who brings her back to life eventually calms, controls, and marries her.

These early films dealt with Egypt generally and the concept of mummies as a kind of zombie, an animated corpse, but one retaining the person's character and memory. There was no curse involved in these early films but, after 1922, there has hardly been a popular work of film or fiction dealing with Egyptian mummies which does not rely on that plot device to some degree.

The first film on the subject to be a major success was The Mummy (1932) released by Universal Pictures. In the 1932 film, Boris Karloff plays Imhotep, an ancient priest who was buried alive, as well as the resurrected Imhotep who goes by the name of Ardath Bey. Bey is trying to murder Helen Grosvenor (played by Zita Johann) who is the reincarnation of Imhotep's love-interest, Ankesenamun. In the end, Bey's plans to murder and then resurrect Helen as Ankesenamun are thwarted but, before that happens, an audience is made well aware of the curse attached to Egyptian mummies and the serious consequences of disturbing the dead.

This film's great box-office success guaranteed sequels which were produced throughout the 1940's (The Mummy's Hand, The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, and The Mummy's Curse, 1940-1944) spoofed in the 1950's (Abbot and Costello Meet the Mummy, 1955), continued in the 1960's (The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb in `64 and The Mummy's Shroud in `67), and on to the 1971 Blood From the Mummy's Tomb. The mummy horror genre was revived with the remake of The Mummy in 1999 which was a re-make of the 1932 film and just as popular. This film inspired the sequel The Mummy Returns in 2001 and the films on the Scorpion King (2002-2012) which were equally well received for the most part. The film Gods of Egypt (2016) shifted the focus from mummies to Egyptian gods but, according to reports, the latest mummy film to appear in June 2017 returns audiences to the plot of Melies' 1899 film.

The Tomb & the Press

Whether a specific curse is central to the plot of all of these films, the concept of the dark arts of the Egyptians and their ability to transcend death always is. There is no doubt that the Egyptians were interested in the world after death and made ample provision for their continued journey there but they were not interested in cursing or terrorizing future generations. The execration texts which are found inscribed on tombs are simple warnings against grave-robbers and supernatural threats of what will happen to those who disturb the dead; the abundant evidence of tombs looted over the past few thousand years show just how effective these threats were. None of these were able to protect the tomb of its owner as effectively as the one generated and proliferated by the press corps in the 1920's and none will ever be as famous.

Carter became a celebrity overnight when he discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun and, by his own admission, he did not appreciate it much at all. He writes:

Archaeology under the limelight is a new and rather bewildering experience for most of us. In the past we have gone about our business happily enough, intensely interested in it ourselves, but not expecting other folk to be more than tepidly polite about it, and now all of a sudden we find the world takes an interest in us, an interest so intense and so avid for details that special correspondents at large salaries have to be sent to interview us, report our every movement, and hide round corners to surprise a secret out of us. (Carter,63)

Carter had located the tomb in early November 1922 but needed to wait until his sponsor and financial backer, Lord Carnavon, arrived from England to open it. The tomb was opened by Carter, in the presence of Carnavon and his daughter Lady Evelyn on 26 November 1922 and, within a month, the site was attracting visitors from around the world and was already on itineraries for high-priced tours of Egypt.

The press descended on the tomb and its crew within a week and, since the tomb remained a high priority, would not leave. Further complicating the work of the excavation was the insistence of many of these visitors that they should have access to the tomb, guided tours, which caused disruptions in the daily schedule and started to seriously interfere with the scholarly identification and cataloging of the contents.

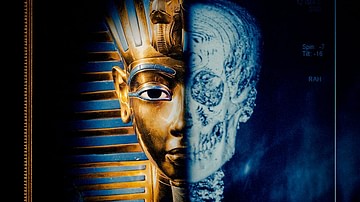

Lord Carnavon was presented with another unexpected surprise. Although Carter believed Tutankhamun's tomb existed intact and could contain great riches, there was no way he could have predicted the incredible cache of treasures it held. When Carter first looked through the hole he made in the door, his only light a candle, Carnavon asked if he could see anything and he famously replied, "Yes, wonderful things" and would later remark that everywhere was the glint of gold (Carter, 35). The magnitude of the find and value of the artifacts precluded the authorities from allowing it to be divided between Egypt and Carnavon; the contents of the tomb belonged to the Egyptian government.

Carnavon, at least publicly, had no problem with this but needed not only a return on his investment but the necessary funds to continue to pay Carter and his team to clear and catalog the tomb's contents. He decided to solve his financial problems and the difficulties caused by the press in a single move: he sold exclusive rights to coverage of the tomb to the London Times for 5,000 English Pounds Sterling up front and 75% of the profits of world-wide sales of their articles to other outlets.

This decision enraged the press corps but was a great relief to Carter and his crew. Carter writes, "we in Egypt were delighted when we heard Lord Carnavon's decision to place the whole matter of publicity in the hands of The Times" (64). There would now be only a small contingent of press at the tomb at any given time instead of an army of them and the team could continue with the excavation without the former interruptions.

The news may have been welcomed by Carter and the others but not so warmly by the press corps. Many remained in Egypt hoping to get a scoop somehow or trying to find some other angle on the event they could exploit for a story; they did not have to wait very long. Lord Carnavon died in Cairo on 5 April 1923 - less than six months after the tomb was opened - and the mummy's curse was born.

The Curse of Tutankhamun

In March of 1923 the best-selling novelist and short story writer Marie Corelli (1855-1924 CE) sent a letter to New York World magazine warning of dire consequences for anyone who disturbed an ancient tomb like Tutankhamun's. She "quoted" from an obscure book she claimed to own to support her claim. Since the publication of her first novel, A Romance of Two Worlds, in 1886 Corelli had been a celebrity and her letter was widely read. Her long-standing dislike for the press and for critics (who panned her books in spite of their popularity) added weight to the letter in that she must have felt her claim important enough to break with her custom of ignoring print publications. No one knows why Corelli sent the letter; she died the next year offering no explanation.

This letter, however, was gold for the media. It was used to support the claim that Carnavon was killed by a curse and Corelli's fame gave it weight in the popular imagination; but she was not the only "authority" on the subject cited by the media. In the United States, the newspaper The Austin American published an article on 9 April 1923 with the headline "Pharaoh Discoverer Killed By Old Curse?" which alludes to the Corelli letter but focuses on the testimony of one Miss Leyla Bakarat who, though having no training in Egyptology or history or curses, confirmed the truth behind Carnavon's death on the basis of her Egyptian heritage: Tutankhamun killed him with a curse through the bite of a spider.

The Australian newspaper, The Argus, reported that Carnavon's death was caused by "the malign influence of the dead pharaoh" and quoted Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (famed as the creator of Sherlock Holmes) and a French spiritualist identified only as M. Lancelin for support. Conan Doyle was himself a spiritualist and a member of the Theosophical Society, as was Marie Corelli, and under other circumstances their religious views would have been handled by the mainstream press with considerably more skepticism. Since only the London Times had access to any news on developments at the tomb, however, other newspaper outlets had to make the most of whatever they had and so the mummy's curse blossomed in articles and editorials in newspapers around the world and those papers sold in record numbers. Egyptologist David P. Silverman describes the situation:

Some of the reporters had the aid of disgruntled Egyptologists, who had not only been denied access to the tomb, but also any information about it. Since there was no love lost between Carter and Carnavon and some of their scholarly colleagues, there was always someone who was willing to provide information about certain objects or inscriptions in the tomb, based solely on published photographs. In this manner, many inscriptions could be construed as curses by the public, especially after a "re-translation" by the press. For example, an innocuous text inscribed on mud plaster before the Anubis shrine in the Treasury stated: "I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber." In the newspaper, it metamorphized into: "...I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever."

Such misrepresentation proliferated, and soon curses were being found in all of the inscriptions. Since few people could read the texts and thereby check the original, the reporters were safe. They could (and did) publish a photograph of the large golden shrine in the Burial Chamber, together with a "translation" of the accompanying inscription: "They who enter this sacred tomb shall swift be visited by wings of death." The carved figure of a winged goddess that accompanied the shrine would no doubt reinforce the "translated" threat. In reality, the texts on this shrine come from The Book of the Dead - a collection of spells intended to ensure eternal life, not shorten it! (Curse, 3)

Papers reported mysterious events surrounding Carnavon's death: the lights went out in Cairo when he died and, his son claimed, Carnavon's dog howled longingly when his master died and then fell over dead. Quite quickly, anyone who died who had any association with the tomb was linked to the curse. George Jay Gould I, who had visited the tomb, died a little over a month after Carnavon. In July of 1923 the Egyptian prince Bey was murdered by his wife in London and his death was also attributed to the curse. Carnavon's half-brother died in September of the same year and, though elderly and in poor health for some time, he was also a victim of the curse.

The Non-Curse & its Legacy

Carnavon actually died of blood poisoning from a mosquito bite which became infected after he sliced it open while shaving. Although his son gave a detailed first-hand report of the howling dog's death, he was nowhere near the dog when it died but away in India. Whether the lights actually went out in Cairo when Carnavon died has never been confirmed but, if they did, it would have been nothing unusual since that was quite a common occurrence in the 1920's.

The other deaths which have since been associated with the curse also have quite logical and natural explanations. The majority of those who participated in the opening and excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb lived for many years after. Egyptologist Arthur Mace, a member of Carter's crew, died in 1928 after a long illness but most went on to lead healthy, successful, and productive lives. Egyptologist Percy E. Newberry, who encouraged Carter to search for the tomb and was active in identifying and cataloging the contents, lived until 1949. Carnavon's daughter, who was present at the tomb's opening, lived until 1980. Carter himself, the man who first opened and entered the tomb and so would be considered the prime candidate to suffer from the curse, lived until 1939.

Carter never mentions the curse in his reports on the work of excavating the tomb but privately considered it nonsense. He did nothing to prevent the press from continuing to develop the story, however, because it had the most wonderful effect of keeping the public away from the tomb. Further, people who had taken artifacts from Egypt in the past for private collections were now sending them back or donating them to institutions because they feared the curse. Silverman notes how "nervous people began cleaning out their basements and attics and sending their Egyptian relics to museums in order to avoid being the next victim" (Curse, 3). Carter would work on the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun for the next decade without the intrusions of the public or the press thanks to the mummy's curse.

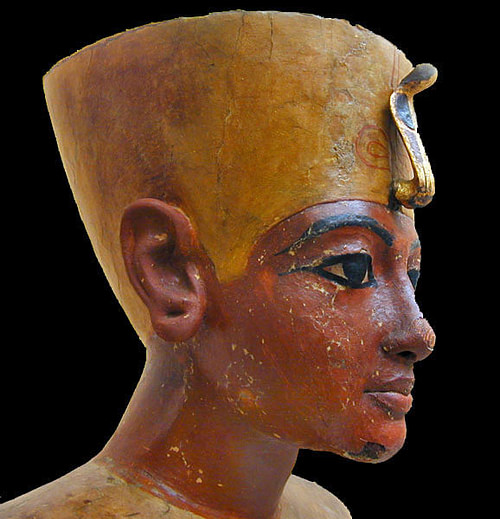

However much good the curse may have done for Carter, and continues to do for the entertainment industry, it has had the unfortunate effect of obscuring the accomplishments of the pharaoh Tutankhamun (1336-c. 1327 BCE) which were quite significant. Tutankhamun's father was the famous "heretic king" Akhenaten (1353-c.1336 BCE) who abolished the traditional religious beliefs and practices of Egypt and instituted his own brand of monotheism. While many in the present day continue to admire Akhenaten as a "religious visionary" his actions were most likely prompted by the growing power, wealth, and prestige of the Cult of Amun and its priests which rivaled that of the king; his vision of a "one true god" effectively nullified the cult and diverted its wealth and property to the crown.

Tutankhamun reinstated the former religion - well over 2,000 years old at the time Akhenaten abolished it - and was working on other initiatives to repair the damage his father had done to Egypt's standing among foreign nations, its military, and its economy, when he died before the age of 20. It was left to the general Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE) to complete Tutankhamun's initiatives and restore Egypt to her former glory.

However intriguing the concept of an ancient Egyptian curse may be, there is no basis for it in reality. The tale of the curse took on a life of its own so that, now, people who know nothing of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb or the origin of the curse associate Egypt with mystical rites, an obsession with death, and curses. Public fascination with the mummy's curse has not lessened in the almost 100 years since it was created by the media and, since such stories and films continue to do well, it will most likely live on for centuries to come; it is hardly the legacy, however, that Tutankhamun would have chosen for himself.