In ancient Egypt, the people sustained the government and the government reciprocated. Egypt had no cash economy until the coming of the Persians in 525 BCE. The people worked the land, the government collected the bounty and then distributed it back to the people according to their need and merit. Although there were many more glamorous jobs than farming, farmers were the backbone of the Egyptian economy and sustained everyone else. These farmers knew how to enjoy themselves, greeting the day as another opportunity to make the earth yield food, but looked forward to relaxation time at festivals because they worked so hard, so long, every day; but, in ancient Egypt, so did everyone else.

Egypt operated on a barter system up until the Persian invasion of 525 BCE and the economy was based on agriculture. The monetary unit of ancient Egypt was the deben which, according to historian James C. Thompson, "functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin" (Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was "approximately 90 grams of copper; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value" (ibid). Thompson continues:

Since seventy-five litters of wheat cost one deben and a pair of sandals also cost one deben, it made perfect sense to the Egyptians that a pair of sandals could be purchased with a bag of wheat as easily as with a chunk of copper. Even if the sandal maker had more than enough wheat, she would happily accept it in payment because it could easily be exchanged for something else. The most common items used to make purchases were wheat, barley, and cooking or lamp oil, but in theory almost anything would do. (1)

Laborers were often paid in bread and beer, the staples of the Egyptian diet. If they wanted something else, they needed to be able to offer a skill or some product of value, as Thompson points out. Fortunately for the people, there were many needs which had to be met.

The Satire of the Trades

The commonplace items taken for granted today - a brush, a bowl, a cup - had to be made by hand. In order to have paper to write on, papyrus plants had to be harvested, processed, and distributed, laundry had to be washed by hand, clothing sewn, sandals made, and each of these jobs had their own rewards but also difficulties. Simply doing laundry could mean risking one's life. Laundry was washed by the banks of the Nile River which was home to crocodiles, snakes, and the occasional hippopotamus. The reed cutter, who harvested papyrus plants along the Nile, also had to face these same hazards daily.

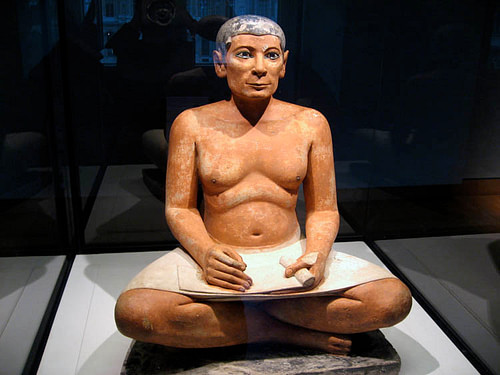

These jobs were all held by those at the bottom of the Egyptian social hierarchy and are described in withering detail in a famous literary work from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) known as The Satire of the Trades. This piece (also known as The Instructions of Dua-Khety) is a monologue in which a father, bringing his son to school, describes for the boy all of the difficult and nasty jobs which people have to do every day and compares these to the comfortable and rewarding life of the scribe. Although the piece is obviously satirical in its exaggerated depictions, the description of jobs and their difficulty is accurate.

The father characterizes the life of the carpenter as "miserable" and how the field hand on farms "cries out forever" while the weaver is "wretched" (Simpson, 434). The arrow maker wears himself out trying to gather raw materials and the merchant has to leave home with no guarantee of returning and finding his family intact. The washerman "launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile" and his children want nothing to do with him because he is always covered in other people's filth. The fisherman is "more miserable than any other profession" because he must count on his good catch in a day to make a living and must also contend with the dangers in the water which often catch him unawares as "no one told him that a crocodile was standing there" and he is swiftly taken (Simpson, 435). All of these jobs are described in great detail in order to impress on the boy that he should embrace the life of the scribe, the greatest job one could have, as he tells his son:

It is to writings that you must set your mind. See for yourself, it saves one from work. Behold, there is nothing that surpasses writings!...I do not see an office to be compared with it, to which this maxim could relate: I shall make you love books more than your mother and I shall place their excellence before you. It is indeed greater than any office. There is nothing like it on earth. (Simpson, 432-433)

The writer of the Satire, obviously a scribe himself, may have exaggerated somewhat for effect but his argument is basically sound: the occupation of scribe was among the most comfortable in ancient Egypt and certainly compared favorably with most jobs.

Upper-Class Jobs

The jobs of the upper class are fairly well known. The king ruled by delegating responsibility to his vizier who then chose the people beneath him best suited to the job. Bureaucrats, architects, engineers, and artists carried out domestic building projects and the implementation of policies, and the military leaders took care of defense. The priests served the gods, not the people, and cared for the temple and the gods' statues while doctors, dentists, astrologers, and exorcists dealt directly with clients and their needs through their particular (and usually high-priced) skills in magic.

In order to be a member of most of these professions, one had to be literate and so first had to become a scribe. This job required many years of training, apprenticeship, and hard work in memorizing hieroglyphic symbols and practicing calligraphy, but this kind of work would hardly have been thought difficult by many of the lower classes.

As with most if not all civilizations from the beginning of recorded history, the lower classes provided the means for those above them to live comfortable lives, but in Egypt, the nobility took care of those under them by providing jobs and distributing food. One needed to work if one wanted to eat, but there was no shortage of jobs at any time in Egypt's history, and all labor was considered noble and worthy of respect.

Lower-Class Jobs

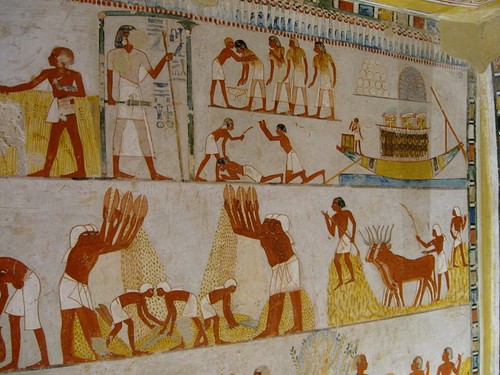

The details of these jobs are known from medical reports on the treatment of injuries, letters, and documents written on various professions, literary works (such as The Satire on the Trades), tomb inscriptions, and artistic representations. This evidence presents a comprehensive view of daily work in ancient Egypt, how the jobs were done, and sometimes how people felt about the work.

In general, the Egyptians seem to have felt pride in their work no matter their occupation. Everyone had something to contribute to the community, and no skills seem to have been considered non-essential. The potter who produced cups and bowls was as important to the community as the scribe, and the amulet-maker as vital as the pharmacist and, sometimes, as the doctor.

Part of making a living, regardless of one's special skills, was taking part in the king's monumental building projects. Although it is commonly believed that the great monuments and temples of Egypt were achieved through slave labor - specifically that of Hebrew slaves - there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. The pyramids and other monuments were built by Egyptian laborers who either donated their time as community service or were paid for their labor.

It is also a misconception that slaves in Egypt were routinely beaten and only worked as unskilled laborers. Slaves in ancient Egypt came from many different ethnicities and served their masters in many different capacities according to their skills. Unskilled slaves were used in the mines, as domestic help, and in other menial capacities but were not employed in actually building tombs and monuments like the pyramids.

The Pyramid Builders

Egyptians from every occupation could be called on to labor on the king's building projects. Stone had to first be quarried from the mines and this required slaves to split the blocks from the rock cliffs. This was done by inserting wooden wedges in the rock which would swell and cause the stone to break from the face. The often huge blocks were then pushed onto sleds and rolled to a different location where they could be cut and shaped.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is comprised of 2,300,000 blocks of stone and each of these had to be quarried and shaped. This job was done by skilled stonemasons working with copper chisels and wooden mallets. As the chisels would blunt, a specialist in sharpening would take the tool, sharpen it, and bring it back. This would have been constant daily work as the masons could wear down their tools on a single block.

The blocks were then moved into position by unskilled laborers. These people were mostly farmers who could do nothing with their land during the months when the Nile River overflowed its banks. Egyptologists Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs explain:

For two months annually, workmen gathered by the tens of thousands from all over the country to transport the blocks a permanent crew had quarried during the rest of the year. Overseers organized the men into teams to transport the stones on sleds, devices better suited than wheeled vehicles to moving weighty objects over shifting sand. (17)

Once the pyramid was complete, the inner chambers needed to be decorated by artists. These were scribes who painted the elaborate images known as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and scenes from The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Interior work on tombs and temples also required sculptors who could expertly cut away the stone around certain figures or scenes to leave them in relief. While these artists were highly skilled, everyone - no matter their job the rest of the year - was expected to contribute to communal projects. This practice was in keeping with the value of ma'at (harmony and balance) which was central to Egyptian culture. One was expected to care for others as much as one's self and contributing to the common good was an expression of this.

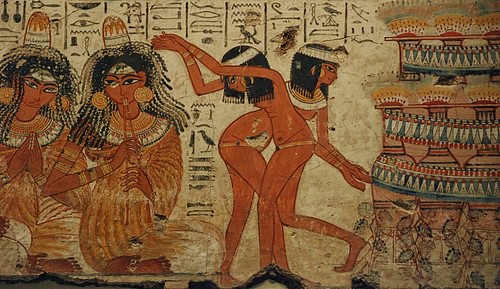

The jobs people held throughout the year were as varied as occupations are today. When one was not being called upon by community or king to participate in a project, one worked jobs as varied as beer brewer, jewelry maker, sandal maker, basket weaver, armorer, blacksmith, baker, reed cutter, landscaper, wig maker, barber, manicurist, coffin maker, canal digger, painter, carpenter, merchant, chef, entertainer, servant, and many other occupations. The upper class relied heavily upon their servants, and one could make a good living and find advancement in domestic service.

Servants

A servant in a noble or upper-class home might be a slave but usually was a young man or woman of good character who worked diligently. Girls served female mistresses, and boys served male masters. A young person would enter service around the age of 13 and could rise to a prominent position in the household. Personal letters, as well as Letters to the Dead, make clear that a good servant was highly valued and considered vital to the maintenance of the home.

A male servant would serve as his master's messenger and personal butler but could also rise to the position of overseeing other servants in the house and holding considerable authority. Servants could sometimes find themselves working for unpleasant and demanding masters, but they were usually treated well. There is an often-repeated story of Pepi II (2278-2284 BCE) and his aversion to flies: he would smear servants with honey and set them at distances around him to attract the insects. This story is inaccurate, however, as Pepi II actually used slaves as his human insect repellents, not servants. The purposeful mistreatment of a servant would have been considered unacceptable behavior.

Female servants were directly under the supervision of the woman of the house unless she could afford to hire a household manager. This position was usually given to a woman who had proven her worth through years of devoted service. A household manager could live as comfortably as a scribe and enjoyed job security as a valuable member of the home.

The female servants of the wealthy or influential had easier lives than those who served the queen or nobility because the latter had more responsibilities. A servant to the queen had to take particular care of her mistress' wardrobe and wigs, for example, because these would receive more attention than other women's. In the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) the job of a servant of the queen was even more difficult because, when one's mistress died, one went to join her.

Queen Merneith's servants were all sacrificed after her death and buried with her so they could continue their service in the afterlife. This same practice was observed with other rulers, male and female. Future servants were spared this fate with the advent of the shabti doll in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE). The shabti (also known as ushabti) served as a replacement for a worker in the afterlife, and so the dolls were buried with the deceased instead of sacrificed servants.

Military Service, Entertainers, & Farmers

Women entered domestic service more often than men, who frequently chose to join the army from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) onwards. Although one could make a living as a soldier, it was difficult and dangerous work. A significant disadvantage was not only dying on the job but the possibility of being killed somewhere beyond Egypt's borders. Since Egyptians believed that their gods were tied to the land, they feared dying in another country because they would have a harder time making their way to the afterlife. Still, this did not dissuade men from enlisting and, in the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) Egypt had one of the most skilled professional armies in the world.

The armed forces also employed many who were not enlisted to fight. Arms manufacture was always steady work, and after the Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot to Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE), tanners and curriers were required to make tack and skilled workers to build chariots.

Men and women could also become entertainers, primarily musicians and dancers. Female dancers were always in high demand as were singers and musicians who would often work for temples providing music at ceremonies, rituals, and festivals. Women were often singers, musicians, and dancers and could command a high price for performances, especially dancers. The dancer Isadora of Artemisia (c. 200 CE) received 36 drachmas a day for performances in Egypt during the Roman Period and for one six-day show was paid 216 drachmas (approximately $5,400). Entertainers performed for the laborers during their building projects, on street corners, in bars, in the market, and, as noted, in temples. Music and dance were highly regarded in ancient Egypt and were considered essential to daily life.

At the bottom rung of all these jobs were the people who served as the basis for the entire economy: the farmers. Farmers usually did not own the land they worked. They were given food, implements, and living quarters in return for their labor. The farmer rose before sunrise, worked the fields all day, and returned home toward sunset. Farmers' wives would often keep small gardens to supplement family meals or to trade for other goods.

Many women chose to work out of their homes, making beer, bread, baskets, sandals, jewelry, amulets, or other items for barter. They took on this work in addition to their daily chores which also began before sunrise and continued past nightfall. The Egyptian government was aware of how hard the people worked and so staged a number of festivals throughout the year to show appreciation and give them days off to relax.

As the gods had created the world and everything in it, no job was considered small or insignificant, despite the view of the author of The Satire of the Trades. There is no doubt there were many people who did not love their job every day, but each job was considered an important contribution to the harmony and balance of the land.