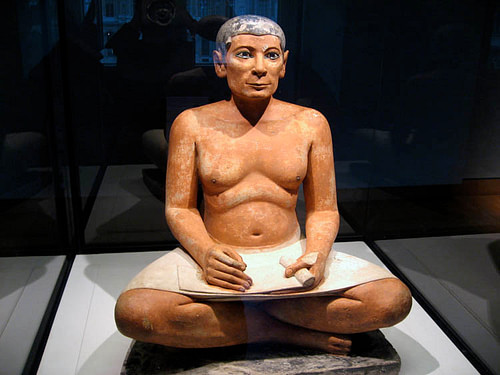

The literature of ancient Egypt is as rich and varied as any other culture. From the inscriptions of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) through the Love Poems of the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) the Egyptian scribes produced an impressive body of work.

Egyptian literature would influence some of the greatest works of other cultures, most notably the books by Hebrew scribes which would finally be included in the Bible. Literary forms of the short story, novel, ballad, prose-poem, hymn, incantation, biography, and autobiography were all explored through genres such as the ghost story, adventure story, love story, and didactic compositions intended to teach a clear and obvious message.

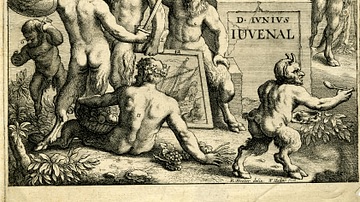

These didactic tales, also known as Wisdom Literature, reached their height of expression during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), which is generally considered the pinnacle of Egyptian art and culture. They sometimes take the form of a father (a king) addressing his son as in The Instructions of King Amenhemat I for his son Senruset I. In other works, the plot unfolds from a narrator speaking in the first person to an audience (The Admonitions of Ipuwer) or a carefully constructed tale told in third-person narration (The Eloquent Peasant). These are all quite serious literary works famous for their articulate presentation of the values of Egyptian culture, but there is another among them which combines solemn advice with comical exaggeration to make its point and is, in fact, the first example of literary satire: The Instruction of Dua-Khety - also known as The Satire of the Trades.

Narrative Form & Summary

The Satire of the Trades takes its cue from grand and solemn works such as The Instructions of King Amenhemat I or the earlier works from the Old Kingdom such as The Instruction of Ptahhotep: a father is giving helpful advice to his son. In the case of Dua-Khety, however, the greater part of the manuscript is devoted to impressing upon the boy the rich life which awaits him as a scribe by presenting every other job as unending misery.

The story begins as Dua-Khety is sailing down the Nile with his son, Pepi, on their way to enrol the boy in school. There is no indication in the text that Pepi has complained about becoming a scribe or expressed the desire to do anything else. Since it is obvious that Dua-Khety is a scribe, it would be natural for his son to follow in this occupation. Dua-Khety, however, begins his instruction as though Pepi has objected to it.

For the first 22 chapters of the text, the father details all the horrors his son could expect in any other job while impressing upon him the glorious life of the scribe. He concludes by saying, "But if you understand writings, then it will be better for you than the professions which I have set before you" (Simpson, 435). He then goes on, in the last eight chapters, to give general advice in keeping with the tone and solemnity of earlier Wisdom Literature.

Satire or Serious Work

These last eight chapters, obviously meant to be taken seriously, influenced early interpretations claiming the piece was to be taken completely seriously throughout in keeping with older Instruction works. Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim addresses how even the great scholar Wolfgang Helck "has denied its satiric character and has claimed it to be a wholly serious, non-humorous work" (184). Helck's assertion seems an almost incredible claim in light of the fact that the piece is obviously intended to amuse. The descriptions of the trades are so uniformly horrific that, if they were actual representations of these jobs, no one would have wanted to do them. There is no doubt much truth to many aspects of these descriptions but that is precisely how satire works. Lichtheim writes:

What are the stylistic means of satire? Exaggeration and a lightness of tone designed to induce laughter and a mild contempt. Our text achieves its satirical effects by exaggerating the true hardships of the professions described and by suppressing all their positive and rewarding aspects. If it were argued that the exaggerations were meant to be taken seriously, we would have to conclude that the scribal profession practiced deliberate deception out of a contempt for manual labor so profound as to be unrelieved by humor. Such a conclusion, however, is belied by all the literary and pictorial evidence. For tomb reliefs and texts alike breathe joy and pride in the accomplishments of labor. (184)

It is generally accepted today that the work is satire and is meant to amuse but the latter part (Chapters 23-30) returns to the paradigm of non-satirical Wisdom Literature. This section of the text, as well as other Egyptian works such as The Instruction of Amenemope (c. 1570-c. 1069 BCE), would influence the authors of the biblical Book of Proverbs. Egyptologist Jaroslav Cerny (1898-1970 CE) substantiated that The Instruction of Amenemope and so, obviously, The Satire of the Trades, pre-dates the Book of Proverbs as well as the other books included in the Bible.

The Text

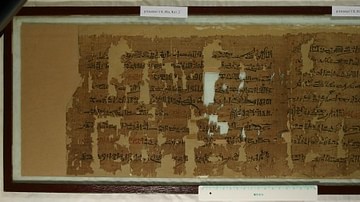

The manuscript of The Satire of the Trades exists only in copies from the 18th and 19th dynasties of the New Kingdom known as P. Sallier II and P. Anastasi VII both now housed in the British Museum. The manuscripts are complete but damaged enough to allow for a number of different interpretations and translations of certain lines. The overall text, however, is recognizable in all of these translations.

The following translation comes from William Kelly Simpson following that of Wolfgang Helck from his 1970 CE work:

1. The beginning of the teaching which the man of Tjel named Dua-Khety made for his son named Pepy, while he sailed southwards to the Residence to place him in the school of writings among the children of the magistrates, the most eminent men of the Residence.

2. Thereupon he spoke to him: Since I have seen those who have been beaten, it is to writings that you must set your mind. See for yourself, it saves one from work. Behold, there is nothing that surpasses writings! They are like a boat upon the water. Read then at the end of the Book of Kemyet and you will find this statement in it saying: As for a scribe in any office in the Residence, he will not suffer want in it.

3. When he fulfils the bidding of another, he does not come forth satisfied. I do not see an office to be compared with it, to which this maxim could relate: I shall make you love books more than your mother and I shall place their excellence before you. It is indeed greater than any office. There is nothing like it on earth. When he began to become sturdy but was still a child, he was greeted respectfully. When he was sent to carry out a task, before he returned he was dressed in adult garments.

4. I do not see a stoneworker on an important errand or a goldsmity in a place to which he has been sent, but I have seen a coppersmith at his work at the mouth of his furnace. His fingers were like the claws of the crocodile and he stank more than fish eggs.

5. Every carpenter who bears the adze is wearier than a laborer. His field is his wood, his hoe is the axe. It is the night that will rescue him, for he must labor excessively in his activity. But at nighttime he still must light his lamp.

6. The jeweler pierces stone in stringing beads in all kinds of hard stone. When he has completed the inlaying of the eye amulets, his strength vanishes and he is tired out. He sits until the arrival of the sun, his knees and his back bent at the place called Aku-Re.

7. The barber shaves until the end of the evening. But hs must be up early, crying out, his bowl upon his arm. He takes himself from street to street to seek out someone to shave. He wears out his arms to fill his belly, like bees who eat only according to their work.

8. The arrowmaker goes north to the Delta to fetch himself arrows. He must work excessively in his activity. When the gnats sting him and the sand fleas bite him as well, then he is judged.

9. The potter is covered with earth, although his lifetime is still among the living. He burrows in the field more than swine to bake his cooking vessels. His clothes being stiff with mud, his headcloth consists only of rags so that the air which comes forth from his burning furnace enters his nose. He operates a pestle with his feet, with which he himself is pounded, penetrating the courtyard of every house and driving earth into every open place.

10. I shall also describe to you the like of the mason-bricklayer. His kidneys are painful [his work pains him]. When he must be outside in the wind, he lays bricks without a loin cloth. His belt is a cord for his back, a string for his buttocks. His strength has vanished through fatigue and stiffness, kneading all his excrement. He eats bread with his fingers, although he washes himself but once a day.

11. It is miserable for the carpenter when he planes the roofbeam. It is the roof of a chamber 10 by 6 cubits. A month goes by in laying the beams and spreading the matting. All the work is accomplished. But as for the food which should be given to his household while he is away, there is no one who provides for his children.

12. The vintner hauls his shoulder-yoke. Each of his shoulders is burdened with age. A swelling is on his neck, and it festers. He spends the morning in watering leeks and the evening with corianders, after he has spent the midday in the palm grove. So it happens that he sinks down at last and dies through his deliveries more than one of any other profession.

13. The field hand cries out forever. His voice is louder than the raven's. His fingers have become ulcerous with an excess of stench. He is tired out in Delta labor, he is in tatters. He is well among lions but his experience is painful. The forced labor then is tripled. If he comes back from the marshes there, he reaches his house worn out, for the forced labor has ruined him.

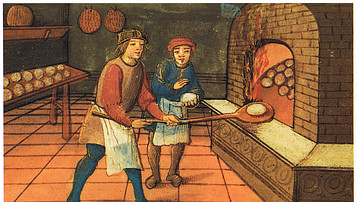

14. The weaver inside the weaving house is more wretched than a woman. His knees are drawn up against his belly. He cannot breathe the air. If he wastes a single day without weaving, he is beaten with fifty whip lashes. He has to give food to the doorkeeper to allow him to come out to the daylight.

15. The weapon maker, completely worn out, goes into the desert. Greater than his own pay is what he has to spend for his she-ass for its work afterwards. Great is also what he has to give to the fieldhand to set him on the right road to the flint source. When he reaches his house in the evening, the journey has ruined him.

16. The courier goes abroad after handing over his property to his children, being fearful of the lions and the Asiatics. He only knows himself again when he is back in Egypt. He reaches his household by evening, but the journey has ruined him. But his house by then is only a garment and a paved road. There is no happy homecoming.

17. The furnace-tender, his fingers are foul, the smell thereof is as corpses. His eyes are inflamed because of the heaviness of the smoke. He cannot get rid of his dirt, although he spends the day cutting reeds. Clothes are an abomination to him.

18. The sandalmaker is utterly wretched carrying his tubs forever. His stores are provided with carcasses and what he bites is hides.

19. The washerman launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile. `I shall go away, father, from the flowing water,' said his son and daughter, `to a more satisfactory profession, one more distinguised than any other profession.' His food is mixed with filth, and there is no part of him which is clean. He cleans the clothes of a woman in menstruation. He weeps when he spends all day with a beating stick and a stone there. One says to him, "Dirty laundry, come to me", the brim overflows.

20. The fowler is utterly afflicted while searching out for the denizens of the sky. If the flock passes by above him, then he says, `Would that I might have nets'. But God will not let this come to pass for him for He is opposed to his activity.

21. I mention to you also the fisherman. He is more miserable than one of any other profession, one who is at his work in the river infested with crocodiles. When the totaling of his account is subtracted for him, then he will lament. One did not tell him that a crocodile was standing there and fear has now blinded him. When he comes to the flowing water, so he falls as through the might of God. See, there is no office free from supervisors except the scribe's. He is the supervisor!

22. But if you understand writings, then it will be better for you than the professions which I have set before you. Behold the official and the dependent pertaining to him. The tenant farmer of a man cannot say to him, `Do not keep watching me.' What I have done in journeying southward to the Residence is what I have done through love of you. A day at school is advantageous to you. Its work of mountains is forever, while the workmen I have caused you to know hurry and I cause the recalcitrant to hasten.

23. I will also tell you another matter to teach you what you should know at the station of your debating. Do not come close to where there is a dispute. If a man reproves you, and you do not know how to oppose his anger, make your reply cautiously in the presence of listeners.

24. If you walk to the rear of officials, approach from a distance behind the last. If you enter while the master of the house is at home, and his hands are extended to another in front of you, sit with your hand to your mouth. Do not ask for anything in his presence. But do as he says to you. Beware of approaching the table.

25. Be serious, and great as to your worth. Do not speak secret matters. For he who hides his innermost thoughts is one who makes a shield for himself. Do not utter thoughtless words when you sit down with an angry man.

26. When you come forth from school after midday recess has been announced to you, go into the courtyard and discuss the last part of your lesson book.

27. When an official sends you on a mission, then say what he said. Neither take away nor add to it. The impatient man falls into oblivion, his name will not endure. He who is wise in all his ways, nothing will be hidden from him, and he will not be rebuffed from any station of his.

28. Do not say anything false about your mother. This is an abomination to the officials. The offsprting who does useful things, his condition is equal to the one of yesterday. Do not indulge with an undisciplined man, for it is bad after it is heard about you. When you have eaten three loaves of bread and swallowed two jugs of beer, and the body has not yet had enough, fight against it. But if another is satiated, do not stand around, take care not to approach the table.

29. See, it is good if you write frequently. Obey the words of the officials. Then you may assume the characteristics of the children of men and you may walk in their footsteps. One values a scribe for his understanding, for understanding transforms an eager person. Beware of words against it. Your feet shall not hurry when you walk. Do not approach only a trusted man, but associate with one more distinguised than you. But let your friend be a man of your generation.

30. See, I have placed you on the path of God. The fate of a man is on his shoulders on the day he is born. He comes to the judgment hall and the court of magistrates made for the people. See, there is no scribe lacking sustenance, the provisions of the royal house l.p.h. [Life, Prosperity, Health]. It is Meskhenet [goddess of childbirth who provides the soul] who is turned toward the scribe who presents himself before the court of magistrates. Honor your father and mother who have placed you on the path of the living. Mark this, which I have placed before your eyes, and the children of your children.

It has come to an end in peace.

Commentary

The narrator begins by identifying himself as a man of Tjel which, according to Simpson, is the city of "Sile in the northeast Delta on the borders of Egypt" (432). This could mean, as Simpson suggests, that "the man and his son are characterized as citizens of an outlying district far from the cultural and political center of Memphis" and are thus unsophisticated (432). It could also mean, however, that the man and his son, distanced from polite urban society, are more used to honest, blunt speech and this would go toward highlighting the humorous aspects of the piece: one is hearing from a narrator who sees nothing wrong in what he is saying because he knows he is only speaking the truth.

In Chapter 3 the narrator sets the tone and message firmly by asserting that a scribe, though still a child, deserves respect and only garners greater admiration as he becomes older. Chapter 3 then launches into the narration of the different trades in which each is as bad or worse than the last mentioned until the narrator has reached the end.

This section of the piece would have been understood in the same light as a modern-day 'roast' at which the guest of honor is repeatedly insulted by friends and colleagues. The comical nature of the descriptions is epitomized by Chapter 20 in which the fowler who has gone out to catch birds has no nets because God hates him or in Chapter 16 when the courier (merchant) returns home to find nothing but a shirt and the driveway because he has been away so long.

Beginning with Chapter 23 the narrator shifts to his serious advice on how his son should comport himself. He tells Pepi not to become involved with angry people, to remain humble when in the presence of his superiors, to refrain from telling secrets, and to honor his mother and father, among other pieces of advice.

These maxims would later be translated, as much of Egyptian literature was, by the Hebrew scribes who wrote the books of the biblical Old Testament as well as the Greek writers who produced the New Testament. Proverbs 22:24 corresponds to Chapter 23; Proverbs 25:7 and Luke 14: 7-10 to Chapter 24; Proverbs 21:23 and James 3:1 to Chapter 25, and so on.

The brilliance of the piece is its use of the old Instruction form of Wisdom Literature to surprise and delight an audience while still providing, toward the end, what that audience would have expected from such a work. Any humor operates from the principle of surprise and The Satire of the Trades relies on this. When Dua-Khety first begins to speak, the audience would have expected a serious representation of the professions; not an exaggerated condemnation of them. There would have been many people who held these jobs in the audience where the satire would have been read, and those who could laugh at themselves must have laughed hard.