After securing the eastern Mediterranean seaboard and Egypt, Alexander the Great pushed east into Mesopotamia with the intention of bringing Darius to battle. After crossing the Euphrates River unopposed, he marched his army eastward along the foothills of the Armenian mountains before crossing the Tigris River. Once across the Tigris, Macedonian mounted scouts reported seeing Persian cavalry in the distance. Taking no chances, Alexander drew his army up in battle order, and, whilst the bulk of his troops cautiously advanced, he personally led a contingent of horsemen and light infantry against these Persians, scattering them and taking prisoners. He deduced from his captives that Darius was awaiting him at Gaugamela, a small village beside the river Bumodus.

Alexander sets up Camp

Alexander halted his army and built a fortified encampment. The gap between the two armies was now about seven miles, although neither side was visible to the other because a low range of hills ran between them. Leaving his baggage, camp followers, and prisoners under guard, Alexander left his encampment after nightfall, with his troops prepared for battle.

At about midnight, the Macedonian army crested the hills, taking in the thousands of twinkling Persian campfires below. Whilst the men halted and rested, Alexander took some of his Companions and light infantry down to reconnoitre the plain. His generals urged him to make a night attack, but Alexander refused - a good thing, because the Persians were expecting such a move and their entire army was under arms, the men already in their battle formations.

Alexander had learnt much from his captured Persians. The plain that Darius had chosen to fight his battle upon had been further levelled, to enable his horsemen and chariots to manouevre effectively, and traps had been lain. Alexander knew of these traps, and, although unclear when, they were rendered harmless.

Battle Lines

The battle itself began about mid-morning. The scene that confronted Alexander's army must have been awe-inspiring. The Persian line stretched across the plain, far outflanking the Macedonians. The Persian left flank was composed of cavalry - Bactrians, Scythians, and Arachotians, some of the finest mounted warriors in the Empire. Screening this force was more cavalry and 100 scythed chariots. In the centre, where Darius himself was stationed, was a vast horde of Persian infantry, and Darius' 2,000 - 10,000 mercenary Greeks. These men were the finest foot-soldiers in the Achaemenid host, and Darius was relying on them to halt the advance of the dreaded Macedonian phalanx. A further 50 scythed chariots and 15 elephants screened the centre.

The Persian right was held mostly by cavalry - Syrians, Mesopotamians, and warriors from the Persian Gulf. Although the figure of a million infantry and 40,000 cavalry ( including 200 scythed chariots and 15 elephants) is almost certainly exaggerated, Alexander's army, with 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry, was nevertheless heavily outnumbered. Modern estimates put the size of Darius force at anywhere between 90,000 to 250,000 men.

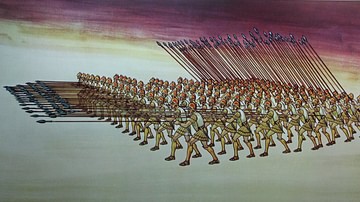

Yet, despite the numbers arrayed against them, the Macedonians enjoyed some advantages. The infantry, the pezhetairoi or phalangites, fought in a densely packed phalanx formation. Their chief weapon, the sarissa, was a pike of up to twelve cubits (18 ft) in length. In terms of length alone it conferred an enormous advantage to the Macedonian infantry, because they could start the slaughter whilst the enemy were still attempting to bring their own weapons to bear. In addition, footsoldiers were equipped with a sword, either a traditional Greek xiphos or the curved kopis.Those phalangites who fought in the front ranks of the phalanx were well armoured with cuirasses, helmets, and greaves, and all soldiers carried a two-foot wide circular shield.

Persian infantry, by contrast, wore little to no armour, and most carried wicker shields that offered no defence against the brutal power of sarissae. Most were levies with little military training, and although the Persian host was vast, it lacked much in the manner of cohesion and discipline. Foremost in their minds would also most likely have been the knowledge that they were facing a general who had bested their king at the battle of Issus, and the fact that Darius had fled at Issus. This knowledge would also have influenced Alexander's men.

The chief advantages enjoyed by the Persians were their cavalry and the prepared battlefield. Conversely, the smooth plain was also ideal for the deployment of the Macedonian phalanx - the slightest dip or obstruction could ruin the cohesion of an advancing phalanx, and the bristling hedge of glittering pikes would dissuade any horse.

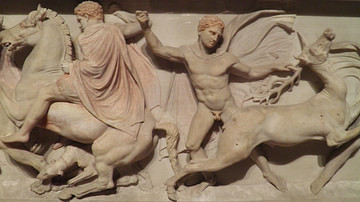

Alexander stationed himself on the Macedonian right, with the bulk of his Companion and mercenary cavalry, and large numbers of psiloi (light infantry). Companion cavalry carried the xyston - a long, double-headed lance that was wielded two-handed. If the shaft snapped, as it often did, the warrior could reverse it and thrust with the other end. Companions wore breastplates and helmets and wielded a kopis (chopper) in the brutal scrummage of close-in combat.

The Macedonian infantry held the centre, with the entire line arrayed in echelon, slanting away diagonally backward to the left flank. On the left, General Parmenio commanded more infantry and the Thessalian cavalry (sometimes said to be the best cavalry in Alexander's army), and to him fell a tough task: to contain the main Persian attack whilst Alexander and his Companions dealt the death blow to Darius' army.

Aware that the phalanx would be vulnerable whilst he and his cavalry were engaged, Alexander stationed another phalanx behind the main battle line, comprised mostly of Greek mercenaries. This rear phalanx would face about in the event of an encirclement, a highly likely event given Darius' vast numbers.

Opening Moves

Initially, Alexander led his cavalry out to the right. Darius ordered his left-wing Bactrian and Scythian cavalry, under the command of his cousin Bessus, to keep pace with Alexander's outflanking movement. Furthermore, as the Macedonian line advanced, they were subjected to 'phalanx drift' - a phenomenon that occured as each man huddled instinctively behind his right-hand partners shield, resulting in a gradual crabbing drift to the right. Aware that the Macedonian line might thus move out of his prepared ground, Darius ordered his left flank to envelop Alexander's mercenary cavalry.

Alexander then launched a determined assault on the centre of the enveloping Persian left wing, which was counterattacked by Scythian and Bactrian horsemen. Although the initial envelopment was thrown back, fresh reserves of Bactrian cavalry rallied the fleeing left wing and a savage cavalry battle erupted in which many on both sides lost their lives. Alexander's cavalry were fighting against some of the finest horsemen in the ancient world - many Scythians, or Saka, were particularly well armoured in the cataphract fashion. But Alexander persisted in his assault, and the Persian left finally began to waver.

.

Witnessing the failure of his cavalry to contain Alexander's outflanking manouevre, Darius committed his chariots and elephants. They ran into a thick screen of Macedonian light infantry, who grabbed the chariot reins and killed horses and drivers. Other chariots and elephants made it through the psiloi and attempted to attack the phalanx - the phalangites opened their ranks, allowing the chariots to drive through and be dealt with by Hypaspists and horse-grooms at the rear. The pezhetairoi also hammered the shafts of their sarrissae against their shields, causing a frightful din which panicked the chariot horse teams. The chariot assault had been a failure, although how much of a failure is open to debate: Diodorus states that they managed to inflict gruesome casualties before being neutralised.

Mid-Battle Maneuvres

Darius now committed reserve Persian cavalry to contain Alexander's right, thus opening up a gap in his centre. Leaving behind his commander Aretas and some cavalry to deal with the Persian horsemen that still attempted to envelop the Macedonian right flank, Alexander wheeled his squadrons left, a complete about-turn that highlights the Macedonian's discipline and training. The manouevre would have been further complicated by the thick pall of choking dust and general mayhem that now blanketed the battlefield.

Forming his cavalry into a gigantic wedge, with himself and the Companions at the tip, Alexander met with the right-wing infantry elements of his centre and led a ferocious charge into the gap in the Persian lines, making for Darius himself. The phalanx, along with Thracian mercenaries and light infantry, followed, and the sheer momentum of their assault carried them deep into the Persian lines. Darius decided not to hang around: He fled, and the fight went out of those Persians who witnessed his flight. Thousands of Persian infantry began to rout from the field. On the left, Bessus finally gave way before the cavalry of Admetus.

Meanwhile, on the Macedonian left, Parmenion was in trouble. The right-wing elements of the line had followed Alexander into the Persian centre, but their comrades had been forced to go to the assistance of the left flank. This created a gap in the Macedonian battle line, and Persian and Indian cavalry swarmed through this gap. Some swung around to attack the Macedonian left from the rear, but most bypassed the rear phalanx and made for the Macedonian camp, several miles away. This was a serious tactical error: Had they all swung about to attack the Macedonian left, they may well have succeeded in destroying a large part of Alexander's army.

As it was, the Macedonian camp guards were slaughtered and the prisoners freed, and these now joined the battle. The Macedonian rear phalanx ran back to save the camp, an impressive feat given that battle had already been raging for perhaps several hours and they made the run in full armour and carrying their weapons.

Mazaeus, the commander of the Persian left, pressed his advantage. He was unaware that Darius had fled the field and it is likely that the Persian right believed they were winning the battle. Parmenion was virtually surrounded and despatched a messenger to find Alexander and request assistance. Miraculously, this messenger succeeded in his task, and Alexander abandoned his pursuit of the fleeing Persian centre and galloped back to help Parmenion. On the way, he and his Companions ran head-on into thousands of withdrawing Persian and Indian cavalry - many of whom were returning after plundering his baggage - and the Companions were forced to hack a path through them to reach the Macedonian left.

With Alexander's arrival, Mazaeus realised that the Persian army was routing and began to withdraw, pursued relentlessly by Parmenion's Thessalian horse. Alexander resumed his pursuit of Darius with 500 cavalry, chasing and slaughtering fleeing Persians until dusk, before halting his exhausted men so they could rest and water their horses at the river Lycus. At midnight, they moved on toward Arbela, where they later found Darius' chariot, weapons, and treasure. Parmenion occupied the Persian camp, capturing their baggage train of camels and their elephants (curiously little is mentioned of the elephants role in the battle).

Victory

In all, Arrian states that over 300,000 Persians were killed and more captured, with only 100 Macedonian dead. These figures are almost certainly grossly inflated. A more conservative estimate is 40,000 Persian dead, and Alexander himself claimed that his army suffered about 500 killed and 5,000 wounded. With widely fluctuating casualty lists, it is virtually impossible to determine how many lost their lives or limbs at Gaugamela.

It is unknown whether it was Alexander's deliberate intention to provoke Darius into removing men from his centre to counter the Macedonian outflanking movement, thereby creating a fatal gap. But his actions would suggest it, and Alexander was quick to seize the opportunity when it occurred.

Although Darius still lived, his authority was a tenuous shadow of former times, and he would eventually be murdered by his cousin Bessus. With his defeat, and after resting his troops for a month at Arbela, the way was now open for Alexander to march on the heartland of Achaemenid Persia.

The battle was portrayed in the 2004 movie Alexander, although the depiction of the phalanx opening its ranks and creating 'boxes' in which to trap Darius' chariots was invented by Captain Dale Dye, military trainer for the cast, and the scene where Cleitus the Black saves Alexander's life actually took place at the Battle of the River Granicus.