The most important cultural value in ancient Egypt was harmony; known to the Egyptians as ma'at. Ma'at was the concept of universal, communal, and personal balance which allowed for the world to function as it should according to the will of the gods. Throughout most of Egypt's history this belief served the culture well. The king's primary duty was to uphold ma'at and maintain balance between the people and their gods. In doing so, he needed to make sure that all of those below him were well cared for, that the borders were secure, and that rites and rituals were performed according to the accepted tradition. All of these considerations provided for the good of the people and the land as the king's mandate meant that everyone had a job and knew their place in the hierarchy of society.

At certain times, however, the king found it difficult to maintain this harmony due to the press of circumstance and a lack of resources. This situation is clearly apparent toward the end of each of the three periods known as “kingdoms” and sometimes during but an especially interesting incident during the New Kingdom (c. 1570- c.1069 BCE) stands out because it occurred before the actual decline of New Kingdom power and, according to some scholars, marks the beginning of the end: the first labor strike in recorded history.

Background

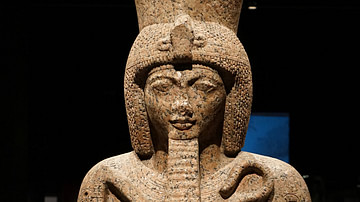

Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) is considered the last good pharaoh of the New Kingdom. He defended Egypt's borders, navigated the uncertainty of changing relations with foreign powers, and had the temples and monuments of the country restored and refurbished. He wanted to be remembered in the same way that Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) had been - as a great king and father to his people – and early in his reign he succeeded in this. Egypt was not the supreme power it had been under Ramesses II, however, and the country Ramesses III ruled over had suffered a loss in status with attendant diminishing resources from tribute and trade.

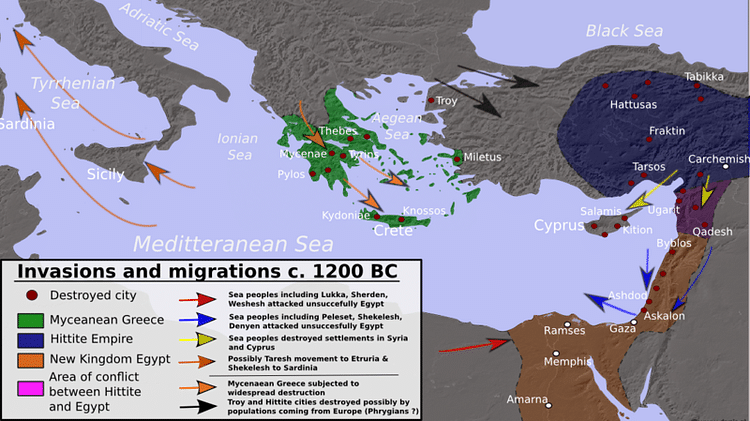

In 1178 BCE the confederation known as the Sea Peoples mounted a massive invasion of Egypt which further strained the country's resources. The Sea Peoples had tried to conquer Egypt twice before, during the reigns of Ramesses II and his immediate successor Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE). Both of these kings had successfully defeated them but the army advancing on Ramesses III was much larger and his resources fewer.

Still, he mounted a strong defense of the country, fortifying strongholds along the borders and throughout the interior and launching his navy against the invading ships. He initiated a nationwide conscription from every district in the land to build up the military and conferred with his generals on the best way to defeat the enemy at sea: by drawing them close enough to shore at the mouth of the Nile so they would be within range of Egyptian archers but keeping them far enough away to prevent a landing.

His plan worked and the Sea Peoples were defeated in the sea battle, many of them slaughtered under the hail of arrows from the shore or drowned when their ships were capsized, but the Egyptian losses in the land engagement seem to have been quite high. Ramesses III's inscriptions regarding the event only focus on the brilliant sea victory at the mouth of the Nile and are silent on the land battle. There may have been many more Egyptian lives lost than the official records cared to admit and this resulted in a loss of labor on the country's farms and a slimmer harvest, fewer merchants to trade goods, and a loss of those in other occupations which kept the economy strong.

Ramesses III had won a stunning victory, however, on par with the reports of Ramesses II's triumph at Kadesh in 1274 BCE. He followed this up, in keeping with the principle of ma'at, by refurbishing the temples and monuments of the land through a grand tour from the south to the north. During this time he oversaw adjustments in taxes, made sure that officials were performing their jobs competently, and corrected the performance of rituals which were not in line with tradition. In all of this, the pharaoh was attempting to elevate Egypt to the status it had known at the height of the New Kingdom but even he must have known it was not enough. The cost of the king's entourage as it toured Egypt would have been an incredible expense and drain on an already strained treasury and the improvements and renovations he ordered placed even greater demands on resources.

He, therefore, ordered a number of expeditions to foreign lands in trade and military conquest, all of which were quite successful. His greatest feat in this regard was the two-month expedition to the Land of Punt – a country rich in resources which had not been visited by the Egyptians since the time of Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE). These efforts should have replenished the treasury but, somehow, did not. Scholars offer differing theories as to why this happened but most agree the central problem was three-fold: a loss of labor from casualties in the war and the incredible expense in repelling the Sea Peoples, corrupt officials who diverted resources to their own accounts, and poor harvests owing to weather conditions.

The Strike

For over 20 years Ramesses III had done his best for the people and, as he approached his 30th year, plans were set in motion for a grand jubilee festival to honor him. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson notes:

The court now looked forward to the king's thirty-year jubilee, determined to stage a celebration worthy of so glorious a monarch. There would be no stinting, no corners cut. Only the most lavish ceremonies would do. It was a fateful decision. Beneath the pomp and circumstance, the Egyptian state had been seriously weakened by its exertions. The military losses of 1178 were still keenly felt. Foreign trade with the Near East had never fully recovered from the Sea People's orgy of destruction. The temples' coffers might be full of copper and myrrh, but their supplies of grain – the staple of the Egyptian economy – were gravely depleted. Against such a background, the jubilee preparations would prove a serious drain on resources. (334)

The troubles began in 1159 BCE, three years before the festival, when the monthly wages of the tomb-builders and artisans at Set-Ma'at (“The Place of Truth”, better known as Deir el-Medina) arrived almost a month late. The scribe Amennakht, who also seems to have served as a kind of shop steward, negotiated with local officials for the distribution of grain to the workers but this was only a temporary solution to an immediate problem; the underlying cause of the failure in payment was never addressed.

Instead of looking into what had gone wrong and trying to prevent it from happening again, officials dedicated themselves to preparation for the grand festival. The payment to the workers at Deir el-Medina was again late and then again late until, as Wilkinson writes, “the system of paying the necropolis workers broke down altogether, prompting the earliest recorded strikes in history” (335). The workers had waited for 18 days beyond their payday and refused to wait any longer. They lay down their tools and marched toward the city shouting “We are hungry!” They first demonstrated at Ramesses III's mortuary temple and then staged a sit-in near the temple of Thutmose III.

The local officials had no idea how to deal with the situation; nothing like this had ever happened in the history of the country. Ma'at applied to everyone, from the king to the peasant, and everyone was expected to recognize his or her place in the scheme of the universe and act accordingly. Workers rising up and demanding their pay was quite simply an impossibility because it violated the principle of ma'at. With no understanding of how to deal with the problem, officials ordered pastries delivered to the striking workers and hoped they would be satisfied and go home.

The pastries were not enough, however, and the next day the men took over the southern gate of the Ramesseum, the central storehouse of grain in Thebes. Some broke into the inner rooms demanding their pay and the temple officials called the chief of police, a man named Montumes. Montumes told the strikers to leave the temple and return to their work but they refused. Helpless, Montumes withdrew and left the problem for the officials to resolve. The back pay was finally handed over after negotiations between the priest-officials and the strikers but no sooner had the men returned to their village than they discovered their next payment would not be coming.

Again the workers went on strike, this time taking over and blocking all access to the Valley of the Kings. The significance of this act was that no priests or family members of the deceased were able to enter with food and drink offerings for the dead and this was considered a serious offense to the memory of those who had passed on to the afterlife. When officials appeared with armed guards and threatened to remove the men by force, a striker responded that he would damage the royal tombs before they could move against him and so the two sides were stalemated.

By this time the men were no longer simply striking over the late payments but what they saw as a serious breach of ma'at. The king was supposed to take care of his people and that meant making sure that officials who oversaw payments did so correctly and in a timely manner. It was now going on three years since the strikes first started and the situation had not changed: the workers would not receive their pay, they would then go on strike, the officials would find the means to pay them, and the same scenario would be repeated again the next month. The tomb-workers and artisans claimed that injustice of the highest order was being perpetrated and they wanted that situation addressed.

The local government, however, still had no understanding of how to handle the problem. It was their responsibility to maintain order and, especially with the jubilee coming up, keep the peace and uphold the dignity of pharaoh. They could not send official word to the capital that the workers of Thebes refused to do their jobs or they could possibly face execution for failing to do their duty; so they did nothing. In keeping with the traditions of the culture, they should have sent word to the vizier who would then have looked into and corrected the problem. The vizier did, in fact, come to Thebes at about this time in order to collect statues for the jubilee celebration but there is no indication he was told anything about the striking workers.

The jubilee in 1156 BCE was a great success and, as at all festivals, the participants forgot about their daily troubles with dancing and drink. The problem did not go away, however, and the workers continued their strikes and their struggle for fair payment in the following months. At last some sort of resolution seems to have been reached whereby officials were able to make payments to the workers on time but the dynamic of the relationship between temple officials and workers had changed – as had the practical application of the concept of ma'at – and these would never really revert to their former understandings again. Ma'at was the responsibility of the pharaoh to oversee and maintain, not the workers; and yet the men of Deir el-Medina had taken it upon themselves to correct what they saw as a breach in the policies which helped to maintain essential harmony and balance. The common people had been forced to assume the responsibilities of the king.

Significance

The strikes of the tomb-workers and artisans were especially influential because these men were among the highest paid and most respected in the country. If they could be treated this poorly, the reasoning went, then others should expect even worse. The influence of the strikes was also so great because these workers had the most to lose, were all very aware of the principle of ma'at and their duty to it, and yet chose to stand up against a governmental practice which they felt was unjust. What began as a complaint over late wages turned into an action protesting corruption and injustice. Toward the end of their strikes the workers were no longer chanting about their hunger but about the larger issue:

We have gone on strike not from hunger but because we have a serious accusation to make: bad things have been done in this place of Pharaoh. (Wilkinson, 337)

The success of the tomb-worker/artisan strikes inspired others to do the same. Just as the official records of the battle with the Sea Peoples never recorded the Egyptian losses in the land battle, neither do they record any mention of the strikes. The record of the strike comes from a papyrus scroll discovered at Deir el-Medina and most probably written by the scribe Amennakht. The precedent of workers walking away from their jobs was set by these events and, although there are no extant official reports of other similar events, workers now understood they had more power than previously thought. Strikes are mentioned in the latter part of the New Kingdom and Late Period and there is no doubt the practice began with the workers at Deir el-Medina in the time of Ramesses III.