Lacquer was a popular form of decoration and protective covering in ancient China. It was used to colour and beautify screens, furniture, bowls, cups, sculpture, musical instruments, and coffins, where it could be carved, incised, and inlaid to show off scenes from nature, mythology, and literature. Time-consuming to produce, Chinese lacquerware became highly sought after by those who could afford it and by neighbouring cultures.

Materials & Techniques

Lacquerware describes objects made of wood, metal, or just about anything similar which have been covered in a liquid made of shellac or melted resin flakes dissolved in alcohol (or a synthetic substance), which forms a hard protective smooth coating when dry which remains relatively light in weight. The ancient Chinese artists used the sap of the tree Rhus vernicefera (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), which was native to eastern and southern China and was sometimes referred to as the 'Lacquer Tree'. The resin is drained from a cut in the living tree and becomes an opaque white liquid on contact with the air. Lacquer existed in many colours by adding certain chemicals to the resin, for example, black was made by adding carbon, yellow by adding ochre, and a brilliant red was achieved by mixing in mercuric sulphide (aka cinnabar). These were the three most popular colours in ancient Chinese lacquer painting.

The resulting lacquer, when dried slowly in humid conditions, is remarkably resistant to heat, damp, and chemicals. For this reason, lacquer was often used to coat and protect goods of more perishable material which might be easily damaged such as bamboo, silk, and wood. Lacquer can quickly degrade, though, if it cracks, and this has led to a scarcity of finds in ancient tombs and other buried contexts.

As the lacquer is very thin when applied it requires many coats to provide an even finish, but an advantage is that the lacquer can be used to cover almost any type of surface, uneven or otherwise. The preceding coat must be absolutely dry and be highly polished before applying the next one, with some objects having as many as 100 such layers, illustrating that the production of lacquerware was a time-consuming and expensive business.

By the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) a new technique became popular where a wooden or textile base material was repeatedly covered in lacquer until it was thick enough to be sculpted and carved. If different colours of lacquer were used in different applied layers then cutting through them could reveal the contrasting colours to pick out designs. Another effect was to have the surface and lowest level of lacquer in the same colour but have the sides of the cut display a marble effect from the use of different coloured intermediate layers.

The Guri technique creates schematic scroll designs by cutting through layers of different colours, and the deep cuts are often bevelled. Sometimes fine gold wiring or leaf was used as an inlay in carved lacquer or studs of semi-precious material such as turquoise, mother-of-pearl and ivory were pressed into the surface. Intricate linear and floral designs, images of humans, animals, birds and mythical creatures, and even sculpted landscape scenes were thus rendered in lacquer. Although great artistry was employed in lacquerware, it was not common for pieces to be signed by the artist until the 14th century CE.

Lacquerware Evolution

The earliest Chinese lacquerware yet discovered dates to the Late Neolithic period (3rd millennium BCE) and comes from the Hemudu site in a waterlogged area of the lower Yangtse region which has preserved many such artefacts. Production of lacquerware continued into the Bronze Age of the 2nd millennium BCE when it began to be traded to other areas of China which did not have the Rhus vernicefera tree.

From the 5th century BCE and the Warring States Period lacquer production greatly intensifies and even small-scale burials have some lacquerware - typically cups and bowls - placed in them while larger tombs can have hundreds of examples. This suggests that production scale had increased and the product had become affordable to even those with a modest income. The artists of the Chu state were particularly imaginative and produced distinctive lacquered sculptures of mythical creatures which may have acted as tomb guardians.

By the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) lacquer was being used on cups, bowls, small boxes, figure sculpture, musical instruments and their stands, bows (to make the wood and bindings waterproof), wooden wall panels showing narrative scenes, and fans. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) the state sponsored and supervised the production of lacquerware which now had different schools of lacquer art producing common forms but with recognisably distinct designs.

Lacquerware Forms

The most common lacquered goods were shallow stemmed cups (circular or oval) with varieties of handles, cups shaped into birds, beakers, and bowls (sometimes with winged rims) which often imitated the decorative designs seen in contemporary bronze work and embroidery. Typical motifs include lozenge patterns, monsters, stylistic dragons, circles, close spirals, zig-zags, triangles and curved lines and asymmetrical shapes to fill the blank areas in-between. Small lacquered boxes were also popular and could be round, rectangular or L-shaped. A third main group in the lacquer artist's armoury was wooden animal sculptures depicting tigers, deer, peacocks, cranes, and monsters with antlers and protruding tongues, amongst others. Statues of Buddhist figures which appeared in temples would come to be lacquered, too, especially during the Tang Dynasty.

Paper or wooden screens were an ideal medium for the lacquer worker. Painted on both sides with scenes and sometimes also with extracts from famous texts, they were used not only to divide living space in private homes but also in tombs to surround the coffin of the deceased. One such example is from the tomb of Sima Jinlong, a Tuoba ruler of Wei, the northern Chinese state, who died in 484 CE. The lacquered screen was divided into four sections arranged vertically and had scenes and text from the 1st-century BCE Lienu zhuan ('Biographies of Exemplary Women'). The screen is 80 cm high (it was not necessary for screens to be taller because people then sat on mats on the floor) and has the figures and text in yellow on a bright red background.

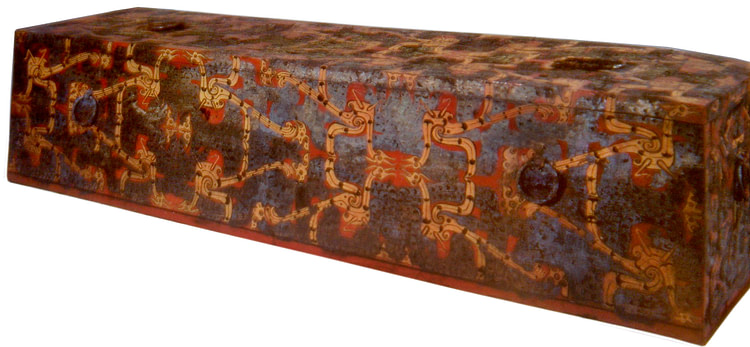

Coffins for those who could afford them were lacquered and an outstanding example comes from the 4th century BCE tomb at Baoshan in Hubei Province. The rectangular coffin was the innermost of three and is entirely covered in black lacquer with 72 yellow and red depictions of interconnected dragon snakes and a similar number of mythical birds. It is currently on display in the Hubei Provincial Museum, China.

Musical instruments were lacquered both to protect them and to add decoration. One famous pipa, a type of lute, from the 8th century CE has a Buddhist landscape painting with mountains and rivers. It is thought to be one of the earliest such depictions. The instrument is now in Shosoin, Nara, Japan and is one of many such items given as gifts or traded and it illustrates the wide appeal of Chinese lacquerware across East Asia.

Small items of furniture such as low tables were frequently lacquered and carved with decorative designs. A superb example, albeit late (Ming Dynasty, 15th century CE), is a table of red carved lacquer covering a wooden core, which is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The techniques of working the lacquer did not change over the centuries but later artists did eventually become more ambitious, and by the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1644-1912 CE) huge scenes were being carved in high and precise relief with many different levels of perspective.