The chariot was used in Chinese warfare from around 1250 BCE but enjoyed its heyday between the 8th and 5th century BCE when various states were constantly battling for control of China. Employed as a status symbol, a shock weapon, to pursue the enemy, or as transport for archers and commanders, it was used effectively in many battles of the period. Eventually, with the rise of lighter and more mobile infantry and especially following the introduction of cavalry, its limitations were more exposed with the consequence that the chariot became relegated to a peripheral role in warfare from the 3rd century BCE.

Shang Chariots

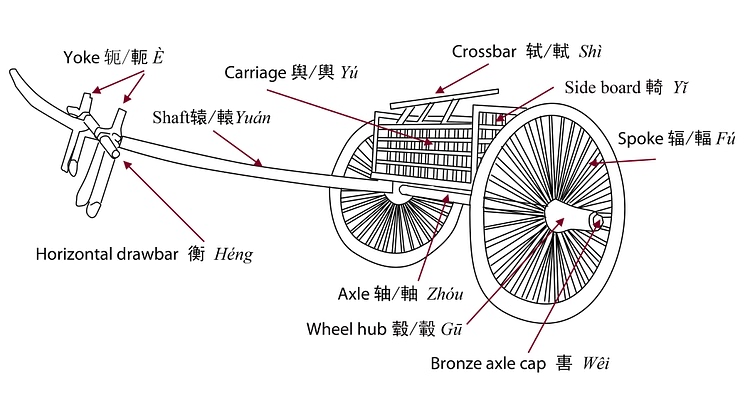

Chariots first came into use from the mid-13th century BCE and were probably introduced from Central Asia. According to Chinese legend, in contrast, they were invented closer to home by the Yellow Emperor or one of his ministers Hsi Chung. That they were imported is evidenced in the absence of any significant evolution, the absence of precursor vehicles such as carts and wagons, and that the earliest chariot finds are already relatively complex in design. A rectangular walled platform was attached over a single transverse axle which the wheels revolved around. A single draught pole running from the centre of the cab was then harnessed to the horses.

At first, their use in the Shang state (and some neighbours) was limited with only a few nobles employing them in battle, and their production, like weapons in general, was controlled by the state. Shang chariots were usually drawn by a pair of horses, more rarely by four, which were small stocky creatures controlled by a rope bridle and bit, which evolved into leather versions and then bronze. Chariots had two wheels, which could be up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in diameter with 18 spokes being the commonest number. The wheels were thus much higher than 2ndmillennium BCE chariots of Mycenae and the Near East.

Made of wood, bamboo, rattan and cane with some bronze fittings such as parts of the yoke and axle, they had an open front and low sides sometimes topped by a guard rail. The back was not open as in chariots in other cultures but had a gap left to mount the vehicle. A chariot crew (ma) consisted of the driver, an archer (who typically stood on the left side) and sometimes a third soldier armed with a spear or knife-axe (on the right side). It is interesting to note that most burial sites with chariots have only two people buried with them.

Chariots from this period have been found in 25 separate tombs where they were buried along with their two horses, equipment and rider which indicates the high status of the deceased. In this early period, it is important, then, to note that chariots were employed much more for ceremonial purposes, to give prestige to rulers, and as hunting vehicles than they were as weapons of war. One final use of chariots was the gruesome punishment for crimes like arson with the guilty being tied to and ripped apart by two chariots driving in opposite directions.

Western Zhou Chariots

During the Western Zhou (Chou) period (c. 1046-771 BCE) chariots developed larger wheels with more spokes and a curve away from the hub, increasing their strength. Teams of four horses became more usual than pairs and the whole vehicle received lavish decoration using cowrie shells and bronze fittings. Riders now wore chest and arm armour made from bronze, leather scales or lacquered (Sumatran) rhino and buffalo hides while the horses were protected by tiger skins with bronze additions. The extra weight which resulted in these developments would have reduced the mobility of the chariot and it is possible they were now largely used to impress and demoralise the enemy while commanders used them to better coordinate their troops.

The Western Zhou army had around 3,000 chariots at its peak to complement its 30,000 infantry. Chariots were arranged, as during the Shang, in corps of 25 subdivided into units of 5. Chariots continued to be buried with the elite in a ceremony of conspicuous consumption designed to impress. One grave pit at Liulihe of the Yan state contained 42 horses and their chariots.

Eastern Zhou Chariots

In the Eastern Zhou period (771-226 BCE) the hundreds of small states in China were gradually consolidated into eight major states. As these rivals battled for territory the power and threat of their armies were measured in how many war chariots they could field in battle. The fierce competition ensured that states invested heavily in bulking up their chariot armies. For example, in 632 BCE the Tsin had 632 chariots but only a century later they boasted 4,900. In 720 BCE the Ch'i had 100 chariots but this rose to 4,000 by the early 5th century BCE.

Chariots continued to improve in design with wheels now having up to 26 spokes, the central pole was shortened to give greater stability, and the cab was covered in hardened leather for extra protection. Sometimes chariots had a canopy to deflect arrows, sported banners, and had lethal serrated bronze blades attached to their wheel hubs. Four horses and the three-man crew continued to be the norm but the excessive decoration of the Western Zhou chariots largely disappears.

Chariots were manufactured for different purposes - lighter ones for speed to pursue a fleeing enemy or heavier and better-armoured ones for direct assaults on entrenched enemy positions. One specialised chariot of the period was the crow's nest chariot or ch'ao-ch'e which had a higher chassis, reinforced wheels, and a tower on its cab so that one man - sometimes even the army commander himself - could better view the battlefield and pass on orders to the flag wavers who communicated manoeuvres on the ancient Chinese battlefield.

The Luiu-t'ao (Six Secret Teachings), the 5th-3rd-century BCE military treatise, describes the necessity for chariot warriors to be the best and fittest in the army:

The rule for selecting warriors for the chariots is to pick men under forty years of age, seven feet five inches [modern: 5 ft 7 in.] or taller, whose running ability is such that they can pursue a galloping horse, race up to it, mount it, and ride it forward and back, left and right, up and down, all around. They should be able to quickly furl up the flags and pennants and have the strength to fully draw an eight-picul crossbow. They should pracitce shooting front and back, left and right, until thoroughly skilled. They are termed 'Martial Chariot Warriors.' You cannot but be generous to them. (in Sawyer, 2007, 100)

Deployment & Tactics

Chariots were typically formed into units of five and deployed either separately or with each chariot accompanied by its own contingent of infantry. They could be lined up in single file along the front of the infantry lines prior to battle or grouped all together in the dead centre. A commander might use a group of chariots as a shock weapon and charge a specific area of the enemy's formation or use them in a feint attack to disrupt the enemy's own manoeuvres or in a rapid ambush.

A commander had to be careful of his terrain when employing chariots as they were liable to get bogged down in wet conditions or break their axles if the field of battle was pitted with holes and rocks - there are cases when commanders prepared the field by filling the larger holes. An added limitation was the manoeuvrability of the vehicles. With a fixed axle and the horses tied to a draught pole in such a way that they could not move sideways, a chariot needed a large space to make significant turns. About turns or retreats must have been chaotic, exposing both horses and riders to infantry and archer attack. There are many instances in accounts where riders are speared or dragged from the chariot by infantry and wheels are smashed by jamming spears between the spokes when a chariot slowed to turn. For this reason each chariot usually had its own small infantry unit to protect it. Chariot counter-measures could be taken by the enemy, too, such as digging concealed pits and ditches in the battlefield or scattering caltrops (clusters of metal spikes) to incapacitate the horses.

Chariots may not always have been used to directly confront the enemy but kept as a means to take troops to the battlefield, offer the general and unit commanders better mobility and visibility of what was going on in the chaos of battle, or act as a mobile platform for archers to fire on the enemy from a distance (although the jostling of the vehicle would have made accurate fire extremely difficult). Finally, and probably as a last resort, chariots could be arranged to form a defensive wall behind which beleaguered troops could make a better defence just as settlers did with their wagons in 20th-century Western films. Several examples of such a tactic being employed exist, including with success against a numerically superior enemy.

The Liu-t'ao has this to say on the deployment of chariots:

For battle on easy terrain five chariots comprise one line. The lines are forty paces apart and the chariots ten paces apart from left to right, with detachments being sixty paces apart. On difficult terrain the chariots must follow the roads, with ten comprising a company, and twenty a regiment. Front to rear spacing should be twenty paces, left to right six paces, with detachments being thirty-six paces apart. (in Sawyer, 2011, 371)

Sometimes, as in the battle of Pi in 595 BCE between the Ch'u and Tsin, skirmishes between chariot units would go on for days before the infantry engaged each other. In the Battle of Cheng in 713 BCE between the northern Jung and Cheng the latter used their chariots to make a false retreat and then returned to surround the enemy which had become disordered in their pursuit. In the battle at Ch'en-p'u in 632 BCE between the Tsin and Ch'u, the commander, Duke Wen of Tsin, was able to surprise the enemy with his troop movements by shielding them under a cloud of dust raised by having his chariots drag branches behind them over the dry terrain. In another imaginative tactic employed by a Tsin commander, who faced the Ch'i again in the battle of P'ing-yin in 554 BCE, chariots were filled with dummies and only one rider to make it appear the army was much larger than it was. The ruse worked as the Ch'i commander withdrew thinking himself greatly outnumbered.

Decline in Use

The Zhou period had been the golden age of the chariot and never again would they be used in such great numbers. However, that is not to say that they had always been used effectively. One infamous loss was in 613 BCE when a peasant revolt in the Tsu state overthrew its rulers. An army was sent by allies which included 800 chariots but the peasant army was victorious.

The same problem hit chariot warfare just as it had in other cultures from Greece to Carthage: chariots needed relatively flat terrain and space to manoeuvre or they could easily be outflanked by a more mobile enemy infantry force no longer weighed down by bronze age armour or rigidly deployed in only three forward-moving divisions. There are episodes of chariots still being employed as useful mobile units of archers or even as a kind of artillery with winched crossbows mounted on them. In addition, literature continued to expound the noble virtue of heroes like Lang Shin riding their glorious chariots fearlessly into the enemy. Nevertheless, the reality was that from c. 500 BCE the sword was replacing the bow and spear and better infantry deployment had reduced the effectiveness of chariots on the battlefield.

When cavalry was introduced in 307 BCE, the chariot's days as an effective weapon were seriously numbered even if armies such as those of the Ch'in empire (221-206 BCE) employed them in smaller numbers and they are present in the Terracotta Army of Shi Huangdi (d. 210 BCE) with some groups of chariots accompanied by larger units of cavalry while others seem to function as field transport for groups of officers. In the 2nd century BCE, the Han continued to field them, too, but they seem to have been the exception when it came to chariot use. In general, just as the Egyptians and Mesopotamians had discovered a thousand years before, the chariot's limitation of manoeuvrability on the battlefield and the arrival of more dynamic military encounters relegated it to a minor role in ancient Chinese warfare.