Athens is mostly associated with its ancient past rather than its modern turbulent state of the latest two hundred years. While walking the centre of the luminous city, the visitor can easily observe both ends of Hellenic culture. The city offers plenty of ancient examples in every corner, the visitor must only roam aimlessly in the narrow alleys of the old town, and they will stumble upon these details that paint the picture of a thriving ancient Metropolis. On the other hand, the city's modern history has produced a culture that reflects the recent two centuries of Greek independent evolution and radiates taste and nobility.

![The Parthenon [Rear View]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/750x750/6800.jpg?v=1732959733)

Though Athens is a big city, its historical centre is walkable, which makes it easy for the visitor to enjoy. I visited the city for a 3-day-long weekend which practically only gave me two full days to visit everything I wanted; a challenging task but certainly not impossible.

ODEON of Herodes Atticus

My visit could not start anywhere else other than the world-famous Acropolis in Athens. On a sunny Saturday morning, I set eyes at the rear of the theatre of Herodes Atticus (aka Herod the Attic). If a visitor is not sure what they are looking at, the structure bears a resemblance to Roman aqueducts, and since Athens was not only part of the Roman empire but also in the heart of Emperor Hadrian, it is easy to make this mistake. But, of course, it is not an aqueduct, it is the building that housed the tragedians, comedians and actors' equipment and preparation activities. It is what we would call today 'backstage'.

Propylaea

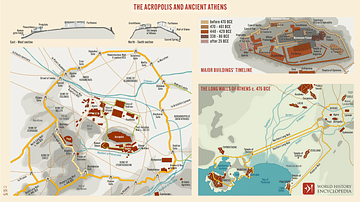

Next stop would be the main entrance to the Acropolis, the Propylaea. A little bit of history is due at this point. The Acropolis of Athens is a renovation. It was not always like it is today. During the Greco-Persian wars Athens was sacked and the temples of the Acropolis burned to the ground. Pericles was the one that commissioned the rebuilding of Acropolis, employing the greatest architects and sculptors of his time. The project was led by Phidias, while Parthenon itself was designed and built by the architects Ictinos and Kallicrates.

The Propylaea is constructed using Pentelic marble from hills neighbouring Athens. Its architecture is similar to the rest of the Acropolis, typical of ancient Greek structures of the same type but infused with the extravagance that the golden age of Greece provided. It was used many years later as a pattern for the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and the Propylaea in Munich.

Standing on the stairs of Propylaea, there is only one way the visitor's head turns; and that is up. Up to the Propylaea themselves and the temple of Athena Nike (Athena Victory); a small but imposing structure, probably one in the best condition with regards to delamination. In the Greek language, the word 'Propylaea' means 'before the gates'. Once the visitor goes through the gates of the Acropolis and into the central plateau, the two most famous temples rise to greet them; the Parthenon, the main temple of Athena, and the Erechteion, a temple dedicated to both Athena and Poseidon. I decided to leave Parthenon last due to its fame but also because, despite its size, it is a much more straightforward structure.

Erechteion

The Erechteion has a rather odd name, even by Greek standards. Its lady-columns, the Caryatids, are closely related to the origins of the name. The Caryatids are 'the maidens of Karyai' a small town in the Peloponnese with a temple to the goddess Artemis. The Caryatids were her servants. The Erechteion comprises two sectors. The main temple and a smaller chamber called Kekropion. Legend has it that the ancient semi-legendary Athenian kings of the Bronze Age, Erechtheus and Cecrops are buried underneath the temple, under their respectively dedicated chambers. More specifically, the box-shaped protruding structure that houses the Caryatids is on top of the actual grave of King Erechtheus.

The Erechtheion has had many uses over the ages, hence its relatively well-preserved state. Built in 421 BCE, it was initially a temple, as mentioned before. Following the establishment of Christianity as the state religion by the Roman Emperor Constantine I the Great, the Erechtheion became a Christian church. This use held until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 CE. After that, it became the house of the Ottoman commander of Athens and his harems until 1830 CE. Of course, one cannot have a Greek monument without a little bit of controversy. The situation started in 1801 when a British nobleman, Lord Elgin, removed one of the Caryatids along with several parts of the Parthenon's pediment, to decorate his mansion in Scotland. Elgin's people later sold the pieces to the British Museum where they are today. The debate over the Elgin Marbles is a subject of much discussion and controversy between the Greek and British states.

Parthenon

Moving on to the Parthenon, I immediately became sad after looking at it. Despite its magnificence, its size, its importance, and its worldwide radiance, it is not a restored temple. The damage it has sustained through the ages is unspeakable. The story of this extensive damage goes back to the Greek War of Independence during the 1820's CE. Turkish ships laid siege to Athens that was occupied by Greek fighters. They bombarded of the area, resulting in the destruction of much of the Parthenon. It is a shame to see it in such condition, and it makes me wonder what it would look like if it were fully restored, even using modern materials in the place of the destroyed ones.

An excellent piece of structural engineering history that the Parthenon provides is the use of reinforcement inside the column. The round pieces of marble that make the columns are not discs but rather rings. Every piece has a hole in the middle that used to contain lead rods that acted as reinforcement, thus increasing the effectiveness of the load bearing elements of the temple, especially in the instances of earthquakes that were and are so common in Greece.

Additional to the temples of the golden age of Athens, on the Acropolis, the visitor can admire what remains of the altar of Octavian Augustus; an offering to the divine from the first of the Roman emperors to one of the most sacred sites of the ancient world.

Theatre of Dionysus

After concluding my tour of the Acropolis, I headed back outside from the Propylaea and descended towards the remains of the Temple of Themis and the Theatre of Dionysus. Several scribed stones are on display along the way, and I tested my memory on the attic dialect of ancient Greek, trying to figure out the meaning of the inscriptions. I might not have been able to comprehend the full meaning, but I got a decent understanding. These inscriptions were written 2500 years ago, and that fills me with awe about this living and evolving language.

The walk led me in front of the Theatre of Dionysus, where one can observe the 'VIP' seats of the theatre, with the names of the people inscribed on the seats.

Acropolis Museum

Within walking distance from the Theatre of Dionysus, it is the entrance of the new Acropolis Museum, about which I had heard so much. I must say that three elements of the museum caught my attention. The first is the original Caryatids that stand on an interior balcony, where the visitor can enjoy from a very close (touching) distance.

The second breath-taking exhibit of the museum is on the top floor. It is none other than the full pediment of the Parthenon, with the Titanomachy described at a succession in every piece of it. I needed a significant amount of time to go through all the parts and understand the depicted scenes, but it was an incredible sight to behold, especially if imagined painted. Finally, the third characteristic that adds to the whole experience is the top floor's view. The Acropolis itself with all its magnificence fills the window view, and it is just awe-inspiring.

Roman Forum

To be completely honest, I was not acutely aware of the extent of the Roman Agora in Athens. I was surprised to see a large complex of buildings with different uses and meanings that opened a new view of the city in my eyes. Emperor Hadrian did an excellent job extending the city, leaving a remarkable footprint. Before entering the site, the visitor must cross a small bridge over the urban railway and while on the bridge, on the right-hand side, the remains of the altar of the twelve gods are visible. I entered the site and headed to the left. My first stop was the Stoa of Attalos. A small Roman rotunda is the first thing you see and right next to it a very long building that is the Stoa and houses the Agora Museum.

I continued walking the Panathenaic Way towards the church of the Holy Apostles, and with the Library of Pantainos on my left, I headed right towards the Gymnasium. I descended towards the Odeon of Agrippa on my way to the Temple of Hephaestus. Passing from the Bouleuterion and the Metroon I was looking at the Stoa of Zeus; all buildings formed something like an entrance to the Temple. At the entry to the road leading upwards to the Temple stands the statue of Emperor Hadrian.

The Temple of Hephaestus is smaller than the Parthenon but much better preserved. The visitor can see the inside of the temple with the roof and all, to get a complete idea of a typical Greek temple's interior architecture.

I descended from the temple via the same road and walked towards the exit of the site passing by the remains of the Temple and Altar of the god Ares.

Panathenaic Stadium

Later in the afternoon, I went to see the Panathenaic Stadium, which has a long and fascinating history covering not only the ancient festival but it holds a world record in modern times. It was first set up as a racecourse for charioteers at some point in the 6th century BCE. In 330 BCE the Architect Lycourgos built the first version of the stadium with limestone, whereas in 144 CE the stadium was renovated using marble by Herod Atticus. The festival, the Great Panathenaia, was a mixture of ceremonial, athletic, and cultural competitions that were held every four years and lasted for about a week. The Panathenaic games continued until the reign of Emperor Theodosius I, who banned all ancient pagan events to suppress the respective pagan religions in favour of Christianity.

In the modern era, the stadium was home to the basketball team of AEK Athens. In 1969 FIBA European Cup Winner's Cup final, AEK Athens competed against Slavia Prague. Watching the final in the stadium were 80000 seated spectators and 40000 standing ones, making this the basketball game with the most attendance in history. The stadium still holds this record.

Temple of Olympian Zeus

Moving forward, I headed west towards the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The temple was the biggest in ancient Greece, and the remains are a testament to this regarding height and length, but it is a shame that only a few columns remain.

In front of the entrance to the Columns of Olympian Zeus, the visitor can find the Arch of Hadrian. The emperor loved Athens, and you can see this all around the city. Opposite the monument of, in front of the Byzantine Orthodox Christian Church of Saint Catherine's front garden, there are some ancient ruins. Apparently, these ruins are the remains of the Roman baths built by Emperor Hadrian. On the street that bears the name of Lysicrates, I noticed a tavern with the Hellenised name of the emperor, 'Adrianos'.

Prison of Socrates & Ecclesia of DEMOS

The following day, I decided to go to the hill of Philopappos, a forested hill with a pleasant feeling and peaceful walks. The first notable historical site is the prison of Socrates, the place where he was held before his execution by hemlock (Conium) poisoning in 399 BCE.

On the top of the hill, I stood in the very place that the meetings of the Ecclesia of Demos took place, complete with the podium of the orators and the best view of the monuments of the Acropolis and Athens in general.

I headed downhill leaving behind all the antiquities. This journey through time and the beauty that one can observe within it left me thankful for my decision to visit the place. Two days are not nearly enough to enjoy the city's history, let alone the rest of what it has to offer. On my flight home, I was left reflecting on the trip and already planning my next visit to the cradle of western civilisation. There are a few things that I missed like Plato's Academy, the temple of Poseidon in Sounion and of course more earthly indulges, taverns, bars and the beautiful seaside neighbourhoods that bring the Greek islands to the Athenians' feet.