One of the most fascinating aspects of the female pharaoh Maatkare Hatshepsut's reign (1479 - 1458 BCE) is the artwork she left behind. Art served an important purpose in Egyptian society; every statue, mural, and motif had a significant meaning. Pharaohs frequently used art as a way to disseminate information about themselves, a propaganda tool to justify their rule and emphasize their divine nature to the common people (many of whom were illiterate). Hatshepsut was no exception to this rule.

By commissioning statues depicting herself in traditionally male pharaonic poses, Maatkare Hatshepsut was trying to explain her unique situation of a woman occupying a man's job to the public in a simple, accessible way. However, the art from Hatshepsut's reign also suggests that the switch from depicting herself as fully feminine to fully masculine did not occur overnight. Elements of Hatshepsut's femininity remain evident in many of her artistic depictions, and evidence of her true gender is even observable in pieces where the king is portrayed as a man.

Biography

In ancient Egypt's long line of powerful queens and female rulers, Maatkare Hatshepsut stands out as the most successful of them all. She reigned for over 20 years, leading her people into an age of peace, stability, and prosperity. Unlike many of her predecessors and successors, there is little evidence of any major conflicts or military operations during Hatshepsut's rule. Instead of waging war, the king set out on a massive infrastructure campaign, building temples and erecting monuments across the land.

The daughter of Pharaoh Thutmose I, Hatshepsut held a number of impressive positions before proclaiming herself Pharaoh: first, she was the God's Wife of Amun, and then, upon her father's death in 1493 BCE, became Queen of Egypt by marrying her half-brother, Thutmose II. She had one child with Thutmose, a daughter named Neferure.

When Thutmose II died in 1479 BCE, Hatshepsut was presented with a dilemma. She had not borne her husband a son, and Thutmose's only male heir, Thutmose III (his son by a secondary wife), was only a toddler. Following the precedent established by a number of great queens before her, Hatshepsut assumed control of Egypt, crowning Thutmose III Pharaoh and serving as Queen Regent until the boy king came of age. Then, in 1473 BCE, Hatshepsut took a shocking next step: she proclaimed herself pharaoh of Egypt and ruled alongside Thutmose as his (senior) co-regent. As a woman occupying a traditionally male role, Pharaoh Hatshepsut needed to find a way to justify her unusual kingship in the eyes of her court and her subjects. In order to do so, Maatkare Hatshepsut turned to art.

Artistic Representations

There is a clear progression from female to male form evident in artistic representations of Hatshepsut over the course of her lifetime, with the most fascinating and unusual pieces dating from the early years of her reign. For instance, statuary from the beginning of Hatshepsut's co-regency with Thutmose III very clearly portrays the queen as fully female, donning the long, plain sheath dress of a royal Egyptian woman. However, Hatshepsut wears the pharaonic nemes headdress, typically worn only by male kings. This odd combination is evident in a red granite piece on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York: it depicts a seated Hatshepsut in female clothing wearing the nemes crown, and is inscribed with her pharaonic throne name “Maatkare” (“Truth is the Soul of the Sun”), and feminized versions of her kingly titles (“Daughter of Re,” etc). Another seated statue from this period, also at the Met, paints a similar picture. Carved from black diorite, it shows a female Hatshepsut donning the kingly khat headdress of a male pharaoh.

The next phase of Hatshepsut's statuary is where things get even more interesting. One piece depicts a seated Maatkare Hatshepsut with a distinctly female face and torso, wearing the nemes crown and sitting on a throne. However, Hatshepsut has lost the sheath dress and instead sports a short male kilt and a bare chest. Again, this piece is inscribed with her throne name and feminized versions of traditional male titles.

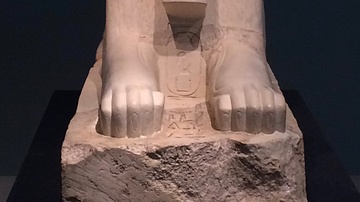

From this point forward, Hatshepsut commits to depicting herself in a fully male form. There is a collection of statues both large and small, which show Hatshepsut in devotional positions, offering to the gods. Here the pharaoh is again barechested and wearing a kilt, with no evidence of female breasts or facial features. She is wearing the nemes headdress (adorned with the royal uraeus serpent), and also sports the traditional false beard of a male pharaoh. In some cases, the female king is even shown as a sphinx, with the body of the lion and the crowned head of a man.

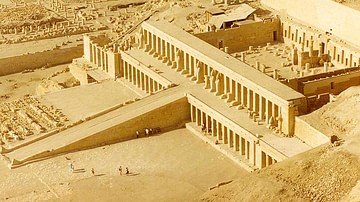

Similarly, many osiride statues of the king survive, depicting a bearded, mummified Hatshepsut as the god Osiris. Some of these pieces guard the halls of her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari to this day. Interestingly, from the remnants of ancient paint still visible on these statutes, it appears that Hatshepsut continued experimenting with her artistic depictions throughout her reign. Although fully male in form, the pharaoh had her statues painted with a unique, almost orange skin tone, a combination of the deep red ochre typical of an ancient Egyptian man and the lighter yellow complexion of a woman.

Conclusion

It is highly unlikely that the way Hatshepsut appears in official artistic pieces is how the queen looked and dressed in real life. All Egyptian art is highly idealized, each piece meant to easily convey a message about the person it represents. Maatkare Hatshepsut probably did not walk around her palace barechested and wearing a fake beard: her true gender was no secret, and she never intended it to be so. Just look at the inscriptions found on much of her statuary: “Daughter of Re,” and “Lady of the Two Lands.”

Even in pieces where she is portrayed as fully male, Hatshepsut still found ways to accent her femininity and true nature. She depicted herself as a male pharaoh simply to legitimize and help explain her rule. While there had been multiple female rulers before her, and there were no set laws against having a female king, a woman pharaoh on the throne of Egypt taking seniority over a viable male heir (Thutmose III) was still an unusual, near-inexplicable situation. By representing herself as a traditional male king, strong, youthful, and pious, Hatshepsut was explaining to her subjects that she was just as tough and fit for the throne as any of her male counterparts. Although many of her statues were destroyed and defaced after her death (most likely by Thutmose III to reinforce the ideals of male kingship and male-male succession), the art that survives from Hatshepsut's reign speaks volumes about her creativity, unconventionality, and political cunning.