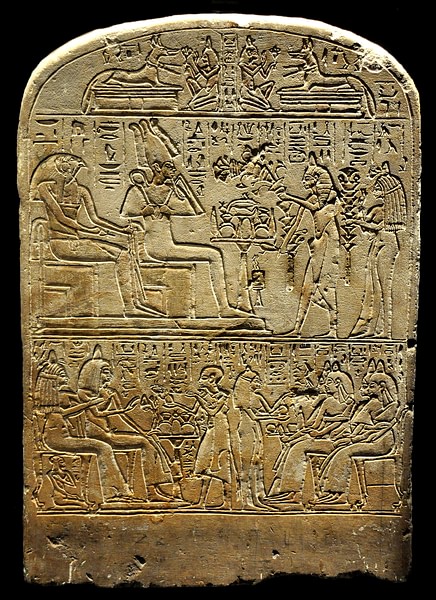

In any society, members of the community recognize they are required to restrain certain impulses in order to participate in the community. Every civilization has had some form of law which makes clear that the benefits of peaceful coexistence with one's clan, city, village, or tribe outweigh the gratification of selfish desires, and should one act on such desires at others' expense, there will be consequences. In ancient Egypt, the underlying form of the law which modified behavior was the central value of the entire culture: ma'at, (harmony and balance). Ma'at, personified as a goddess, came into being at the creation of the world and was the principle which allowed everything to function as it did in accordance with divine order.

The ancient Egyptians believed that, if one adhered to this principle, one would live a harmonious existence and, further, be assured of passage to paradise in the next life. After death, one's heart would we weighed in the balance against the white feather of ma'at, and if found heavier through selfish behavior, one's soul was denied paradise and would cease to exist. Adhering to ma'at simply meant living a balanced life with respect for one's self, one's family, immediate community, and the greater good of one's society. It also included a respect for the natural world and the animals which inhabited it and a reverence for the unseen world of the spirits and the gods.

People being what they are, however, there were many instances in which an individual would elevate his or her own self-interest above that of others, and so the Egyptians had to introduce more specific laws than simply the suggestion that one should conduct one's self with moderation and consideration for others. These laws would have been nothing more than further suggestions, however, if the authorities had no way to enforce them and so the occupation of policeman was created.

The Evolution of the Police

During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) there was no official police force. The monarchs of the period had personal guards to protect them and hired others to watch over their tombs and monuments. Nobles followed this paradigm and hired trustworthy Egyptians from respectable backgrounds to guard their valuables or themselves.

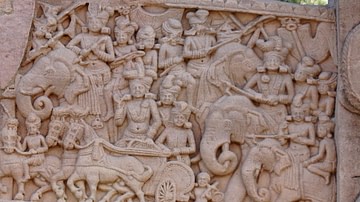

By the time of the 5th Dynasty, toward the end of the Old Kingdom, this model began to change with kings and nobles choosing their guards from among the military and ex-military as well as from foreign nations, such as the Nubian Medjay warriors. Armed with wooden staffs, this early police was tasked with guarding public places (markets, temples, parks) and often used dogs and trained monkeys to apprehend criminals.

A relief from the 5th Dynasty tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum depicts a police officer apprehending a thief in the market place with one of these monkeys. The monkey is restraining the thief by the leg as the officer approaches to arrest him. Dogs were used primarily in the same way, for apprehension, but also served in their familiar capacity as guardians. The breeds most often depicted as police dogs from this period are the Basenji and Ibizan.

The Old Kingdom collapsed and ushered in the era of the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) during which the central government was weak and the individual nomarchs (district governors) held more or less supreme power over their regions. Records from the First Intermediate Period are sparse because there was no strong central government bureaucracy to keep and catalogue them but the same basic model seems to have applied: the upper class hired private guards to protect their homes and property, and these guards were drawn from a class of society, often Nubian, with some military experience.

Bedouins were often employed to police the borders and assist in protecting trade caravans while Egyptian guards served in more domestic spheres. There was no standing army in Egypt at this time, and so these men were also posted as sentries at forts along the border, guarded the royal tombs, and served as personal bodyguards and protectors for traders on expeditions to other lands.

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) saw the creation of the first standing army under the reign of Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) of the 12th Dynasty. These soldiers were highly trained professional warriors who now were posted at garrisons along the border and were sometimes sent along with royal trade expeditions. The somewhat informal arrangement of employing warriors as guards was replaced by the development of a professional police force with specific focus on enforcing law; the new army took over most of the old guard's responsibilities.

This period also saw the creation of a judicial system which was far superior to that of the past. Previously, court cases were heard by a panel of scribes and priests who would weigh the evidence and consult with each other and their god. If one were wealthy enough, one could easily bribe this panel and walk free. In the Middle Kingdom, the position of the professional judge was created. Judges were men versed in the law and paid by the state who were so amply compensated and cared for that they were considered incorruptible. The creation of judges led to the development of courts which required bailiffs, court scribes, court police, detectives, and interrogators.

The Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE) was another era of weak central government and uneven record keeping. The Hyksos, a foreign people, held the Delta region and much of Lower Egypt and the Nubians had encroached from the south into Upper Egypt. Some of the Nubians, however, sold their services to the princes of Thebes as mercenaries in their army and as guardians for trade expeditions. These were the Medjay warriors, legendary in their own time for their skill and courage in battle. When Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos from Egypt, he employed these mercenaries in his army and afterwards, once order was restored, they formed the core of the professional police force of Egypt.

Ahmose I initiated the era known as the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) in which this police force became more organized and the judicial system as a whole was reformed and developed further. There was never any occupation which corresponded to a lawyer in ancient Egypt but the practice of allowing witnesses to testify on behalf of the accused – while an officer of the court prosecuted – became commonplace.

Police officers served as prosecutors, interrogators, bailiffs, and also administered punishments. The police, in general, were responsible for enforcing both state and local laws, but there were special units, trained as priests, whose job was to enforce temple law and protocol. These laws often had to do with not only protecting temples and tombs but with preventing blasphemy in the form of inappropriate behavior at festivals or improper observation of religious rites during services.

Organization & Duties

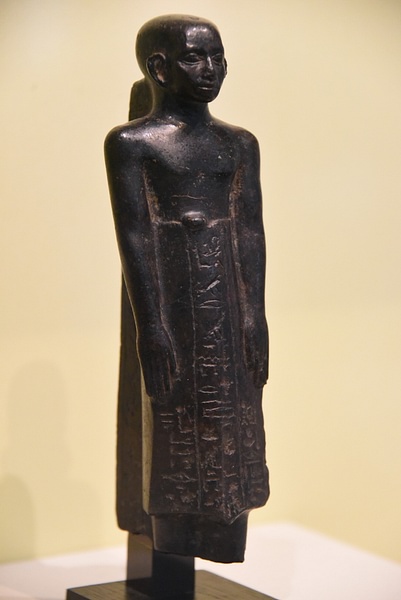

As head of state, the pharaoh was commander-in-chief of the military and also the police force but, in practice, his vizier was the top official of the judicial system. The vizier chose the judges and appointed the chief of police whose title, Chief of the Medjay, was a carry-over from the time when the police force was mainly comprised of Nubian warriors.

The Chief of the Medjay was always an Egyptian who employed other Egyptians as his deputies while Nubians continued to make up the units who served as the pharaoh's personal bodyguards, watched over markets and other public places, and protected the royal trade caravans. The chief also appointed what would amount to sub-chiefs of different municipalities who selected their own deputies and assigned constables to different beats.

Ultimately, a police precinct was responsible to the vizier, but practically they answered to their individual chiefs who then answered to the Chief of the Medjay. The exception to this rule were the temple police who were under the supervision of the head priest of a given temple. Even these men, however, were ultimately accountable to the vizier. There was no oath taken upon becoming a police officer; one was expected to recognize one's place in society, as dictated by the order established by ma'at, and perform one's duties accordingly.

There were different types of police units who were given specific responsibilities and duties. Temple priests, for example, not only guarded the temple but monitored – and modified – behavior of participants at festivals and religious services. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson elaborates:

The temple police units were normally composed of priests who were charged with maintaining the sanctity of the temple complexes. The regulations concerning sex, behavior, and attitude during and before all religious ceremonies demanded a certain vigilance and the temples kept their own people available to insure order and a harmonious spirit. (207)

Other police units were assigned duty guarding caravans, protecting border crossings, watching over the royal necropolises, supervising the transport and the daily labor of slaves (especially in the mines), and safeguarding important administrative buildings in urban centers. The Molossian became the preferred police dog at this time and was used especially for guarding tombs and public places. Rural communities usually took care of their own judicial problems through appeal to a village elder, but even many of these had some sort of constable who enforced the laws of the state.

Among the most common crimes, especially toward the latter part of the New Kingdom, was tomb robbing and court documents from this time (c. 1100 - c. 1069 BCE) make clear that this problem was of almost epidemic proportions. As the New Kingdom was slowly collapsing, the bureaucracy which enabled state payment of workers, judges, police, and everyone else crumbled with it.

The best-known example of this is the difficulties of the government in paying the tomb workers of the village of Deir el-Medina in c. 1157 BCE which resulted in the first known labor strike in history. While some of these workers decided to simply lay down their tools and protest their ill treatment, others took matters into their own hands and developed the habit of robbing tombs.

The Police & Tomb Robbing

It was difficult to catch a tomb robber in the act and, if caught, to prosecute successfully for the very same reason that people were robbing tombs: the decline of the power of the central government meant that each person had to do what they could to survive as best as possible – and this included policemen, legal scribes, and judges. There are many documents which establish that people caught robbing tombs were interrogated, judged, and punished but there are others which make clear that one could buy one's freedom with the very loot one had stolen by paying off an authority figure.

The level of corruption toward the end of the New Kingdom affected every social class and occupation in the land. In one case, a tomb worker, priest, and the watchman responsible for safeguarding the necropolis were all indicted in a robbery and the priest's son was called as a witness to the crime as well as a suspect:

The priest, Nesuamon, son of Paybek, was brought in because of his father. He was examined by beating with the rod. They said to him: "Tell the manner of thy father's going with the men who were with him." He said: "My father was truly there. I was only a little child and I know not how he did it." On being further examined, he said: "I saw the workman, Ehatinofer, while he was in the place where the tomb is, with the watchman, Nofer, son of Merwer, and the artisan ___, in all, three men. They are the ones I saw distinctly. Indeed, gold was taken and they are the ones whom I know." On being further examined with a rod, he said, "These three men are the ones I saw distinctly." (Lewis, 260)

Nesuamon's claim that he was "only a little child" should not be interpreted to mean he was young in years; he was only claiming that he was innocent of participating in the theft and knew nothing of how it was carried out. Court documents regularly specify use of the bastinade to beat prisoners on the palms of their hands and soles of their feet in order to exact a confession. As a suspect, Nesuamon is 'examined' through these beatings, but witnesses who were considered unreliable could expect similar treatment. In this case, the fate of the father and the three men, as well as Nesuamon, is unknown but, if found guilty, they could have faced punishment ranging from flogging to amputation of the nose or hand and even the death penalty.

In Egyptian state courts, guilt was assumed and innocence had to be proven beyond doubt. There are a number of instances in which the accused is beaten with the rod and maintains innocence, refusing to give a confession; in such cases, the person is set free. The stigma of being arrested followed the individual afterwards, however, and some records show people who were exonerated still being referred to years later as 'great criminal' which simply meant that they had once been accused of a crime.

Decline of the Police Force

In the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE) the police force was still operational but with little of the efficiency of the New Kingdom at its height. The Third Intermediate Period's records are sparse when compared to earlier eras of Egypt's history because with the government divided between Tanis and Thebes in the early years – and numerous civil wars later – there did not exist the kind of stability and bureaucracy of the periods known as 'kingdoms'.

The police force and judicial system were still operating but exactly how closely they were aligned with the earlier understanding of ma'at is dubious. There is ample evidence that court scribes, judges, and police could be bought. During the 21st Dynasty, founded by the nomarch Smendes (c. 1077-1051 BCE), police corruption by way of taking bribes to look the other way and even extortion of citizens by police officers appears common practice. The famous Papyrus of Any (known today as Papyrus Boulaq IV), dating from around this era, offers the following advice:

Befriend the herald (policeman) of your quarter,

Do not make him angry with you.

Give him food from your house,

Do not slight his requests;

Say to him: "Welcome, welcome here."

No blame accrues to him who does it. (Dollinger, 2)

Although the passage has been interpreted to simply mean one should be friendly with the local constable, the last line – "no blame accrues to him who does it" – has suggested to some scholars that the earlier advice of not making the policeman angry, giving him food, agreeing to his requests, and allowing him into one's home point to the possibility that citizens at this time were paying protection money to local officers. As noted, a person accused of a crime was presumed guilty until proven innocent, and the testimony of a police officer was taken far more seriously than that of a citizen. It was therefore in one's best interest to be on good terms with the local police.

The interpretation of the Any passage as referring to widespread corruption is probably sound in that the level of accountability police officers were held to during the New Kingdom did not exist for the most part in the Third Intermediate Period. The corruption of the judicial system – from the judges to the scribes to the police – is well established during the decline of the New Kingdom and continued into the following eras.

Under the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) the police force was reformed and operated at a much higher level of integrity but, again, would never reach the heights it had known in the early years of the New Kingdom. The traditional understanding of the concept of ma'at had been undermined by what many people recognized as a betrayal of the most sacred value of the culture by those who were expected to protect and uphold it. The labor strike of c. 1157 BCE by the tomb workers of Deir el-Medina was a completely unprecedented event in Egyptian history and pointed to the failure of the government, especially the pharaoh, to maintain ma'at in caring for the people. However ma'at was understood following the New Kingdom, it never seems to have carried the same cultural weight it once did.

The early Ptolemaic pharaohs certainly did their best to revive ma'at and bring back the grandeur of Egypt's past but this initiative was not a priority for successive kings. A police force still existed under the Ptolemies but this dynasty had armies to protect caravans, man border garrisons, and serve as bodyguards and the police force was no longer considered as important as it once had been. When Egypt was annexed by Rome and occupied, Roman soldiers were stationed throughout the country and the Egyptian police force became irrelevant and disappears from the historical record.