This visit filled me with great pride. I was about to explore the history of my home region. The things that were happening ages ago to the place that my ancestors called home. My home city, on the banks of the Strymon river, is a very ancient settlement, dating back to the 1400's BCE, but it only became an important town, even reaching the level of provincial capital, during the Byzantine era, especially during and after the reign of the Macedonian dynasty. My home city is Serres, ancient Siris, and before the Byzantine period it was playing second fiddle to the other famous ancient city in the area: Amphipolis.

Following the stream of the river Strymon to the south, just before it reaches the northern Aegean Sea, lies the town of Amphipolis. Now a small village, it was a thriving Metropolis during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, while becoming an important town for early Christianity, much like the city of Philippi, to the northeast. Being right on the Via Egnatia, like Philippi, it became a cultural and economic centre of the Mediterranean world. Its history starts much earlier than this, though, when as an ancient Athenian colony, it was the cause of much controversy during the Peloponnesian war that ravaged ancient Greece in the late 5th century BCE. Its history also crosses with the history of the rise of the Macedonian Kingdom and its subsequent spread of Hellenism in the eastern Mediterranean, with the campaigns of Alexander the Great.

Upon arriving close to the town, the first piece of history that awaits the visitor is one from the Byzantine era. The Byzantines built the north tower in 1367 CE which stands on the right-hand side of the road that leads upwards to the modern village, the museum and ancient ruins. The tower, along with its twin one on the other bank of the river, provided protection, among others, for the Athos peninsula and its monastic community. At this point, I wasn't sure that I was going the right way, so I hesitated to keep going uphill since I had already seen a sign that pointed to the bridge of Amphipolis. So, I headed back and went to see the bridge. I should mention here that I am Bridge Engineer, so this would be a unique experience for me.

Ancient Bridge of Amphipolis

The ancient wooden bridge of Amphipolis was discovered in 1977 CE and is a unique find for Greek antiquity and a rare one for the wider ancient world. It was built to connect the city of Amphipolis with its port, crossing the river Strymon. The remains of the bridge include several petrified timber piles that supported the bridge's south abutment. Parts of the south abutment also survive, made of stone masonry and marble blocks that also form part of the north-west wall of the city. The bridge lies in front of Gate C of the city walls. The remains of the bridge cover an area of 13 m in width, and the diameter of the piles vary between 70 mm and 290 mm, most of which have a circular section while some have a square section. Their heights are between 1.5 m and 2.0 m. There are also several horizontal beams with the longest surviving one measuring 4.5 m which were used to support the bridge's timber deck. The lower ends of the piles were cut into shaped edges, which in some cases were placed in iron-pointed heads. Archaeologists discovered many such iron heads along with fragments of dowels, clamps and tools by the river bank.

The excavation is distinguished by two groups of piles:

1. Piles with large dimensions placed at deep levels.

2. Piles set higher with smaller diameters.

The lower piles give a better picture of the original pattern. Most of them are placed in small groups of three or four to strengthen the foundation of the bridge. They form 12 non-parallel rows, measuring 6 m in width. The total length of the bridge structure was around 275 m.

With regards to the age of the bridge, the first historical reference of its existence dates back to 422 BCE. However, carbon dating techniques put the first construction of the bridge at around 600-550 BCE.

The first historical reference to the bridge is in the works of Thucydides, the Athenian historian and military commander who wrote about and fought in the Peloponnesian War. The bridge played a significant role in the battle of Amphipolis, in 422 BCE, between Spartan and Athenian forces for the control of Amphipolis and the nearby Pangaeon Mountain's gold and silver mines as well as the ship-making timber supply from the oak forests that surrounded (and still do) the Strymon river valley.

Amphipolis was initially captured and renamed (from its previous name Ennea Odoi meaning Nine Roads) by the Athenians, almost 40 years before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian war in 431 BCE, and introduced to the Delian League. During the few years preceding the war, the residents of Amphipolis were frustrated by their Athenian treatment and sought independence. Thus, when the Spartan general Brasidas arrived in the city in 424 BCE, he was greeted as a liberator, and the residents of Amphipolis, Siris and their nearby towns became allies with the Spartans.

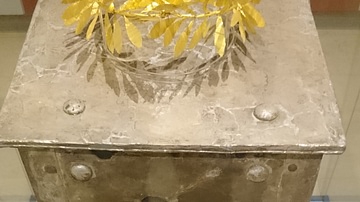

The Athenians would not simply let their former allied city fall into enemy hands, so they tried to recapture it, an attempt that led to the Battle of Amphipolis in 422 BCE. The Spartans took advantage of the geography of the area with the help of the locals and used the bridge to narrow down the Athenian forces. These tactics are similar to the famous Battle of Thermopylae (480 BCE), or even more analogous to the Battle of Stirling Bridge (first war of Scottish independence, 1297 CE). The Spartans won the battle with the help of the residents of Amphipolis and other towns of the Strymon valley. Despite his win, Brasidas was wounded in the battle and died a few days later. The Amphipolitans buried him as a hero in the nearby necropolis. Archaeological excavations discovered his silver ossuary which is now on display in the Archaeological Museum of Amphipolis.

The bridge appears later in history multiple times. It was crossed by Alexander the Great on the commencement of his historic campaign, in 334 BCE, after he possibly assembled his army and navy near the harbour of Amphipolis. There are accounts of systematic repair and maintenance works on the bridge during the Roman era, the Byzantine era and as late as the mid-Ottoman period in around 1620 CE, when the last historical trace of the bridge appears. The Byzantine extension of the bridge along with a dam built in the same period was destroyed in 1929-1932 CE when major works were done to shift the Strymon's riverbed.

Museum of Amphipolis

Onwards to the Museum of Amphipolis, I was surprised to see that it is an imposing building, well organised to display the antiquities, and welcoming to the visitors. Chronologically ordered, the artefacts take you on a long trip through history describing the first settlements of the Strymon valley, the thriving Athenian colony, the Peloponnesian War, the Romans, the Early Christians and so on. One of the most impressive sets of exhibits was the children's toys. A very close look at the everyday life of ancient Amphipolitans, the raising of their children and the effort they made for their families. Of course, the silver ossuary of the Spartan general Brasidas is probably the highlight of the museum.

Archaeological Sites

After leaving the museum, I headed further uphill to the remains of the actual city. The early Christian elements dominate the area as the remains of the basilicas, the Christian mosaics and Christian inscriptions are all over the place. But the visitor can also see the gymnasium and the remains of a mansion that may have been the one of the city's governors, the Christian bishop, or both, during the ages.

Leaving Amphipolis, I headed towards where I knew that another ancient town is being excavated at the moment; the settlement of Argilos. Unfortunately, I did not take a perfect look at it because the archaeological works are ongoing, but I did manage to take a few photographs.

Argilos

According to Ptolemy, the name of Argilos is of Thracian origin, even though the town was a colony of settlers from the Cycladic island of Andros. The legend says that the Andrian settlers saw a subterranean animal, possibly a mole, that was sacred to the Sun-god Apollo and, therefore, named the city after the clay ground (“argilos” means “clay” in Greek). This notion is supported by the coins found in the region which have a mole represented on them. The Andrian origin of the town is attested by the works of Thucydides, who also adds that the town was part of a larger colonial operation from Andros (655-654 BCE), including several other towns around the Gulf of Strymon, like Aristotle's hometown, Stagira. As a natural port, the town served as a trading centre of the northern Aegean.

From Athenaeus' work, “Deipnosophist”, we learn about the local crops, being cereals, vineyards and several fruit trees. They were also very skilled animal breeders and supplied the area as well as the whole of the Aegean with meat. Herodotus also mentions the town while describing the march of Xerxes south of the Pangaion mountain, where he made a brief stop in Argilos. The town of Argilos was the major port city of the region before the rise of Amphipolis and its satellite port town of Eion. Strabo also mentions the town, so it was still active during Roman times, even if it had already declined, and this is the last time the town is mentioned in historical and geographical accounts.

Lion of Amphipolis

Almost half way between Amphipolis and Argilos stands the most iconic monument of the ancient region of Serres and the Strymon Valley; the locally famous Lion of Amphipolis. It dates back to the days of Alexander the Great, and it's a monument to one of his generals, Laomedon of Mytilene. This Lion stands as a symbol for regional communities, being something like a coat-of-arms for the people. Even the city's football team use it as their symbol. It is a symbol of what it means to be a citizen of Serres.

I am acutely aware that anyone who may be reading this article, may expect to see a bit about the recently discovered tomb. Unfortunately, the site is so inaccessible, that there isn't an actual road to lead there. You'll need to go off road for a while to reach the place and still won't be allowed to see the findings. So even though I would love to mumble about the tomb, speculate about who it may have laid on its inside, it was not part of my visit, so I cannot digress too much.

This visit was the last ancient expedition that I undertook during that visit in Greece and I returned home full of images, motivation to read further, and a little bit of healthy national pride! I was also frustrated to see that there are so many beauties both natural and historical that the country should have been littered with tourist destinations (more than it already is). A foreign visitor cannot easily locate and access these places, so proper advertisement, and promotion is urgently required. None of the places I visited was more than an hour's drive from a pristine beach, a green forest or a mountain (in the case of Amphipolis the sea is ten minutes away) so tourism should have been thriving. It is a matter that I hope I can see resolved in the future, or, at least, considered.