Diodorus Siculus, the 1st century BCE historian, took great pride in precision of description but, even so, could not refrain from adding his own personal views and interpretations of historical events and persons. In the following passage, Diodorus describes the reign of King Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BCE) with a focus on the role `fortune' or `fate' played in the king's successes.

In ancient Greece, the Three Fates (Clotho, Lacheses and Atropos) who spun, measured and cut the thread of a human life were considered an implacable force (it is written that not even Zeus, the king of the gods, could change their course). In time, however, certain writers and thinkers (Plato, among them) came to object to the concept of man's fate in the hands of otherworldy beings over whom the individual had absolutely no influence. Diodorus, as a Greek writer, carefully shapes the following account to refute the notion that the Fates had anything to do with Philip's career but, of course, cannot avoid the fact of Philip's death by assassination in 336 BCE and this he does, as was customary, attribute to Fate. The passage is among the first to credit the reign of Philip with enabling his son, Alexander, to become `The Great':

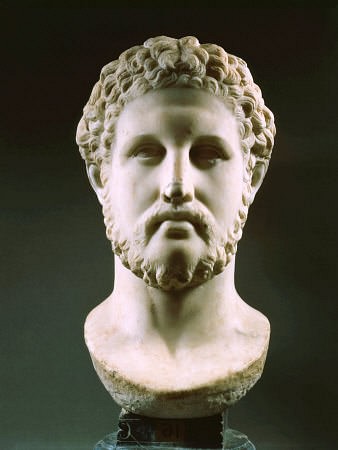

During the twenty-four years of his reign as King of Macedonia, in which he started with the slenderest resources, Philip built his own kingdom up into the greatest power in Europe. Having found Macedonia under the yoke of the Illyrians, he made her mistress of many great nations and states; and, by force of personal chracter, he estabished ascendancy over the entire Hellenic world, whose component states offered him their voluntary submission. He subdued the criminals who had plundered the shrine at Delphi, and was recompensed for his championship of the Oracle by being admitted to the Council of the Amphictyons, in which he was assigned the votes of the conquered Phocians as a reward for his zeal on behalf of Religion.

After subduing the Illyrians, Paeonians, Thracians, Nomads and all the surrounding nations, he projected the overthrow of the Persian Empire, landed forces in Asia and was in the act of liberating the Hellenic communities when he was interrupted by Fate – in spite of which, he bequesthed a military establishment of such size and quality that his son Alexander was enabled to overthrow the Persian Empire without requiring the assistance of allies. These achievements were not the work of Fortune but of his own force of character, for this king stands out above all others for his military acumen, personal courage and intellectual brilliance.

Following the dazzling success of Alexander the Great's conquests (in Alexandria, Egypt, he declared himself a god and, after the Battle of Gaugamela, many believed he really was) it became customary among ancient writers to downplay contributing factors and either deify Alexander for his many accomplishments or villify him but, either way, to always focus solely on Alexander himself. Although other writers would follow suit, Diodorus was among the first to recognize that Alexander had been given a great advantage by his father and that Philip's successful reign had everything to do with his own character and intelligence and much less to do with the arbitrary chances of fate.