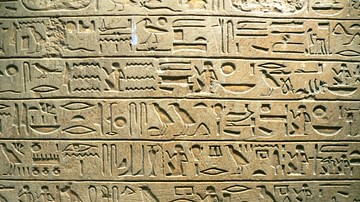

Egyptian law was based on the central cultural value of ma'at (harmony and balance) which was the foundation for the entire civilization. Ma'at was established at the beginning of time by the gods when the earth and universe were formed. According to one version of the story, the god Atum emerged from the swirling waters of chaos to stand on the first dry land, the primordial ben-ben, to begin the act of creation. The force of magic (heka) was with him, personified in the god of magic Heka, and it was this force which gave power to ma'at, the principle which was later personified as the goddess of the same name. Ma'at allowed the universe and life on earth to function as it should – in balance – and heka was the power which sustained ma'at. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson writes:

For the Egyptians, heka or 'magic' was a divine force which existed in the universe like 'power' or 'strength' and which could be personified in the form of the god Heka...his name is thus explained as 'the first work.' (110)

Heka's first "creation" was ma'at, and so the concept of balance and harmony as an essential aspect of life became the most deeply held conviction of Egyptian society from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) onwards. Although the personification of Ma'at as a goddess does not appear until the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE), the value she represented – as well as the magic which sustained that balance - seems evident in architecture and carvings of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE), establishing this value as the core foundation for the society which then developed.

Early Development of Law

If people had been able to recognize the benefits of living their lives in accordance with ma'at, there would have been no need for laws, but since selfish desires frequently override common sense, people acting in their own self-interest – and at the expense of others – needed to be punished and examples and precedent set for others who might be tempted to do the same.

Although some form of a law code seems to have existed, archaeologists have not uncovered any document similar to a codified set such as the Code of Ur-Nammu or that of Hammurabi of Babylon. The Egyptian literary work known as The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, from the Middle Kingdom (2040 - c. 1782 BCE), establishes that a law code and an administrative judicial system had been in place long before this time. Some rudimentary law code existed during the Predynastic Period (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) but an actual legal system had to have been in place by the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) because it was already in use in the early years of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE).

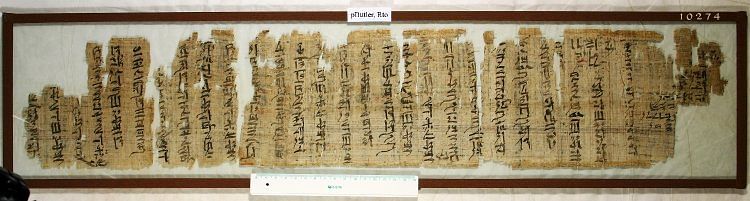

The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant also establishes that justice and fair treatment for all – no matter one's social class, age, or gender – were highly prized concepts for the Egyptians. It is clear from works such as The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, from notes, letters, judgments, and revisions concerning the law made by later kings that judges and magistrates were working from a standard set of laws but the specifics of such a document are unknown.

It is also clear, however, that the law was based on ma'at and operated from a principle of precedent: a judgment on a particular crime in the past would establish the basis for future sentences. What made a judgment legal and binding, however, was not necessarily the skill or wisdom of a judge or magistrate but how closely a legal decision aligned with ma'at.

Importance of Ma'at

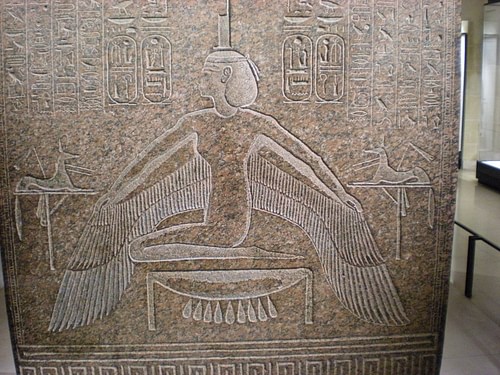

The principal responsibility of the king was to uphold ma'at; once this was understood as a ruler's primary role, all other responsibilities of the throne would fall into place. A central observance of a king's inauguration ceremony, in fact, was his offering the spirit of ma'at – personified in a statue – to the other gods as a promise he would maintain universal balance.

In time, the concept came to be personified as a goddess with a white ostrich feather who became so important to the culture that she appeared with the gods Osiris, Thoth, and Anubis in the Hall of Truth after a person's death where the heart of the deceased was weighed against her white feather of truth. If the heart was found lighter than the feather, the person was allowed to go on to eternal life in the Field of Reeds; if the heart was heavier, it was dropped to the floor where it was eaten by the monster Amut and the soul of the person ceased to exist.

One's heart would be lighter if one had lived in accordance with ma'at. Ma'at was the spirit of all creation in harmony and, if a person was in accord with that spirit, they lived well on earth and also had good reason to hope for eternal peace in the afterlife; if one refused to live in accordance with the principle of ma'at, then one suffered the consequences – in life and after death - which one would have brought upon one's self.

If a person decided to break the law by stealing grain from another, the thief had not just deprived someone of their property but had disrupted the balance which allowed the world to function as it should. Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson comments on this, writing:

Ma'at was the model for human behavior, in conformity with the will of the gods, the universal order evident in the heavens, cosmic balance upon the earth, the mirror of celestial beauty. Awareness of the cosmic order was evident early in Egypt; priest-astronomers charted the heavens and noted that the earth responded to the orbits of the stars and planets. The priests taught that mankind was commanded to reflect divine harmony by assuming a spirit of quietude, reasonable behavior, cooperation, and a recognition of the eternal qualities of existence, as demonstrated by the earth and the sky. All Egyptians anticipated becoming part of the cosmos when they died, thus the responsibility for acting in accordance with its laws was reasonable. Strict adherence to ma'at allowed the Egyptians to feel secure with the world and with the divine plan for all creation. (152)

No one could feel secure, however, if ma'at were ignored and people were allowed to behave in any way they pleased. The laws of Egypt were created – and a judicial system set in place – to ensure there were immediate and unpleasant consequences for upsetting the balance of society. These laws applied to everyone from the peasant to the king because it was understood that everyone in society had a part to play and a role assigned them by the gods; if a magistrate or judge or vizier should play favorites or judge unfairly, they would be just as guilty of disrupting ma'at as a thief, robber, or murderer.

Balance & the Law

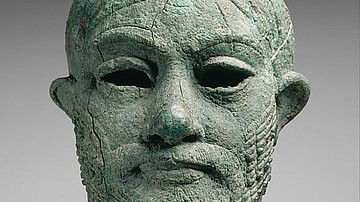

To ensure that justice was provided for everyone in the country – regardless of social class – only the best men were chosen for positions of legal authority. The vizier of the land had to meet stringent requirements for the position, and these included moral and ethical aspects as well as administrative and intellectual. The position of the Egyptian vizier in the present day is usually understood as comparable to "king's counselor" but he was actually the moral compass and chief administrator of the entire country.

A famous vizier of the New Kingdom of Egypt, Rekhmira (also given as Rekhmire), served under the pharaohs Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) and his son Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE). He is best known for the text Installation of the Vizier (also known as the Instruction of Rekhmira) which describes the duties of the office, how one is chosen for the position, and how a vizier should comport himself. The text emphasizes mercy and compassion but the overall focus is balance – harmony – in trying to better the lives of the unfortunate and relieve people's suffering:

I defended the husbandless widow. I established the son and heir on the seat of his father. I gave bread to the hungry, water to the thirsty, meat and ointment and clothes to him who has nothing. I relieved the old man, giving him my staff, and causing the old woman to say, "What a good action!" I hated inequity, and wrought it not, causing false men to be fastened head downwards. (van de Mieroop, 178)

Since the law was based on the divine principle of ma'at, it was considered perfect in origin and should not be misused for one's personal ends. A judge or any other legal authority who was found guilty of abusing his power faced punishments ranging from amputation of the hands to drowning. The law applied equally to everyone in Egypt and corruption was not tolerated even toward the end of the New Kingdom when corrupt practices from the top of Egypt's hierarchy to the bottom were rampant.

The Eloquent Peasant & Decline

The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant illustrates the Egyptian value of justice clearly. In the story, a peasant named Khun-Anup is beaten and robbed by Nemtynakht, a rich landowner, who tells him there is no use in complaining because no one in authority will value a peasant's word against that of a wealthy landsman. Khun-Anup refuses to believe this, however, and presents his case to the local magistrate.

The magistrate, Rensi, is moved by the peasant's case but finds his speech so eloquent that he reports the situation to the king, and the king, intrigued, directs Rensi to keep the peasant talking and record his speeches. Rensi does as he is instructed, refusing to address the complaint of Khun-Anup but providing him (as well as his family back home) with food and drink. Finally, after Khun-Anup has made nine petitions – all of which have been recorded by Rensi's scribes – he is rewarded with justice: all the lands belonging to Nemthnakht are given to him and, further, he is honored by the king who considers him a master of rhetoric.

The story was popular with audiences from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt through the New Kingdom, and probably later periods, but increasingly failed to reflect how justice was administered or how society was actually living the tale's ideals. Toward the end of the New Kingdom, balance was lost during the reign of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE), was never fully regained, and led to a number of significant problems.

The time of Ramesses III was the period of decline for the Egyptian Empire of the New Kingdom. The invasion of the Sea Peoples in 1178 BCE necessitated an enormous expenditure in defense, and even though Egypt was victorious, the effects of this event sent ripples through the governmental bureaucracy which maintained society. The immense loss of life from the invasion resulted in a depleted labor force, which meant fewer people to work the land and a poor harvest. This situation was worsened by weather conditions, and the regular distribution of grains and goods from the land, regularly handled by the efficient bureaucracy, broke down as resources became scarcer and officials more corrupt.

Although Ramesses III was a good king – considered the last effective pharaoh of the New Kingdom – he failed to maintain ma'at as the prime directive of his office. His insistence on maintaining the tradition of the pharaoh's 30-year jubilee celebration, in spite of the difficulties the country faced, caused significant resources to be directed to the court, and this decision meant that others, further down on the hierarchy, would have to do without.

Problems became apparent in c. 1159 BCE when payment to the tomb workers at Deir el-Medina was late and, in an unprecedented move, they went on strike. No workers had ever gone on strike before in Egypt; it was literally unthinkable. Everyone in the social structure had a place and a responsibility, and one could not simply decide one day to ignore that. When the workers struck, the officials were unable to handle it and, lacking any kind of experience with this sort of situation, tried to buy the workers off with pastries from the local temple.

The situation was finally resolved and the workers paid but the strike was the result of a problem no one knew how to address: a breach in the observance of ma'at by a reigning king. It was the king's responsibility to model behavior for his people but, in this case, the tomb workers were forced to remind the king of his obligations and his transgression. The strike itself was a disruption of balance which called attention to the greater transgression of the ruler.

By the time of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE), the empire had fallen and slowly drifted into the era known as the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE). Although a story like The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant may still have been popular during this time, it no longer reflected the practical administration of justice. Offices as high as that of the vizier down to the street level of police officers were corrupt and works like The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant or the Instruction of Rekhmira were no longer relevant because few people were living by those principles anymore. Once the value of ma'at was compromised, balance was lost, and the legal system founded on divine harmony began to decline.