The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant is a literary work from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) which illustrates the value society placed on the concept of justice and equality under the law. In the story, a peasant named Khun-Anup is beaten and robbed by Nemtynakht, a wealthy landowner, who then tells him there is no use in complaining to the authorities because no one will listen to a poor man. The rest of the tale relates how Khun-Anup, believing in the power of justice, refutes Nemtynakht and wins his case. According to Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim:

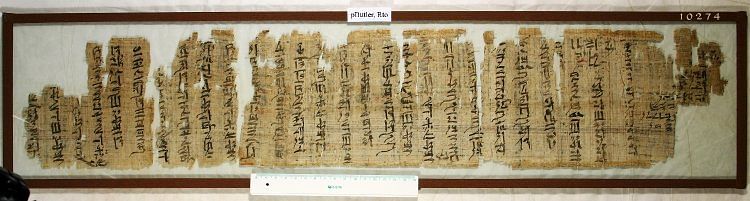

This long work is preserved in four papyrus copies, all dating from the Middle Kingdom. The individual copies are incomplete, but together they yield the full text, which comprises 430 lines. The three principal copies are P. Berlin 3023 (B1), and P. Berlin 3025 (B2), and P. Berlin 10499 (R); the fourth is P. Butler 527 = P. British Museum 10274. (169)

The copies made of the story – and there were probably many more - attest to its popularity; it was enjoyed from the Middle Kingdom onwards because, as Egyptologist Margaret Bunson notes, "such tales delighted the Egyptians, who appreciated didactic texts and especially admired the independence and courage of the commoners" (85). While this may be true, the presentation of the story – the form the author chose to work in – would also have contributed to its popularity.

The work takes the form of a short story complete with dialogue but the speeches of Khun-Anup are given in poetry in order to provide an audience with both verisimilitude (one is hearing the eloquence of Khun-Anup first hand) and variation in form (the work is both prose and poetry) which breaks the point of view between a straight third-person narrative and the first-person petitions of the peasant. While this may seem to be the same as an author's use of dialogue in a short story, the significant difference is in the form of the poetic passages and the identity of the speaker: an uneducated peasant was not thought capable of mastering rhetoric.

Summary

The story begins with Khun-Anup leaving his wife and children at home to travel south to market with his goods. A detailed list is given of everything he is carrying, and the author makes clear it is all quite valuable. On his journey, he must pass through the property of the landowner Nemtynakht – one of the upper class – who sees Khun-Anup's goods and decides to steal them.

Nemtynakht understands that he cannot just take the goods without a reason and so devises a trap. The peasant will have to lead his donkeys through a narrow path on the land which is bordered on one side by Nemtynakht's barley and on the other by water. Nemtynakht has a piece of cloth laid on the path, the ends of which touch the water on one side and the barley on the other, and tells Khun-Anup he cannot walk on it. When the peasant tries to avoid it by moving toward the barley, one of his donkeys eats some of it and the landowner has his justification.

He beats Khun-Anup for allowing his donkey to steal an ear of barley and then confiscates all his other donkeys and his goods. Khun-Anup cries out for justice, but Nemtynakht tells him to be quiet; no one will listen to the complaint of a peasant against a landowner. Khun-Anup, however, is not going to settle for this kind of injustice and goes to town to find the magistrate Rensi, the son of Meru, who presides over the region.

As the title of the piece suggests, this peasant is particularly skilled in public speaking and convinces Rensi that he has suffered a great wrong. Rensi agrees to take the case to other magistrates to get their opinion. The other judges, however, consider it simply a matter of a peasant at odds with a landowner and dismiss the case.

Rensi then appeals to the king, telling him how eloquent the peasant is, and the king instructs him to feed the peasant - as well as send food to his wife and children – but to deny his appeal in order to keep him making his speeches. These speeches, the king instructs, should be written down and brought to him and then the peasant will receive justice.

Rensi does as his king commands and forces Khun-Anup to petition for justice nine times; each time his words are written down. In the end, the king rewards Khun-Anup for his eloquence and persistence in seeking justice. The landowner's property is confiscated and given to the peasant.

The Speeches of Khun-Anup & Ma'at

Although certainly eloquent, the speeches Khun-Anup gives are nothing new; they are often common phrases from earlier in Egypt's history concerning law, justice, and the right way to live in accordance with ma'at. Ma'at (defined as 'harmony' and 'balance') was the central cultural value of the Egyptian civilization. The gods established ma'at at the creation of the world, and the human understanding of true justice was informed by this concept of living in balance.

It was not just Egyptian law which was based on ma'at, however, but every aspect of one's life. Living in accordance with ma'at meant being considerate of others, mindful of one's place in the social hierarchy, performing the proper rites concerning veneration of the gods, and respect for one's ancestor, observing the correct mortuary rituals and providing offerings for deceased loved ones, and honoring nature through care for the environment and wildlife. The primary responsibility of the king himself, in fact, was the maintenance of ma'at. If one lived in tune with the spirit of ma'at, one was assured of not only a harmonious existence on earth but entry to paradise in the next world.

The concept of ma'at was so important that it was personified as a goddess who appeared along with Osiris, Thoth, and Anubis in the Hall of Truth at the judgment of the soul after death. The white feather of the goddess Ma'at was placed in the balances opposite the heart of the soul of the deceased; if the heart was lighter than the feather, the soul could proceed to paradise and, if heavier, it was dropped to the floor where it was eaten by the monster Amut and the soul ceased to exist. Non-existence was more terrifying to the ancient Egyptians than any kind of 'hell', and so this was a powerful incentive for one to live one's life in accordance with ma'at.

These speeches of Khun-Anup's were maxims on not only how one should live but also the responsibility of judges to be fair and uphold the law no matter the social class of plaintiff or defendant. Egyptologist William Kelly Simpson, writing on The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, notes:

The appeal of the text is not so much in its actual content as in the artistic manner in which that content is expressed, for it says nothing new or significant on its subject. The subject of the peasant's speeches is the Egyptian concept of Ma'at. (25)

Each of the speeches repeats and develops what Khun-Anup has already said with slightly different emphasis on various points, but his central focus is on the duty of those in authority to dispense justice equally under the law. A good magistrate is one who does not discriminate because of a plaintiff's class but who recognizes the divine benefits of living in balance and maintains justice for all the people. In the peasant's third petition he addresses Rensi, saying:

High steward, my lord,

You are Ra, lord of sky, with your courtiers,

Men's sustenance is from you as from the flood

You are Hapy [god of the Nile] who makes green the fields

Revives the wastelands.

Punish the robber, save the sufferer,

Be not a flood against the pleader!

Heed eternity's coming,

Desire to last, as is said:

Doing justice is breath for the nose.

Punish him who should be punished,

And none will equal your rectitude.(lines 140-147, Lichtheim, 175)

Later, after Rensi has ignored his requests repeatedly, Khun-Anup's petition becomes more pointed. He directs his criticism at Rensi personally as a magistrate who is at odds with ma'at, who, through his unjust actions, devalues his office and harms not only himself but everyone else:

You are learned, skilled, accomplished,

But not in order to plunder!

You should be the model for all men,

But your affairs are crooked!

The standard for all men cheats the land!

The vintner of evil waters his plot with crimes,

Until his plot sprouts falsehood,

His estate flows with crimes!(lines 261-266, Lichtheim, 179)

Khun-Anup's speeches are reminiscent of earlier works from the genre known as Wisdom Literature and, especially, The Maxims of Ptahhotep which is dated to the earlier period of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE). At one point, the speaker in Ptahhotep says:

If a noble action is done by one who is in authority,

He will be of good reputation forever,

And all his wisdom will be for everlasting.

The learned man takes care for his soul

By assuring that it will be content with him on earth.

The learned man can be recognized by what he has learned

And the nobleman by his good actions;

His heart controls his tongue,

And precise are his lips when he speaks.

His eyes see and his ears are pleased through the hearing of the repute of his son

Who acts in accordance with Ma'at and who is free from falsehood.(lines 15:13-16;1, Simpson, 145)

The Maxims of Ptahhotep, like The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, emphasizes the importance of justice and equity in one's personal and professional life. Both pieces illustrate how the Egyptian understanding of law and proper conduct derived from the religious foundation of ma'at. The gods had established the simplest and easiest universal law to follow – harmony – and all one had to do to enjoy a full life was follow it and, for those in positions of authority, encourage and uphold it. In the case of The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, however, there seems a significant discrepancy between the supposed moral of the story and the action of the piece.

The Justice Contradiction

The cultural understanding of class distinction informs the entire story of the wronged peasant. Nemtynakht feels confident in robbing and beating Khun-Anup because, as he says, no one will pay any attention to him if he complains. The magistrate Rensi, who first hears the case, brings it to the other magistrates who dismiss it, just as Nemtynakht predicted, as a peasant trying to stir up trouble needlessly with a landowner. When Rensi brings the matter to the king, telling him of the peasant's eloquence, he is told to deny Khun-Anup the justice he seeks in order to encourage him to keep making his petitions; this command would seem to be at odds with ma'at.

Although the story is routinely identified by scholars as a didactic work on the value of justice in ancient Egypt – which it certainly is – this one element of the piece is often overlooked: how the king denies the peasant justice, and prevents Rensi from performing his sworn service, in order to have the peasant's petitions written down for his own use. It could be argued that the king instructs Rensi this way as a kind of test for Khun-Anup, to see if he is serious about pressing charges against the landowner, but the text itself does not support this interpretation. The king specifically tells Rensi:

As truly as you wish to see me in health, you shall detain him here, without answering whatever he says. In order to keep him talking, be silent. Then have it brought to us in writing that we may hear it. (lines 78-81, Lichtheim, 172-173)

At the end of the story, after the scribes have recorded Khun-Anup's petitions, they are presented to the king and "they pleased his majesty's heart more than anything in the whole land" (lines 132-133, Lichtheim, 182). It is only after the king is given the speeches that he instructs Rensi to perform his duty and give the peasant justice whereby Khun-Anup is given all of Nemtynakht's land and possessions. Lichtheim comments on the work, writing:

The tension between the studied silence of the magistrate and the increasingly despairing speeches of the peasant is the operative principle that moves the action forward. And the mixture of seriousness and irony, the intertwining of a plea for justice with a demonstration of the value of rhetoric, is the very essence of the work. (169)

However true that may be, it does not address the problem of reconciling a literary work which focuses on the importance of justice with the central plot device of that work which denies justice to the main character. The author could be implying that divine justice can never be perfectly administered through imperfect mortal magistrates, but this is not supported by the text; no censure is attached to the king's actions nor to Rensi's.

Conclusion

The most probable resolution to the problem lies in the universal nature of the concept of ma'at: the balance and harmony of law was not only for the one or the few but for all. The dynamic of the story relies on the eloquence and righteousness of the peasant as contrasted with the criminal act of the landowner and the seemingly selfish decision of the king to deny justice until he has gotten what he wants out of the situation. The author does not explicitly criticize the king because the speeches of the peasant will, presumably, be used to instruct others in proper behavior, and so the monarch is acting in a good cause.

Although it may seem a contradiction, the decision of the king would be in keeping with ma'at in that it would lead to greater harmony for a greater number of people. Khun-Anup is outwardly ignored by Rensi, but the king has commanded that the magistrate provide the peasant with food and drink – as well as his family back home – while his scribes record Khun-Anup's speeches. The king does provide the peasant with justice right away in providing for him – Khun-Anup is simply unaware of it – and also shows he has every intention of dispensing justice regarding the theft – as does Rensi – but needs to delay that decision to the one for the greater good of the many.

The alternation between prose and poetry throughout the piece builds the tension as Khun-Anup becomes increasingly frustrated until, finally, the piece ends in prose and the speeches stand out in greater highlight as maxims for leading the best life possible. An ancient audience would have recognized that, were it not for the king's decision, they would not have the benefit of Khun-Anup's eloquent defense of justice, and so the king would have been performing his duty after all in upholding and maintaining ma'at. In the end of the story, the peasant and everyone else gets what they deserve, what was wrong is righted, and balance is restored; all of which were the goal of justice in ancient Egypt.