The art of the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) of ancient China is characterised by a new desire to represent everyday life and the stories from history and mythology familiar to all. The arts were fuelled both by a political stability with its consequent economic prosperity and the development and highly successful combination of brushes, ink, and paper. Calligraphy, painting, lacquerware production, and jade carving were just some of the areas Han artists pushed forward the boundaries of what was possible to make technically and what was desired aesthetically by the ever-increasing number of art connoisseurs.

The Han Contribution

The art historian Mary Tregear gives the following summary of how art evolved under the Han:

Whereas in previous ages art had been associated with rituals and ceremonies, gradually evolving into a decorative expression of social status, the art first of the Qin and then of the Han is concerned with myths and everyday life. It was from the outset both a narrative and an expressive art. (50)

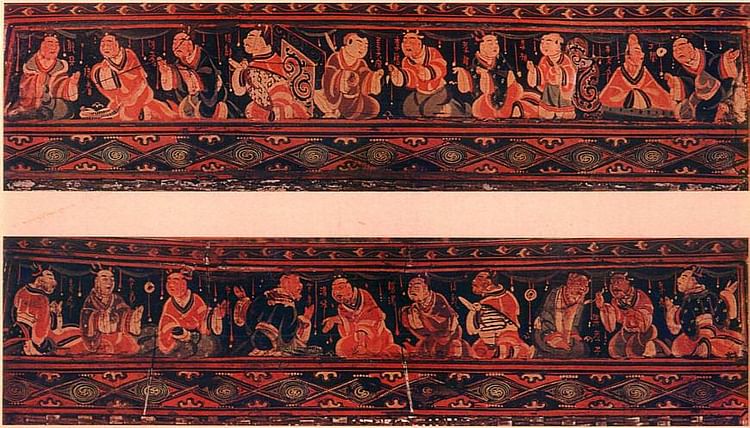

The Han, like the brief Qin dynasty before them, had acquired a vast swathe of Asia which encompassed many varied cultures, belief systems, and myths. Han rulers realised that art could be a useful tool in collecting this heritage together and presenting a unified and comprehensibly “Chinese” view of the world. People and daily-life, especially hunting, farming, fishing, and landscape scenes, became very popular. Decorative motifs abounded and became highly stylised in border decorations whose uniformity suggests the use of pattern books in the larger urban workshops. These motifs are especially prominent on pottery, lacquerware, and bronze mirrors.

Calligraphy

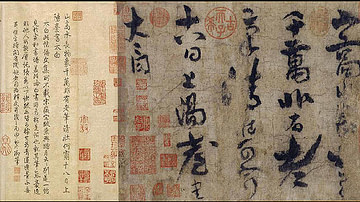

Developments in paper and the use of brushes and inks led to a boom in writing, which in turn created a need for illustrations of those texts. Indeed, these two art forms: painting and calligraphy would remain the two most important forms of artistic expression in China for the next two millennia. Engraved calligraphy was already well developed, and styles had evolved on surfaces such as bronze, stone, and bone, but the fluidity of paper and brush would lead to many more new styles of writing over the following centuries.

Using animal hair brushes and ink which was a mix of compressed pine carbon and thinned glue, calligraphers were now only limited by their imagination. Some writing styles produced flamboyant characters, others were heavy, some mixed heavy and light strokes, while still others were designed for speed. The composition of the characters together on the page was also an important consideration. Eventually, a whole connoisseurship developed amongst the Chinese literati, and excellent writing skills became essential for anyone wishing to be taken seriously by their peers.

Paintings

Silk had long been used as a medium for painting, but the increase in paper use and the greater availability of books were certainly a factor in the increase in paintings. Another reason for paintings' popularity was the stability provided by the Han government and the consequent accumulation of wealth by its more fortunate citizens. Wealthy individuals became both patrons and consumers of fine artworks. This demand led to innovations and experimentation in art, and one such area to benefit was figure painting.

Portraits became common, especially of filial sons but not only, with people of all kinds appearing on the stone walls, lintels and pillars of tombs, and on everyday objects like small boxes, and on coffins. One of the most celebrated examples of Han portraiture is from a basket discovered in the Lolang commandery in North Korea. The sides of the basket have panels with 7.5 cm (3 inches) high painted figures of famous historical personalities all of whom are labelled. Here, as elsewhere in Han painting, human figures are presented either in profile or three-quarter view.

Chinese painters began to portray narrative scenes in their work even before the more mature approach was brought to China by Buddhist monks from India along the Silk Road. This was especially seen in tomb wall paintings and on lacquer-painted wooden panels. Very often there are multiple scenes arranged either horizontally or vertically as they would have appeared if painted on a silk or paper scroll. An outstanding example is the c. 168 BCE portrayal of the various levels of human existence from the underworld to the heavens in the hanging discovered at the Mawangdui caves at Changsha.

Landscape painting would not come to the fore until the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 CE) but its beginnings were in the Han period and they probably stemmed from the popular depictions of the heavens. As with Chinese painting in general, the aim of the artist was not to copy exactly reality but always to represent the essence of a subject. For this reason, most scenes are painted from multiple perspectives, as opposed to the single viewpoint more common in Western art. Colour-shading was not used, even if Chinese artists were aware of it. Rather, the use of thinner and broader brush lines was the preferred method of providing depth to a painting.

Sculpture

Bricks were stamped and carved, as was stone, with relief scenes similar to those seen in paintings and are particularly common in tombs. This was a new departure for Chinese art, creating permanent artworks in durable materials. The finest examples are from the Wu Liang Shrine at Jiaxiang. Dating to 151 CE or 168 CE there are some 70 relief slabs which carry scenes of battles and famous historical figures, such as Confucius, all identified by accompanying texts and covering a chronological Chinese history in a pictorial record similar to a history book.

Large figure sculptures are rare from the Han period, but there are some statues representing generals and officials which were stood outside their tombs. Smaller-scale works include cast bronze sculptures of horses which are common in 2nd-century CE Han tombs. These are usually depicted in full gallop with only one hoof resting on the base so that they almost appear to be flying.

Painted earthenware figurines of single standing women, men, and servants are common. Cast bronze was used to make small figurines and ornate incense burners. These were often inlaid with gold and silver or gilded. One superb piece is a gilded bronze oil-lamp in the form of a kneeling servant girl, which dates to the late 2nd century BCE.

Jade was especially esteemed for its rarity, durability, purity, and certain mystical qualities. The material was carved into all manner of animals, people, and mythical creatures. Han Jade carvers now used circular cutting drills and iron tools, but pieces often have a lower quality finish than previously, which suggests they were starting to be made quicker and on a larger scale of production. Another feature of Han jade sculpture is the use of flaws and impurities in the jade to make them part of the sculpture. From the 1st century BCE, a pure white jade became available from central Asia following the expansion of the Han empire.

One unique but stunning art form was the creation of jade 'suits' to cover the body of the deceased in royal tombs. The 'suits' cover the contours of the body and are made from up to two thousand individually carved rectangular pieces of jade stitched together using gold or silver wire. Two outstanding examples come from the late 2nd century BCE tomb of Prince Liu Sheng and Princess Dou Wan at Mancheng. Reserved only for royalty, they nevertheless became so costly to produce that later rulers banned their use.

Minor Arts

Developments in techniques and kilns led to both higher firing temperatures and the first glazed pottery during the Han period. Pottery, especially the vessels painted with a grey slip commonly found in Han tombs, very often imitated the shape and decoration of bronze vessels. Low circular jars with lids and tall vases with a bulbous body and narrow base are characteristic. A painted dragon, phoenix, or tiger was a popular choice of decoration. Clay was also used to produce small unglazed models of ordinary houses which were set in tombs to accompany the dead and, presumably, symbolically meet their need for a new home. The two-storey models are useful indicators of now lost mud and wood structures; many are complete with adjacent animal pen and figurines of their occupants and animals.

Lacquer - a liquid of shellac and resin - was used to coat objects of wood and other material since the Neolithic period in China but, as with many other art forms, production took off under the Han. Indeed, the state sponsored and supervised the production of lacquerware, which now had different schools of lacquer art producing common forms but with recognisably distinct designs. Lacquerware commonly took the form of plates, cups, and jars and similarly imitated metal vessels, but they were decorated more elaborately, particularly with scenes of mythical creatures appearing from behind clouds and probably representing the spirit world of the afterlife.