While ancient Chinese warfare was often characterised by large armies in pitched battles, siege warfare and the sacking of cities were also regular features. Huge earth walls with towers and encircling ditches or moats became the normal strategy of defence for most cities, even from the Neolithic period. Fortifications were also thought necessary to protect certain vulnerable stretches of state borders too, especially during the Warring States Period from the 5th century BCE. This strategy culminated in the Great Wall of China of the Qin and Han dynasty. Nevertheless, Chinese warfare was anything but passive and most commanders knew full well the limitations of a defensive policy based on a long and bitter history of fallen cities and, like their counterparts in other ancient cultures, they much preferred the mobility provided by chariots and cavalry or the advantages of pre-emptive strikes and quick withdrawal.

Early Fortifications

The first thing to do when considering the possible defence of a town or city was to select a geographically favourable site. For this reason, many ancient Chinese cities in the Neolithic period were built on hills and or near rivers to provide a natural obstacle to attacking forces. Even better was a raised site protected by a confluence of two or three rivers which was still high enough to avoid the risks of flooding. Next was to make access even more difficult by surrounding the settlement with a ditch, a practice with traceable remains dating back to the 7th millennium BCE but becoming a common practice in Neolithic times, especially at sites such as those of the Longshan culture (c. 3000-1700 BCE).

The excavated soil from ditches could be used to further raise the settlement site or build a rudimentary wall on the side of the ditch nearest the settlement. In addition, a local water source could be diverted to make the ditch into a moat and present an even more formidable obstacle to enemy soldiers. As warfare became a more common feature of daily life the moats became wider (up to 50 m) and deeper (up to 6 m) with the walls higher (up to 5m) and thicker (up to 25 m). However, it was not until the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) that siege warfare on fortified towns became a more common strategy when it was seen as necessary not only to defeat an enemy in the field but also wipe out their settlements.

Early fortifications may well have had an important social impact, as here summarised by the historian R. D. Sawyer:

Even though history shows that forces of destruction normally overwhelm constructively oriented efforts, the defensive solidity provided by the earliest walls and moats made possible the gradual accumulation of the goods produced by the weaving and handicraft industries, facilitated the domestication of animals, protected the emergence and expansion of agriculture, and harboured metallurgical workshops. It also fostered social cohesion and nurtured a sense of identity by separating the community from the external realm. (Sawyer, 2011, 406)

In addition, such consequences as accumulating goods and wealth within a defendable space may well have contributed to making these settlements a tempting target to covetous neighbours, thus leading to a necessity for even greater defences. Certainly, great wealth and power were needed in order to coerce a population into building the fortifications in the first place. There is ample evidence that both men and women in their thousands were required to provide their labour, conceived as a form of tax, to help build defensive fortifications which took years to construct. Slaves and criminals were used, too. During the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), for example, those convicted of such crimes as manslaughter had their forehead tattooed with the word chengdan, meaning “Wall Builder”, and so their required punishment was made known to all the world.

Once having constructed fortifications, there was the never-ending problem of maintenance to ensure the continued integrity of the structures, that the exterior of walls remained smooth and difficult to assault, and that ditches were not filled with rubble and undergrowth. The following ode, which dates to the Zhou period, describes the building of city walls:

Crowds brought the earth in baskets;

They threw it with shouts into the frames;

They beat it with responsive blows;

They pared the walls repeatedly, and they sounded strong.

Five thousand cubits of them arose together,

So that the roll of the great drum did not overpower them.

(Sawyer, 2011, 55)

Developments in Design

Defensive walls, over time, became more solid and more permanent as warfare became a more frequent reality of daily life. Cities used walls made from earth pounded and compressed (as in the ode above), using wooden beams and flat tools, which then became a highly weather-resistant and extremely hard material. Architects began to realise that different soils interspersed in a particular way gave added strength and stability. As walls became more imposing, and consequently much heavier, foundations had to be better prepared to bear the weight. The wall itself was made stronger by mixing in plant material, pottery sherds, sand, straw, and branches. A protective lower layer of river stones made earth walls more resistant to erosion, too.

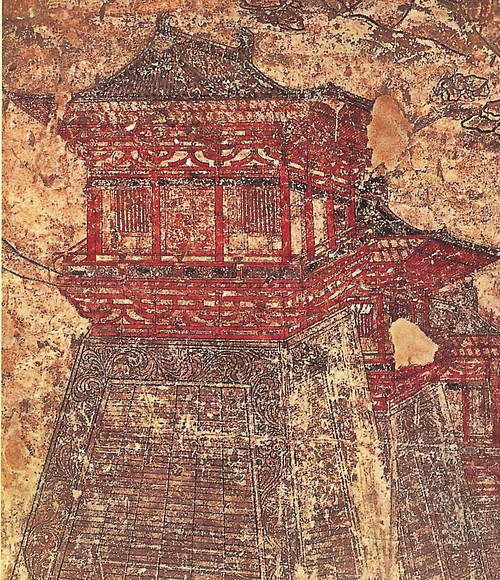

A double wall structure was increasingly employed, and then walls developed even further to be faced with stone or brick and buttressed with waist walls. From the 6th century BCE walls began to be reinforced with wood, had towers and monumental gates added, incorporated crenellations to protect archers, and, as cities expanded, whole new walls were built to encompass the growing suburban areas. The great capital city of Chang'an had impressive earth walls and towered gateways. The city's 5.3-metre high walls enclosed some 8,600 hectares (c. 21,250 acres). Such defences, and those at other cities, especially those near troublesome border regions, were really designed to protect the population only long enough for an army to be organised and sent to relieve them.

It is also true that massive walls were built not only for purposes of practical defence - many were much more massive than required for that function alone - but also to project power over the local populace and ensure outposts could be defended by a relatively small force, an important consideration as states expanded and an army had to cover a wide expanse of territory. It must also be true that impressive fortifications had an important psychological effect on an enemy and so would have acted as a deterrent which, with luck, never needed to be tested in actual battle. This idea is supported by ancient military treatises which actually listed and graded cities based on their defensive strength.

Attack & Defence

Such developments as towers in fortifications were in response to the frequently ingenious methods of attack they had to withstand. Armies equipped themselves with scaling ladders, battering rams and mobile towers, held protective covers while they charged the defences, set up prebuilt bridges made of wood and chains to cross moats, tunnelled away at foundations to make walls collapse from below, used artillery to fire destructive heavy missiles and incendiary bombs, diverted rivers to erode the walls, and even entered through a city's sewers if they could. The defenders met these attacks with bows, crossbows, and likely anything else they could throw down on the attackers from a great height. Heavier artillery crossbows worked by pulleys and winches came in handy for defence from the 4th century BCE onwards.

Defenders were not without their own peculiar innovations, either, as they used such devices as hollow pottery jars covered with a leather top and buried within their walls, thus, if anyone started tunnelling the pottery would resonate as a warning. Fires were also lit using such materials as dried mustard, which created a thick smoke which could be blown down attacking tunnels using bellows.

The moats should be deep and wide, the walls solid and thick, the soldiers and people prepared, firewood and foodstuffs provided, the crossbows stout and arrows strong, the spears and halberds well suited. This is the method for making defence solid. (From the 4th-3rd century BCE military treatise Wei Liao-Tzu, Sawyer, 2007, 253)

The Great Wall & its Predecessors

Even more ambitious than city walls were the attempts to build walls along state borders, especially during the Warring States period (c. 481-221 BCE), although the first such walls along the northern frontiers of China may have been built as early as the 8th century BCE. By the 5th century BCE and the situation of many major states all at war with each other, China became crisscrossed with defensive border walls. The Wei state, for example, built on its frontier with the Qin state a double border wall with each side being over six metres thick. The walls were themselves protected by huge square watchtowers built separate from them but within firing range. The historian G. Shelach-Lavi has this to say on the fortifications of the time:

The walls functioned not only to keep enemies out, but also to control the movements of subjects and keep them in. On a symbolic level, these walls served as enormous displays of the Warring States kings' power and their ability not just to build such huge monuments, but also to transform the physical landscape of their states. (276)

Most of these Warring States structures were dismantled when the Qin dynasty established itself as the sole ruler of China in 221 BCE, but they did keep some and even extended others, the most famous being, of course, what became known as the Great Wall of China. This great edifice was extended again during the Han dynasty and the Sui dynasty (581-618 CE) so that it stretched some 5,000 kilometres from Gansu province in the east to the Liaodong peninsula. The wall was not a continuous structure and had several breaks, designed as it was to help protect China's northern frontier against invasion from nomadic steppe tribes. Square watchtowers and beacon towers were built into the wall at regular intervals, and fast communication between them was possible by chariot riders having enough space to ride along the top of the walls. This was necessary because no standing army was stationed on the wall permanently, it being much too long for anything other than a regular patrol guard and the occasional camp.

It is also to be remembered that symbolic though the Great Wall has become of ancient China, many emperors preferred a policy of paying off the northern and western tribes which threatened the empire's borders in the form of tribute. This was far less costly than a war or even permanently stationing troops along China's lengthy frontiers. It is also true that in actual warfare Chinese commanders much-preferred attack to defence and pre-emptive strikes against troublesome neighbours was the usual method of maintaining the territorial status quo rather than sitting behind a wall waiting for the enemy to take the initiative.