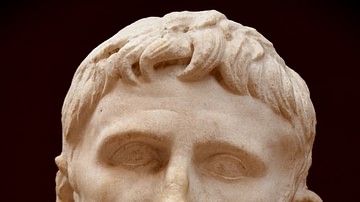

Augustus is well known for being the first Emperor of Rome, but even more than that, for being a self-proclaimed “Restorer of the Republic.” He believed in ancestral values such as monogamy, chastity, and piety (virtue). Thus, he introduced a number of moral and political reforms in order to improve Roman society and formulate a new Roman government and lifestyle. The basis of each of these reforms was to revive traditional Roman religion in the state.

Restoration of Monuments

First, Augustus restored public monuments, especially the Temples of the Gods, as part of his quest for religious revival. He also commissioned the construction of monuments that would further promote and encourage traditional Roman religion. For example, the Ara Pacis Augustae contained symbols and scenes of religious rites and ceremonies, as well as Augustus and his “ideal” Roman family – all meant to inspire Roman pride. After Augustus generated renewed interest in religion, he sought to renew the practice of worship.

Religious Reforms

In order to do so, Augustus revived the priesthoods and was appointed as pontifex maximus, which made him both the secular head of the Roman Empire and the religious leader. He reintroduced past ceremonies and festivals, including the Lustrum ceremony and the Lupercalia festival. In 17 BC, he also revived the Ludi Secularae (Secular Games), a religious celebration that occurred only once every 110 years, in which sacrifices and theatrical performances were held. Finally, Augustus established the Imperial Cult for worship of the Emperor as a god. The cult spread throughout the entire Empire in only a few decades, and was considered an important part of Roman religion.

Tax & Inheritance Laws

Augustus' goal in restoring public monuments and reviving religion was not simply to renew faith and pride in the Roman Empire. Rather, he hoped that these steps would restore moral standards in Rome. Augustus also enacted social reforms as a way to improve morality. He felt particularly strong about encouraging families to have children and discouraging adultery. As such, he politically and financially rewarded families with three or more children, especially sons. This incentive stemmed from his belief that there were too few legitimate children born from “proper marriages.” On the other hand, he penalized unmarried men older than 38 years old by imposing on them an additional tax that others did not have to pay. They were also debarred from receiving inheritances and attending public games. Furthermore, the Lex Julia de maritandis ordinibus prohibited celibacy and childless marriages, as well as made marriage compulsory.

marriage & divorce laws

Augustus also amended divorce laws to make them much stricter. Prior to this, divorce had been fairly free and easy. In addition, after Augustus' reforms, adultery became a civil crime instead of a personal crime under the Lex Julia de adulteriis coercendis. In other words, it became a crime against the state, which meant that the state (not just the husband) could take an adulterer to court if there was evidence of adultery. Penalties for adultery included banishment, or sometimes the husband or father of the adulterer could kill an adulterous wife. Augustus' own daughter, Julia, was banished for adultery after this new legislation. She was exiled to a desolate island called Pandateria.

Augustus also felt that people should not interact with or, especially, marry those outside of their own social class. As such, he created laws that reinforced hierarchical seating in the theatre and amphitheatre. For instance, front row seats were reserved for Senators, the next rows for equestrians, then the rest divided up for young men, soldiers, and so on.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Augustus was looked upon as a savior of traditional Roman values. His political, social, and moral reforms helped to bring stability and security, and perhaps most importantly, prosperity to the Roman world which had been previously rocked by internal turmoil and chaos. As a result, Rome's first Emperor eventually came to be accepted as one of the gods, and he left a unified, peaceful empire that lasted for at least another 200 years before new crises emerged in the 3rd century CE.