Icons, that is images of holy persons, were an important part of the Byzantine Christian Church from the 3rd century CE onwards. Venerated in churches, public places, and private homes, they were often believed to have protective properties. The veneration of icons split the Church in the 8th and 9th century CE as two opposing camps developed - those for and those against their use in Christian worship - a situation which led to many icons being destroyed and the persecution of those who venerated them.

Significance & Production

The word icon derives from the Greek eikon which is variously translated as 'image', 'likeness' or 'representation'. Although the term may apply to any representation of a holy figure (Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, apostle, saint or archangel) in a mosaic, wall painting, or as small artworks made from wood, metal, gemstones, enamel, or ivory, it is most often used specifically for images painted on small portable wooden panels. These panels were usually created using the encaustic technique where coloured pigments were mixed with wax and burned into the wood as an inlay.

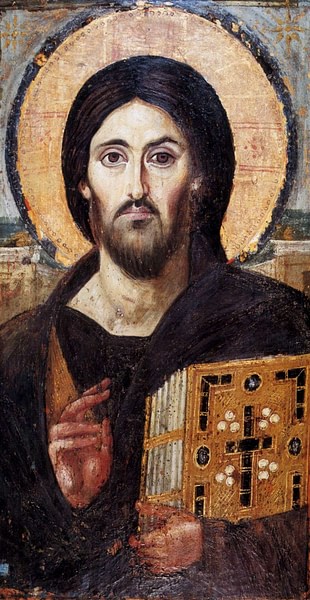

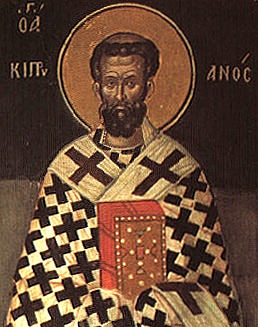

The subject in icons is typically portrayed full frontal, with either the full figure shown or the head and shoulders only. They stare directly at the viewer as they were designed to facilitate communication with the divine. Figures often have a nimbus or halo around them to emphasise their holiness. More rarely, icons are composed of a narrative scene. Not produced for art's sake, they were designed for devotional purposes and to help people better understand the figures they were praying to, and bridge the gap between the divine and humanity.

The artistic conventions seen in icons such as naturalism and the hierarchy of figures would influence Byzantine art in general. Another development was the iconostasis, a free-standing construction with the express purpose of housing an icon. These 'image stands' were often set up in the countryside, sometimes to commemorate a particular event or the site of an ancient church. Another type of iconostasis is the tall wooden screen seen in eastern churches which stands in front of the altar and is decorated with several icons.

The most revered of all icons were those classified as acheiropoietos, that is, not made by human hands but made by a miracle. These icons were often believed to have protective powers (palladia) not only over individuals but also over entire cities during times of war. One famous example is the icon of the Virgin Mary which was held responsible for protecting Constantinople during the siege of 626 CE when it was paraded around the Theodosian Walls by the bishop of the city Sergios. Indeed, this icon of Mary, in a pose where she holds the infant Jesus, known as Theotokos, gave rise to the city's second name as Theotokoupolis, "the city guarded by Theotokos". Byzantine ships frequently carried icons on their masts and armies carried them as banners in battle for the same reasons.

Finally, many ordinary believers had their own family icons in their homes or carried one on their person for divine protection much as earlier representations of pagan gods had been used and worshipped in a domestic setting independent of priest or temple. These small icons could take the form of miniature panels with a protective lid, necklaces, or pilgrim flasks made from clay or silver bearing an image of the holy figure subject to the pilgrimage made. As in churches, icons were prayed and bowed to, kissed, and had incense and tapers lit before them.

Controversy & Iconoclasm

The veneration of icons in Christianity has always had an ambiguous history, with the practice receiving as many critics as supporters. Critics of the practice cite the instructions given to Moses by God that the people of Israel should not worship idols or graven images as recorded in the Old Testament book of Exodus (20:4-5 and 34:17) and then repeated exactly in Deuteronomy (5:8-9). However, icons are known to have been produced from the 3rd century CE and to have become popular from the 6th century CE.

In the 8th century CE, the Byzantine Church was rocked by the movement of iconoclasm, literally the "destruction of images" which peaked in two periods: 726-787 CE and 814-843 CE. The historian T. E. Gregory here summarises the debate:

Iconoclast theologians began to see connections with the theological disputes of the past 400 years: they argued that images, in fact, raised once again the Christological problems of the fifth century. In their view, if one accepted the veneration of ikons of Christ, one was guilty of either saying that the painting was a representation of God himself (thus merging the human and the divine elements of Christ into one) or, alternatively, maintaining that the ikon depicted Christ's human form alone (thus separating the human and the divine elements of Christ) - neither of which was acceptable. (212)

Defenders of icons insisted that God could never be captured in art anyway and an icon is only ever one person's vision of that God. Consequently, there is no danger of such works becoming universal idols as they are a mere imperfect reflection of the divine reality. In addition, they have a useful function in helping the illiterate understand the divine. Such iconophile scholars as John of Damascus (c. 675 - c. 753 CE) also insisted that there was a difference between veneration and all-out worship:

When God is seen clothed in flesh, and conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter, who became matter for my sake, and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out my salvation through matter. I will not cease from honouring that matter which works my salvation. I venerate it, though not as God. (Gregory, 205)

The debate raged on for decades; Byzantine emperor Leo III (r. 717-741 CE) and his successor Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) were particularly vehement opponents of icons, with the former infamously destroying the largest icon in Constantinople, the golden Christ above his own palace gates. Constantine V was even more zealous and actively persecuted those who venerated icons, the iconophiles. The Pelekete monastery on Mt. Olympus was infamously burned down, and many others were stripped of their treasures. Mutilations, stonings, and executions were carried out on those who did not toe the line.

A second wave of iconoclasm arrived in the first half of the 9th century CE, especially during the reign of Theophilos (829-842 CE). The emperor decided to attack the very source of icons: the monks who produced them and so such noted icon-painters as Theophanes Graptos and his brother Theodore had their foreheads branded as a warning to others.

The issue not only split the Byzantine Church but the whole Christian world, with the Popes supporting the use of icons. When Leo III formally decreed in 730 CE that all icons must be destroyed, Pope Gregory III responded by stating that anyone guilty of such destruction would be excommunicated. The fierce debate was fuelled by political rivalries and the ongoing wrestle for supremacy in the Church between the east and west.

As a consequence of the controversy, a huge number of icons were destroyed or defaced with many wall paintings repainted with simple crosses, the only symbol permissible to the iconoclasts. A large number of icons were, though, saved and spirited away to the greater safety of the eastern parts of the empire. The issue was settled by Michael III (r. 842-867 CE) and Theodora, his regent mother, who had the veneration of icons proclaimed Orthodox in 843 CE. This official ending of the icon debate is still celebrated by Eastern Christians today as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” on the first Sunday of Lent.

Important Icons

The Kamoulianai icon was considered to have been created by a miracle. The image of Christ appeared on a linen cloth when it was immersed in water and this cloth was then taken to Constantinople in 574 CE. Once there, it was held responsible for certain miracles and was called upon to protect the city against the siege of 626 CE by the Avars, which ultimately failed.

The Hodegetria icon (“She who points the Way”) of Constantinople was a painted image of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus in her left arm while she points to Christ with her right hand. It was housed in the Hodegon monastery of the capital. It was believed to have been painted by Saint Luke, even if that tradition only developed from the 11th century CE. Unfortunately, the icon was cut into four pieces by the Turks who stormed Constantinople in 1453 CE and has since been lost. The image was much copied in Christian art, one of the most famous being the wall mosaic in the Church of the Panagia Angeloktistos at Kiti, Cyprus.

The Mandylion icon (the “Scarf”) was another miracle icon, probably the first of its kind, which had the image of Christ on it. According to the legend which is first recorded in the 6th century CE, Abgar V, the 1st-century CE king of Edessa in Syria became seriously ill and he called on Jesus Christ to cure him. Unable to visit in person, Christ pressed his face against a cloth, which left an impression, and then sent the cloth to Abgar. On receiving the gift, the king was miraculously cured. The image was copied in many wall-paintings and domes in churches around Christendom as it became the standard representation known as the Pantokrator (All-Ruler) with Christ full frontal holding a Gospel book in his left hand and performing a blessing with his right. Two of the most famous instances of the Pantokrator were in the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople and the church at Daphne (c. 1100 CE), near Athens.

The Mandylion was often cited in theological arguments for Christ's incarnation as a real man, and it was also the basis of depictions of Christ on Byzantine coinage. The Mandylion was taken from Edessa in 944 CE when the Byzantine general John Kourkouas took it in exchange for lifting his siege of the city. From there it was taken to Constantinople and kept in the royal palace. During the Fourth Crusade when Constantinople was sacked in 1204 CE, the Mandylion was taken as a prize to France. Alas, this most precious icon of all was destroyed during the French Revolution.

Many other important icons are dotted around the world in churches and museums but an especially large number are to be found in Rome and at the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai which has several dating to the 6th century CE, including a magnificent Pantokrator, probably donated by Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) to mark the monastery's foundation.