Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire involved the Christian faithful travelling often huge distances to visit such holy sites as Jerusalem or to see in person relics of holy figures and miraculous icons on show from Thessaloniki to Antioch. Well-worn routes resulted along which regular stopping points allowed pilgrims to sleep, eat, and be cared for in a network of monasteries and churches. For many pilgrims, their journey was the last they would ever make, and Jerusalem, especially, became a place where hospitals and hospices catered for the faithful until they were interred in the tombs they had pre-booked so as to rest in peace at the very centre of the Christian world.

Origins & Purpose of Pilgrimage

Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE), was one of the great founders of churches, notably in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and it was during her visit to the Holy Land in 326 CE that she claimed to have discovered the True Cross, that is the actual wooden cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified. Helena is widely credited with being one of the most important figures in making pilgrimage fashionable amongst devout Christians. The practice got another boost when Constantine himself made a visit to Jerusalem in 335 CE.

Pilgrimage really took off in the 5th and 6th centuries CE as other sacred sites sprang up across the empire. The skeletal remains, items of clothing, and tombs associated with holy figures, famous holy artworks and their potential for working miracles, the healing waters of sacred shrines, and even famous living holy men and women were all reasons for Christians to leave their homes and travel great distances. Pilgrimage in the Byzantine period was, though, less about making an arduous journey which had value in itself and more about getting to a final destination and being able to see and venerate Christianity's treasures in person, to actually be for a time in the places where wondrous things had occurred in the distant past, and by so doing reaffirm one's faith.

The travel plans of pilgrims were disrupted, if not actually ended, by the Arab conquest of the Levant by the mid-7th century CE. Byzantine armies reconquered parts of the Middle East in the 10th century CE, and the Crusaders, too, ensured a steady stream of pilgrims could still make the arduous journey to the Holy Land. Constantinople, too, was a major attraction to pilgrims from within and outside the empire's territories and remained so until the 15th century CE.

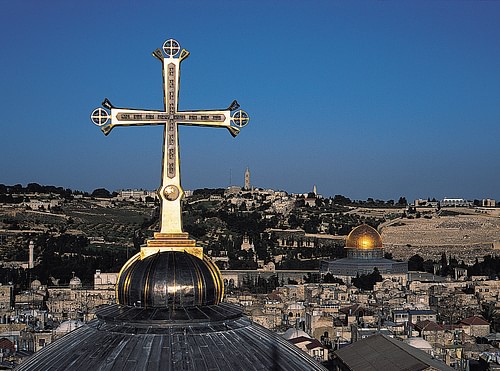

The Holy Land

Pilgrimage developed in the Byzantine period to such an extent that whole itineraries were made which spanned across the eastern part of the empire. The Holy Land was, of course, the most important and popular destination for pilgrims. Jerusalem was considered by Christians to be the centre of the world. The earliest surviving account of a Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem is by a pilgrim from Bordeaux who recorded his travels in 333 CE. The city really took off as a destination for pilgrims following Constantine I's 4th-century CE sacred building programme there. The emperor set up lavish shrines at the Holy Sepulchre on Golgotha, where Christ was crucified and then entombed, the Mount of Olives, where the Ascension took place, and the nativity cave in Bethlehem.

Other sites of interest in Jerusalem included the site of the Resurrection, Gethsemane, where Christ prayed on the eve of his death, the church of Holy Wisdom, where Christ was condemned, the birthplace of Saint Mary and her tomb, the cave of the Last Supper, and the tombs of Simeon and James. By the 4th century CE alone there were some 34 sites to be visited in the city and its environs, and these only grew over the centuries with more and more churches, especially, being built. Besides Bethlehem, other sites outside the city included the tomb of Lazarus in Bethany. There were also relics to be seen such as the very jugs which Jesus had used to turn water into wine at Cana and the notebook he had used as a child in Nazareth.

For many pilgrims, it was enough to visit the Holy Land and they had no thought of returning home. Many of the faithful wished to spend their dying days there, and hospices and monasteries sprang up to cater for them. Houses were rented out and tombs were built, all of which helped the Church fulfil its charity work for those pilgrims who could not pay their way.

A Network of Sites

Although the final destination of many pilgrims might have been Jerusalem, there were, along the way, many other stops of interest such as shrines set up in honour of important Christian figures. These shrines, dedicated to saints, martyrs and men and women who had witnessed Christ's ministry, were usually furnished with impressive buildings or were part of monasteries that tended the shrines and offered accommodation to weary pilgrims. Travellers needed plenty of stops because their progress was slow, limited as they were to walking or riding a donkey. Ships made the voyage in quicker time, but even when they arrived at the Holy Land, there were still large distances to be covered. For example, a trip from Jerusalem to Mount Sinai, where Moses saw the burning bush and received the Ten Commandments, could take two weeks.

Other Important Sites

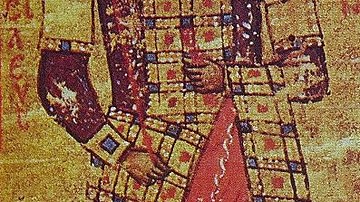

The skeletal remains of Thomas the Apostle made Edessa in Syria a popular pilgrimage site which also had the prized mandylion, a holy cloth which had the impression of Christ on it. The image was copied in many wall-paintings and domes in churches around Christendom as it became the standard representation known as the Pantokrator (All-Ruler) with Christ full frontal holding a Gospel book in his left hand and performing a blessing with his right. Following the city's siege in 944 CE the mandylion was taken to the royal palace in Constantinople.

From the late 4th century CE Abu Mina near Alexandria was a major pilgrimage site as it boasted the tomb of Saint Menas, a martyr who died during the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). The site was a typical martyrion or martyr's tomb with several splendid basilicas built around it. Especially popular in the 5th and 6th century CE, Abu Mina, like many other such sites, demonstrates that Christian shrines were often supported by imperial patronage.

Qal'at Seman, just north of Antioch was another popular attraction as that was where the famous ascetic Symeon the Stylite the Elder (c. 389-459 CE) had stood on his column for 30 years in order to better contemplate God. When Symeon died, the site became one of pilgrimage with an octagonal church, two monasteries, several inns, and four basilicas built around the original column.

Ephesus was traditionally considered the home of several important holy Christian figures: Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Timothy, and Mary Magdalene. All had major shrines just outside the city, and John's tomb was especially popular as the dust that was thought to regularly emit from its cracks was considered a cure-all. There was also the red stone said to have been used by Joseph of Arimathea when he washed the body of Christ prior to burial, a piece of the True Cross that John the Evangelist had worn around his neck, and the bonus attraction of the cave of the Seven Sleepers: seven young Christians who, under persecution in the mid-3rd century CE, had hidden in a cave and miraculously slept there for two centuries before emerging back into the world again.

Other major pilgrimage sites on every dedicated pilgrim's bucket list (and their associated holy figures,) included Seleucia in southern Asia Minor (Saint Thekla) with its impressive fortified monasteries, Hierapolis in Syria (Philip the Apostle), Euchaita in central Asia Minor (Saint Theodore), Myra in south-east Asia Minor (Saint Nicholas), Rome (Saint Paul and Peter), and Thessaloniki, where Saint Demetrius had a massive basilica dedicated to him.

Finally, Constantinople, was itself, of course, an important point of pilgrimage, especially as emperors steadily removed relics from other cities. Jerusalem, for example, was plundered when it became increasingly threatened by the Arab caliphates. The mandylion and True Cross, as already noted, ended up in the Byzantine capital, as did the Crown of Thorns, the shroud, girdle and veil of the Virgin Mary, and the relics of the Apostles Luke, Timothy, and Andrew. There were many icons to be seen too, notably, the very first one said to have been painted by Saint Luke. Indeed, the city acquired such ecclesiastical riches that it became known as the New Jerusalem. Constantinople might have lost many of its treasures in 1204 CE during the Fourth Crusade but it acquired other relics over time and remained an attraction for pilgrims, especially from Russia, up to the 15th century CE.

Holy Relics

For those who could not make it all the way to the Middle East or one of the other major sites, there was at least the chance to see relics and souvenirs in shrines elsewhere. Ornate receptacles were made (reliquaries) and put on display in shrines and churches across the empire which contained a portion of earth from the Mount of Olives, for example. Even holier relics included fragments of the bones or clothing of martyrs or pieces of wood and nails from the True Cross that Saint Helena had brought back to Constantinople and which subsequently spread across Christendom. These very holy items were often not on public display, or at least not permanently so that when they were put before the public gaze in their gem-studded boxes and ornate silver ampules, the effect was all the more mesmerising. Such rare public processions of relics and icons, perhaps only occurring once each year, were themselves a magnet for pilgrims.

As the super-special first-hand holy relics were obviously in short supply, a whole secondary range of semi-relics (brandea) sprang up consisting of items which had been in contact with the original holy relics, oil being a prime example. Even representations of holy figures could take on a spiritual significance of their own. Icons are frequently recorded as having miraculously bled or wept, the figure's eyes may have moved or their halo glowed, all in response to a believer's prayers. Whatever the form, access to relics and their spin-offs allowed pilgrims and believers to feel a little closer to the holy individuals they revered.

Pilgrim Souvenirs

Pilgrims could purchase take-home souvenirs at many sacred sites, the most popular being blessed oil, water or earth from the holy location itself or which had been in contact with a holy relic. These liquids were kept in distinctive flat circular bottles, known as a pilgrim flasks (ampullae). Often highly decorated, they were usually made of terracotta but finer ones were made using tin and lead. The substance within the flasks was believed by many to function as an amulet, as a medicine or even as a miracle cure.

Another souvenir, used for much the same purposes as the bottles, was the small disks made from pressed earth which had previously been sanctified. These medallions were decorated with a stamped blessing or image of a saint. In the case of Symeon the Stylite's pilgrims, they got small tablets stamped with the ascetic's image. Painted panels, ivory panels, and engraved prints were similarly bought as it was believed that, like the medallions, they had all somehow been in touch with a holy person - either directly having had contact with the person's tomb or relics or simply because they represented that figure and had come from the holy site itself. Finally, for the big spender, there was the enkolpion which was an ornate necklace containing an icon or even an actual fragment of a holy relic. For pilgrims, all of these items acted as a tangible link to the divine, and they were frequently thought to protect the holder and ensure they overcame the dangers of ancient travel and finally got home safely.