Hatshepsut, whose name means "Foremost of Noble Women" or "First Among Noble Women" (royal name, Ma'at-ka-re, translated as "spirit of harmony and truth") was the fifth ruler of the 18th Dynasty (r. 1479-1458 BCE). She was the daughter of Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose and, as was common in Egyptian royal houses, married her half-brother Thutmose II. They had a daughter together, Neferu-Ra, and Thutmose II had a son by a minor wife named Isis, Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE), whom he named as his heir. Although she was made regent until Thutmose III came of age, she had long been acquainted with a position of power and chose instead to have herself crowned pharaoh of Egypt. She was a woman in a man's position and understood she needed to take measures to protect herself as ruler, so she chose to depict herself as a daughter of the god Amun, the most popular and powerful deity of the time.

Traditional Male Monarchy & the God's Wife of Amun

Hatshepsut reigned during the period known as the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 to c. 1069 BCE), which began with the expulsion of the foreign Hyksos from Egypt by Ahmose of Thebes (c. 1570-1544 BCE). Ahmose began a policy of creating buffers around the borders of Egypt to make sure no foreign rulers could take control of the country as the Hyksos had. The pharaohs who preceded Hatshepsut expanded on Ahmose's policy, including, of course, her father Thutmose I who led campaigns into Syria and Nubia.

Hatshepsut continued these kinds of campaigns early in her reign but needed further legitimacy to consolidate her hold on power. As a female pharaoh of Egypt, she was breaking with a long tradition. The first ruler of Egypt was thought to be the god Osiris, who established balance and harmony among the people of the land until he was murdered by his brother Set. According to Egyptian mythology, Osiris' wife, Isis, brought him back to life, but because he was incomplete, he could no longer rule on earth and descended into the underworld where he became Lord of the Dead. His son, Horus, then took his place after avenging his murder.

Following this paradigm, the monarchs of Egypt were always male. The king patterned his rule on the just example of Horus and, when the king died, he identified with the king of the afterlife Osiris. There was no place in this model for a female ruler. In the Middle Kingdom, however, the god Amun began to gain popularity in Egyptian religion. The Theban prince Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) united Egypt at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and made Thebes the capital. Amun, to whom credit for the victory was given, became Thebes' patron god. Under the reign of Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE), the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak in Thebes was begun, and Amun steadily gained in prestige and power.

The honorific God's Wife of Amun was bestowed on noble women who would assist the High Priest of Amun in his duties, usually the wife or daughter of the king. In the time of the Middle Kingdom, the duties of God's Wife of Amun were little more than singing and assisting the male clergy, but by Hatshepsut's time, the role carried more weight. Hatshepsut was appointed God's Wife of Amun by her mother and came to know the intricacies of the cult firsthand as well as the power of authority.

Hatshepsut the Pharaoh

Thutmose II died in 1479 BCE, appointing Hatshepsut as regent to the young king. Thutmose III, though a child, officially ruled with Hatshepsut until 1473 when she declared herself pharaoh, had herself represented in male attire, and took on the duties and obligations of the male pharaohs who had preceded her. Perhaps to solidify her hold on the throne, she married her daughter Neferu-Ra to the young Thutmose III (a marriage which would last eleven years until Neferu-Ra's death). The marriage of her daughter to the heir-apparent was not enough, however, and so Hatshepsut re-created herself in an image she was sure the Egyptian court and people would not only accept but admire. She would be not only God's Wife in name but related to the god intimately as his daughter. In her inscriptions she relates how it was not really Thutmose I who was her father but the god Amun himself:

He [Amun] in the incarnation of the Majesty of her husband, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt [Thutmose I] found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. She awoke at the divine fragrance and turned towards his Majesty. He went to her immediately, he was aroused by her, and he imposed his desire upon her. He allowed her to see him in his form of a god and she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty after he had come before her. His love passed into her body. The palace was flooded with divine fragrance.

(van de Mieroop, 173)

As a God's Wife of Amun, Hatshepsut had learned the language of the clergy and understood the rituals associated with the god. She had danced and sung for the god at the beginning of the festivals when the God's Wife was supposed to arouse the deity for the act of creation. By identifying herself as the daughter of the god she was now elevating her status beyond the semi-divine position of a ritualistic God's Wife to that of an actual daughter of the god. To further strengthen her hold on the throne of Egypt she also had inscribed an oracle which she claimed was given long before her birth in which Amun foretold that she would become pharaoh:

An oracle before this good god magnificently predicted for me kingship of the Two Lands, with the north and the south fearing me; and it gave me all the foreign lands, illuminating the victories of my Majesty. Year 2, second month of the growing season, day 29, the third day of the festival of the god Amun...being the foretelling to me of the Two Lands in the broad hall of the Southern Opet (=Luxor Temple), while his Majesty [Amun] delivered an oracle in the presence of this good god. My father, the god Amun, Chief-of-the-Gods, appeared in his beautiful festival.

(van de Mieroop, 173)

As a God's Wife of Amun, Hatshepsut would have known of the oracles of the god – oracles which would eventually be taken so seriously that Amun was the de facto ruler of Thebes and Upper Egypt – and so this claim of an oracle predicting her rise to power and the legitimacy of her rule as Amun's daughter would have carried a great deal of weight with the people of Egypt. Having married her daughter to her successor, and established herself as the daughter of the most popular god in Egypt – a god considered the creator and redeemer, the king of all the gods – Hatshepsut set about to rule her country and create her legacy.

Public Works

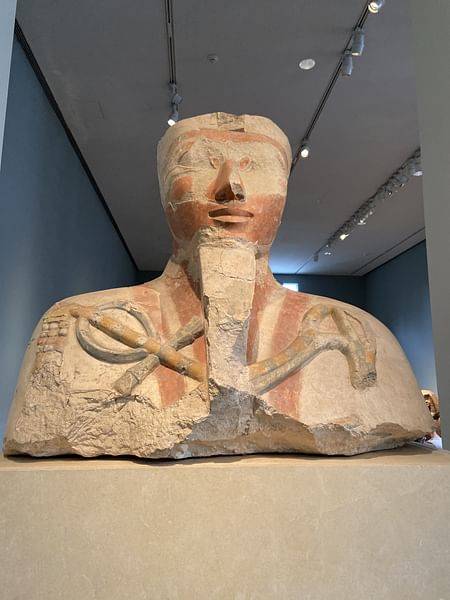

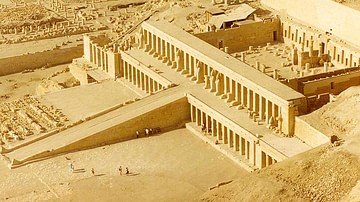

Hatshepsut immediately went to work on great public works projects, commissioning her exquisite temple at Deir el-Bahri at Thebes early on. In reliefs carved at this site Hatshepsut claims divine origin as the daugher of the god Amun and so clearly states her right to rule Egypt legitimately. She further claimed that her father, Thutmose I, had made her his co-ruler and heir during his reign before her marriage to Thutmose II. Her chief steward, Senenmut, who had served Thutmose II, and was her loyal companion, corroborated these stories as, it seems, he helped the queen in all of her affairs of state. Historians Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs comment on her building projects writing:

Hatshepsut proceeded to feminize Egypt. Her reign included no great military conquests; the art produced under her authority was soft and delicate; and she constructed one of the most elegant temples in Egypt against the cliffs outside the Valley of the Kings. Built beside the famous mortuary temple of Montuhotep I, Hatshepsut's version elongated the original design to produce a different aesthetic. A long ramp ascended to a wide terrace from a courtyard filled with pools and trees. Bordered by a sweeping wall of columns, the terrace stretched the length of Montuhotep's entire temple, and held a ramp that ascended to a second terrace, also lined by a sweeping wall of columns. Atop its columned halls, whose walls were covered with lovely carvings, stood the temple proper whose smaller rooms contained statues of the queen. Some wall scenes showed her birth as a divine event in which the god Amun, disguised as her father Thutmose I, impregnated her mother, indicating that the god had personally placed her on the throne. (30)

The reign of Queen Hatshepsut lasted 22 years, and in that time, she was responsible for more building projects than any pharaoh in history save Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses the Great, 1279-1213 BCE). Although historians recognize her rule as one of peace and prosperity there is evidence that, early on, after she had claimed descent from Amun, she led military expeditions against the neighboring countries of Syria and Nubia. She sent expeditions to the land of Punt (present-day Somalia) in ships seventy feet long, each manned with 210 sailors and 30 rowers. These expeditions brought back, among other things, live frankincense trees in baskets of their native soil (the first time in history that plants or trees were transported from a foreign land successfully for transplant) and had them situated to adorn her complex at Deir el-Bahri. This complex boasts perfect symmetry and was so awe-inspiring to the ancients that later pharaohs would choose the locale around her temple for their own tombs, an area known today as the Valley of the Kings.

Removal from History

Around 1457 BCE, Thutmose III, whom Hatshepsut had elevated as general of her armies, led a campaign out of Egypt to suppress a revolt at Megiddo and, after this, Hatshepsut disappears from history. Her shrines were mutilated and her obelisks and monuments were torn down, most likely under the order of Thutmose III. So thorough was the work of Thutmose III that Hatshepsut's name was forgotten, and her reign was virtually unknown at the beginning of the 19th century CE. It was not until the orientalist Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) deciphered the Rosetta Stone and read the inscriptions inside her temple at Deir el-Bahri that anyone knew such a pharaoh had ever existed.

The motive behind the desecration and destruction of Hatshepsut's works, the erasure of her name from history, is not known. For many years, it was speculated that Thutmose III resented a woman essentially usurping his throne, but there is no evidence anywhere to support this. To eliminate the likeness or name of a person from a temple or statue after that person's death was to, essentially, kill their spirit in the Egyptian afterlife, and there is no evidence that Thutmose III bore such enmity for Hatshepsut. Another theory is simply that Thutmose III wanted to convey to history the idea of an unbroken line between his father and himself, but this theory also fails in that Thutmose III only had public images of Hatshepsut erased while maintaining those statues, paintings, and reliefs in the interior of temples.

Perhaps the best theory advanced for Thutmose III's actions is that he was trying to restore balance and feared that the illustrious reign of a woman would inspire other women in ancient Egypt to seek positions of power reserved, by the gods, for males. As noted, pharaohs were supposed to follow the paradigm of Osiris and Horus in maintaining balance in the land; not of Isis nor of any other female deity, even though such goddesses were held in high esteem. The concept of ma'at (universal harmony and balance) was of utmost importance to the Egyptians and, as a son of a king who had too long been kept from his throne by a woman, Thutmose III may have felt he was simply performing his duties as pharaoh in eliminating evidence of a female ruler. The result of all his work was that, until the latter part of the 19th century, the most famous female ruler of Egypt was the last pharaoh Cleopatra VII (c. 69-30 BCE) of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, who was not even Egyptian, but Greek.

Hatshepsut's Legacy

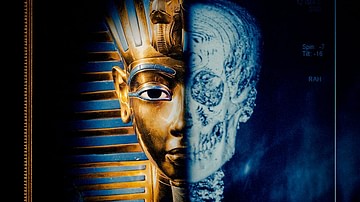

It is held that Hatshepsut's corpse was hidden from Thutmose III and was given an Egyptian burial in secret for fear he would desecrate the corpse. For many years it was believed that nothing was left of her body save some fragments found in a canopic jar along with Hatshepsut's nurse Sitire-Ra. In 2006, however, the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass claimed to have located Hatshepsut's mummy on the third floor of the Cairo Museum. Researchers identified the mummy by matching a tooth known to be Hatshepsut's with an empty socket in the mummy's jaw and DNA testing with Hatshepsut's grandmother.

Examination of the mummy showed that Hatshepsut died in her fifties from an abscess following the removal of a tooth. The theory that Thutmose III bore his stepmother some great enmity has been largely discredited, although it is still advanced by some scholars. The attempt to eliminate Hatshepsut from history was no doubt due to her stepson's understanding of Egyptian culture and the traditional role of women who, even though they enjoyed a higher status than their sisters in other ancient cultures, were still considered secondary to males.

Hatshepsut was not the first woman to rule Egypt. Niethotep, queen of King Narmer, may have ruled after his death in the First Dynasty of Egypt and, only a little later, Queen Merneith is thought to have ruled, even if only as regent, Nimaethap acted as regent for her son Djoser in the Third Dynasty of Egypt and Queen Sobekneferu reigned in the 12th Dynasty. She was not the last either as Twosret would reign briefly in the 19th Dynasty after her. Still, Hatshepsut reigned longer than any other woman and, further, ruled over an incredibly prosperous and powerful nation.

It is a credit to her understanding of her people and culture that she recognized the importance of presenting herself as a daughter of Amun, a living embodiment of the divine. Through her careful manipulation of religious belief, she was able to legitimize her rule, but the success of her incredible reign is due entirely to her personal abilities as a leader who saw what needed to be done and was able to do it well.

Her legacy is important to note, not only for women who are competing with men for positions of power but also for anyone who feels disenfranchised and powerless in society. Certainly, Hatshepsut began her life with advantages, being the daughter of a king, but she refused the traditional role assigned to women and discarded even her parentage in order to become who she knew she really was: the daughter of Amun and pharaoh of Egypt.