O Creator of the material world, at what distance from the holy man (should the place for the dead body be)?" Ahura Mazda replied: "Three paces from the holy man". (Vend. 8. 6-7)

In September 2009 CE, one of my relatives suggested that we visit “an ancient and mythical cave”. The story behind this cave is that a man (commoner) had abducted an elite girl. He took her to that cave and married her. They lived together for many years and, finally, both were buried there after their death. This is one of the versions of this mythical story; many variations I have also heard of since then.

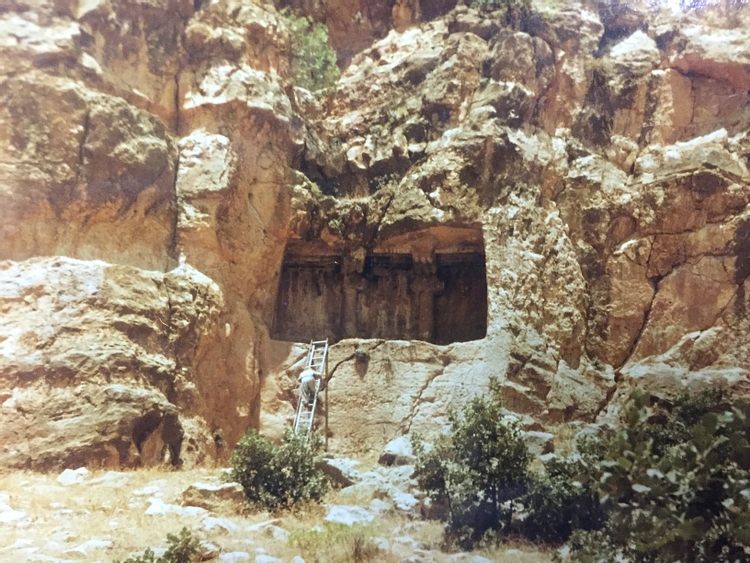

The façade and entrance into the rock-cut tombs of Ashkawt-i Qizqapan (Kurdish: The Cave of the Ravisher or the Cave of the Raped/Abducted Girl), which lies near Zarzi village and the Palaeolithic cave of Zarzi, Chemi Rezan Valley, Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraqi Kurdistan. It is not a cave; it is a rock-cut tomb, which contains 3 tombs in 3 different burial chambers. It dates to the Median-Achaemenid Period, 600-330 BCE. The entrance into the tomb lies approximately 8 meters above the ground level. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Name & Origins

Finally, we were there. He said this is Ashkawt-i Qizqapan (ئه شكوتي قزقاپان). The word “Ashkawt (ئه شكوت) is a Kurdish one, which means a cave; this is the Sorani dialect and accent of the people of Sulaymaniyah. Qizqapan (قزقاپان) is a Turkish word, which means a rapist or ravisher. The cave is also known as the cave of the abducted girl (Kurdish: ئه شكوتي كچه دزراوه كه). Western scholars use the word “Ishkewt”, not “Ashkawt”, when they describe that ancient cave; therefore when you Google the internet, type Ishketw-i Qizqapan!

Approximately, 65 kilometres north-west of the modern city of Sulaymaniyah (35°48'36.09"N; 45° 0'23.35"E), lies Ashkawt-i Qizqapan. It is not a cave; it is a rock-cut tomb, which was carved into a steep cliff of a small mountain. It is not a single tomb; there are three separate burial chambers, each contains a coffin. Because it lies inside a cliff, local people call it a cave.

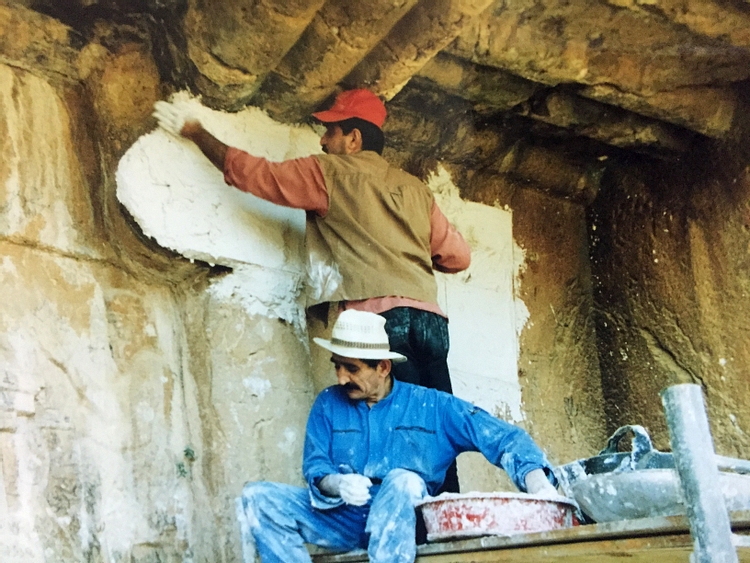

In late 2002 CE, the Directorate General of Antiquities of Sulaymaniyah started a conservation and restoration project on this ancient tomb. The façade of the tomb was restored (the whole façade was and is still bombarded with modern writings, paintings, memories, bullet marks, etc.). A modern replica of the façade was made and was placed at the main entrance to the halls of the Sulaymaniyah Museum. An iron ladder was placed so that tourists can easily access the tomb; in the early 2010s CE, that ladder was replaced by a larger double ladder.

Iraqi Kurdistan contains only two rock-cut tombs; Ashkawt-i Qizqapan and Ashkawt-i Kur w Kich (Kurdish: ئه شكوتي كوڕ و كچ). The latter means the Cave of the Boy and Girl and lies some distance from Ashkawt-i Qizqapan. It is more simplified and lacks many iconographies and the stunning art of the former.

Two important questions have never been answered; when precisely was the tomb carved and who were the people who were buried there? The cliff of the mountain, which houses the tomb looks over a valley, where a small river passes through. Mr Hashim Hama Abdullah, Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, told me that one day he asked a local farmer about that valley. The farmer told him that several times when he was ploughing his field, human bones came out of the earth. No tombstones are/were present. Therefore, Hashim suggests that the whole area seems to be an ancient (but not Islamic) cemetery. It is a well-known tradition in the near East that people entomb their dead beside or around a shrine or a tomb of a religious scholar. Accordingly, was Ashkawt-i Qizqapan a well-known sanctuary?

The façade (or we may call it the antechamber) of the tomb was decorated and carved with a single relief (a scene), three emblems (two rounded and one square-shaped), and two engaged columns. The capitals of the columns support a roof. The latter was carved in a way that resembles a wooden roof with eaves.

The antechamber lies about 8 meters above the ground level within the cliff. Hashim said that it appears that the area in front of the antechamber was smoothed out so the that the tomb becomes high and inaccessible. In addition, he said that there are some traces of a path which leads to the antechambers, not from the ground level, but from the right or left borders, high above the cliff.

This high level of the tomb and inaccessibility may simply prevent people from accessing it, right? Was that the intention? But, was this “high burial” part of a religious tradition of entombing people? The façade is full of signs of vandalism; people went there and wrote down their memories, names and stories! So, it is not that difficult after all if you want to go there in the absence of a built-in ladder or pathway. It is not (and was not) a local tradition to bury dead bodies high up in a cliff. We may presume that this style of architecture is outlandish or obtrusive. Therefore, who were the people who brought with them this method of burial and architecture?

Something striking that the whole tomb and its three burial chambers lack any inscription, of any kind. No writings and no language. But, can we presume that there were inscriptions and they were erased later? The constellation of multiple iconographies and the variations from already known ones have created a dilemma; to which period in the history does this tomb belong? Let us see the images and discuss them.

Columns

The overall depiction of those two ionic-style columns seems to be thick and short in addition to having unusually massive capital volutes. The single plinth is square, and the torus is rounded. The surface of the shaft is smooth and displays no flutes and fillets. The capital sits on a narrow neck. The volutes of the capital seem abnormally large and flank a plant or a rose, with petals and leaves. There is a pair of honeysuckles on the inner side of the volute. The motif of “egg-and-dart” was carved on the abacus. Overall, this is reminiscent of Iranian-type of columns. A roof, shaped like a wooden wall with eaves, sits on the abacus and completes the upper part of the antechamber.

Divine Emblems

There are three divine emblems, carved higher up on the façade. Two are rounded, and appear as roundels, and the third one is a sunken relief within a rough square.

A. The Astral Emblem:

This emblem was set on the façade, at the right side of the capital of the right column. There is a central rounded circle or boss, surrounded by 11 rays (or petals). On the top of the latter, there are oval cups or roughly half-circles. Traces of the original red paint can clearly be recognized on the upper rays, suggesting that the façade was painted with vibrant colours. What does this emblem represent? Is it a rosette, astral device, or sun? The star-burst of Ishtar-Anahita was suggested by Professor Zainab Bahrani. Scholars of the Sulaymaniyah Museum (Kama Rashid and Hashim Hama Abdullah) say that this may be the Lydian goddess Artimus. Whatever it was, the nearby lunar crescent (of the adjacent centrally-placed rounded divine emblem) may well suggest that this is an astral divine representation. Once again, there is no clear consensus on what this emblem tells us.

B. The Lunar Crescent:

A close-up image of the central roundel of the divine emblem at the façade of the rock-cut tombs of Ashkawt-i Qizqapan. This image was shot just before the restoration/conservation work, which was carried out by the Directorate General of Antiquities of Sulaymaniyah in late 2002 CE. The date of the image is October 24, 2002 CE. Note the modern writings and the modern sketch of a human figure riding on a horseback (vandalism) as well the traces of the original red colour on the crown and the dark green robe. Photo courtesy Hashim Hama Abdullah.

This rounded emblem was placed midway between the inner margins of the volutes of the columns' capitals, above the main centrally-carved relief. A bearded crowned figure, looking to the left, sits within a circle. He appears to rise up from the lower part of the circle, which was thickened to resemble a lunar crescent. His right arm holds a long cup or a barsom (a ritual object used in Zoroastrianism) while the left hand, which faces up, holds an unrecognized oval object. He wears a long robe. The barsom was suggested by Bahrani while the long cup was mentioned by Rashid and Abdullah. Traces of the original red paint on the crown and the dark green pigment on the robe can be recognized. Who is this figure? If it is a god, which one? Rashid and Abdullah suggested that this is a representation of Sin, the moon god, while Bahrani stated that this a god sitting on a crescent moon (without naming this god).

C. Ahura Mazda:

The aforementioned rounded emblems were placed at an approximately similar level. The third square-shaped emblem was placed at a little bit lower level than the above two roundels, at the left margin of the left capital. This asymmetrical placement, as well as the square shape of the emblem, had spoiled the symmetry, balance, and regularity of the façade's decoration; this might well have suggested that this emblem was not planned to occupy that area, or it was added later.

Within this square, a bearded, crowned, and winged figure looks to the left. His upper body (from above the mid-chest appears within a ring. There is a pair of ribands and a single tail. The overall depiction, when superficially scanned, is reminiscent of Ahura Mazda; however, there are some differences or variations. This figure has two pairs of wings; one pair is horizontal and straight while the other pair is curled upwards towards the figure's head. The figure's wings are composed of two (upper and lower) rows of feathers surrounding a central bone-like structure; the wingtips are feathered and fill in the gap between the outer ends of the upper and lower rows of feathers. The feathers of both pairs of wings are different in shape and size. Is this figure Ahura Mazda?

Mithra was the supreme deity of Medes (who had practised Mithraism). This Mithra worshipping or pre-Zoroastrian Mazdaism was an ancient Iranian religion. The first depiction of the “stepped fire altar” appeared during the Median era. However, there is no consensus whether an early form of Zoroastrianism was common among the Medes. Ahura (mighty) Mazda (wisdom) is the creator and sole god of Zoroastrianism. The first documented appearance of this god was below the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great (reigned 522-486 BCE). Early in the Achaemenid period, Ahura Mazda was invoked alone. However, during the reign of Artaxerxes II (405-358 BCE), Ahura Mazda was invoked together with Mithra and Anahita, as a triad. Images of Ahura Mazda continued to appear during the Parthian Era. However, towards the end of the Parthian Period and the beginning of the Sassanid Period, the widespread iconoclasm had virtually destroyed all images of Ahura Mazda. During the Sassanid Era, Ahura Mazda was depicted as a dignified male figure, standing or sitting on a horseback, as part of their Zurvanism (a heretical form of Zoroastrianism).

The Main Scene

The core and striking feature of the façade of the antechamber is the presence of a centrally carved relief, between the two engaged columns and just above the entrance to the central burial chamber. There are two men, flanking a stepped altar topped by a semicircle.

The man on the left is a little bit taller than the right one and his body/clothes appear compact and thicker than those of the right man. This may suggest that the left man is higher in rank than the right one and/or is older in age. They stand and face each other, raise their right hand in reverence or salutation, while their left hand grasps the upper end of a compound (double convex) Parthian-like bow. The lower end of the bows is straight and sits at (or behind) the tip of their left shoes. The upper end of the bow is curved forward. Both men wear a similar headdress, which has covered the whole scalp, ears, cheek, and neck; this headdress is called “tiara”. It is not clear whether their mouth was covered by the same fabric of the tiara or by a separate piece of cloth (like the Magi of Zoroastrianism). Those Magi, to protect the sacred fire of the stepped altar from their breath, cover their mouth with a separate piece of cloth (like the modern medical facial masks). Part of their forehead hair, the upper part of their moustache, and the lower part of their beard appear. This headdress is Median in style and is called “bashlyk”.

Detail of the relief carved at the façade of the rock-cut tombs of Ashkawt-i Qizqapan. This man stands on the left side. He wears what appears to be a “tiara”; a headdress which covers the head, neck, ears, cheeks, and chin. This headdress is Median in type and is called a “bashlyk”. In addition, a piece of cloth covers the mouth (very similar to the Magi of Zoroastrianism, who wore such a fabric to protect the sacred fire from their "polluted" breath). The forehead hair, moustache, and beard are clearly seen. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The man on the right side wears the typical Median attire; long calf-length tunic and loose trousers. The man on the left also wears some long tunic and loose trousers but, in addition, he wears a “kandys”; a cloak or coat with long empty sleeves, which hangs loose downward on the sides and is draped over the shoulders. This kandys always reminds me of the chapan worn by the former president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karazai! Once again, the men's attire is Median. Therefore, both men appear Median.

They wear shoes and there is a strap of “leather” encircling the mid-foot just in front of the ankle joint. Dr Mouaid Al-Damirchi of the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities (now retired and living in Amman, Jordan) suggested that this type of foot suggests a Hatra Period.

What are they doing? They seem to greet each other or perhaps are performing a ritual before the stepped altar. The semi-circle sitting on the altar is different from the classical pyramid-shaped depiction of the sacred fire of Zoroastrianism. Therefore, does this semi-circle represent a modified form of that fire? The absence of weapons in the men's right hands very likely represents a peaceful event; it is a well-known local tradition to hold a weapon in the right hand when a man meets his rival during periods of hostility or conflicts.

The most important question now is: who are they? Kings, local rulers, warriors, elites, or nobles? The overall depiction most likely indicates that they are elites/nobles. The absence of inscriptions or any captions has left us confused; who are they, precisely?

Rashid and Abdullah stated that:

- The right man is the Lydian king Alyattes (reigned 610-560 BCE).

- The left man is the Median king Cyaxares (reigned 625-585 BCE).

- The depicted scene marks the end of the military conflicts between those kings. The Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus (reigned 556-539 BCE) said to have mediated this reconciliation. The worshipping of the moon god Sin was not practised by the Medes; therefore, why was the lunar crescent depicted on the façade, centrally, between and above the two men? Rashid and Abdullah concluded that this representation of the crescent moon refers to Nabonidus.

- The right-sided rounded divine emblem is the Lydian goddess Artimus, who accompanies the Lydian king.

- Ahura Mazda blesses Cyaxares.

However, this analysis and explanation were not mentioned by any other scholars. The whole scene remains a mystery.

Burial Chambers

From the antechamber, through a roughly square doorway, we can enter the central burial chamber. Through similar doorways, on the right and left sides of this room, we can go to the right and left burial chambers, respectively.

Within each room, there is a rectangular coffin within the floor, which was hollowed out to form this rocky grave. The upper part of each coffin has a rim for what appears to be a stone lid. Each coffin lies beside a wall, at one of the corners of the rooms. The length of the base of the coffins is too small to accommodate a supine and outstretched human corpse. Either these graves were astodans (where the exposed bones of the dead body were gathered and relocated here) or, very unlikely, they were graves for children. I will not discuss the dimensions of the rooms and coffins, but the central coffin is a little bit larger than the two others. The walls of the burial chambers do not display any drawings, inscriptions, or reliefs. The doorway leading to the central chamber as well as the doorways of the right and left rooms were not sealed or closed; no trace of any material (wood, iron, or stone) remains to indicate what was used to seal off the rooms. The coffins are entirely empty, and their covering lids are absent; not even a piece of bone is present. The burial chambers and their coffins were looted in antiquity. Full stop!

Finally, were the dead bodies entombed simultaneously or sequentially? No one knows the answer. The place of the tombs and the decoration of the façade undoubtedly required highly skilled workers to carve these rock-cut tombs for an elite family, whose name remains unknown.

Rashid and Abdullah's opinion is that the tombs are Median and that would give a date of 600-550 BCE; this is consistent with the conclusions of Taha Baqir, Fouad Safar, and Tawfiq Wahbi. However, several other scholars (such as C. J. Edmonds, Mary Boyce and Frantz Gerent, and Zainab Bahrani) have concluded that the iconography of the art is Achaemenid and that the tombs date back to the 6th (after 550 BCE) and 5th centuries BCE. A noteworthy point to highlight is that the mountain of the tombs and the area surrounding it have never undergone any excavation work.

This marvellous piece of art and architecture proudly occupies the cliff, spreading its scent of history, and embracing the eternal souls of some vanished human bones.

Acknowledgment:

A special gratitude goes to Mr Hashim Hama Abdullah (Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum) and the Archive Department of the Sulaymaniyah Museum for their kind help and cooperation, and for the wonderful pictures of Qizqapan they have provided me with.