Illuminated manuscripts are, as their name suggests, hand-made books illumined by gold and silver ink. They were produced in Western Europe between c. 500 and c. 1600 CE and their subject matter is usually Christian scripture, practice, and lore. The books are elaborately illustrated and their illumination comes from the use of brightly-colored inks painted on top of or ornamented by gold and silver ink.

Even though many manuscripts from the medieval period are often referred to as “illuminated”, the term technically applies only to those which make use of gold and silver ink. The fragments of a manuscript of Virgil's works, for example, is often included in a discussion of illuminated manuscripts but does not technically meet the standard definition.

The most popular type of illuminated manuscript was the Book of Hours, which was comprised of Christian prayers to be said at certain hours throughout the day. Some of these are the most impressive works of their periods, elaborately decorated with intricate illustrations and lavishly illumined. More of these books have survived than any other because the demand for them was greater and so more were produced on commission.

Other types of illuminated manuscripts were copies of the Bible or just the four gospels, bestiaries, prayer books, biblical tales, and those which dealt with classical writers such as Virgil or Homer. These manuscripts were produced by monks in monasteries, abbeys, and priories and were quite costly because they took so long to make.

Only people of substantial means were able to afford to commission them. In time, nuns also began producing the manuscripts in their nunneries and, as literacy grew and books became more popular, professional book-makers became involved in order to meet the growing demand.

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in c. 1440 CE marked the beginning of the end of hand-made, illuminated books, but they remained popular among the wealthy, and some collectors, in fact, disdained printed books and continued to commission hand-made works. Even though Gutenberg's press made books less costly and more available, it took about 20 years for print books to become a profitable venture. Gutenberg himself, in fact, never profited from the invention; his press was seized for debt shortly after its invention and any profits were made by his patron Johan Fust who perfected Gutenberg's techniques and popularized the printed word.

Some of the most impressive illuminated manuscripts were actually created after Gutenberg's invention and continued to be produced into the 17th century CE. Although there are many fine works, from the beginning of their production onwards, which are considered great works of art, the following are among those considered the greatest. They are listed in order of date of composition.

The Greatest Illuminated Manuscripts

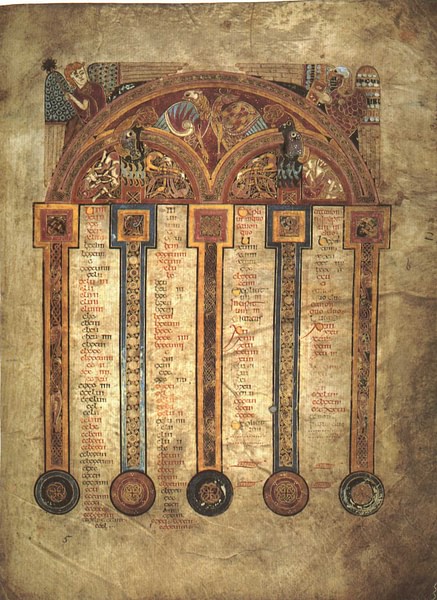

The Book of Durrow (650-700 CE) – The oldest illuminated book of the gospels created either at Iona or Lindisfarne Abbey. Scholar Christopher de Hamel describes the work:

It includes twelve interlaced initials, five full-page emblematic figures symbolizing the Evangelists, and six carpet pages, an evocative term used to describe those entire sheets of multicolored abstract interlace patterns so characteristic of early Irish art. Anyone can see that it is a fine manuscript. (20)

The book contains a number of striking illustrations and the carpet pages de Hamel makes note of are often adorned by intricate Celtic knot motifs entwined with animal imagery. The book was most likely used by missionaries as it is slim and, as de Hamel observes, “could easily slip into a traveller's saddle-pack” (20). The work marks the first appearance of the Evangelists in illuminated manuscripts as well as the earliest known use of gold and silver ink to illumine the gospels.

Codex Amiatinus (c. late 7th to early 8th century CE) – The oldest version of St. Jerome's Vulgate Bible. It was created in Northumbria, Britain, of 1040 sheets of fine vellum. The biblical narratives are illustrated by striking images brightly colored, although it is not technically “illuminated” since it makes no use of gold or silver ink. The work frequently devotes complete pages to these images which are known as “miniatures” in discussing illuminated manuscripts. It deserves a place among the greatest of these manuscripts for the mastery of its artwork.

Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 700-715 CE) – Created at the Lindisfarne Priory on the “Holy Island” off the coast of Northumberland, Britain. It is an illustrated edition of the gospels of the New Testament made in honor of the priory's most famous member, St. Cuthbert, and dedicated to the Glory of God. The priory was sacked by the Vikings in 793 CE – the first recorded Viking raid on Britain – but the book was somehow saved and moved to Durham, away from the coast, for safety. Along with the Book of Kells, the Lindisfarne Gospels is among the best-known and most admired illuminated manuscripts.

The Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) – Created either at Iona Abbey, Scotland, and brought to Kells, Ireland, in 806 CE or made at Kells, this is the most famous illuminated manuscript. The work is commonly regarded as the greatest illuminated manuscript of any era. Entomologist and palaeographer J.O. Westwood comments:

Ireland may justly be proud of the Book of Kells. This copy of the Gospels, traditionally asserted to have belonged to St. Columba, is unquestionably the most elaborately executed manuscript of early art now in existence, far excelling, in the gigantic size of the letters in the frontspieces of the Gospel, the excessive minuteness of the ornamental details, the number of its decorations, the fineness of the writing, and the endless variety of initial capital letters, with which every page is ornamented, the famous Gospels of Lindisfarne. (Book of Kells Chapter, 2)

Westwood here repeats a common misconception regarding the Book of Kells – that it was produced, or at least owned, by St. Columba (521-597 CE) who founded the abbey at Iona. Recent scholarship, however, has firmly established that the work was produced no earlier than c. 800 CE.

St. Albans Psalter (c. 1120 to c. 1145 CE) – Created at St. Alban's Abbey in Britain, this is a lavishly illustrated and illuminated book of Psalms and literature. It was commissioned by the scholar Geoffrey de Gorham who was abbot of St. Alban's between 1119-1146 CE. It was either made for or later given to Geoffrey's close friend Christina of Markyate (c. 1098 to c. 1155 CE), a visionary prioress whom he held in high esteem. The Psalter is widely admired for the detail and beauty of the artwork. It contains over 40 illustrations, all magnificently bordered and intricately wrought, designed to complement and honor the subject matter.

The Morgan Crusader Bible (c. 1250 CE) – Created in Paris and most likely for Louis IX (1214-1270 CE) who participated in the 7th and 8th Crusades and died of dysentery at the start of the 8th. The Morgan Crusader Bible was originally a work only of full-color illustrations, but later owners seem to have felt compelled to add text to complement the images. This practice is the complete reverse of how illuminated manuscripts were usually created, where the text was written first and then handed to an artist to illustrate and an illuminator to adorn. The purpose of the original work, without text, seems to have been the same as later: to present biblical narratives in an accessible form. Even so, the work contains a number of fascinating lay subjects having nothing to do with the Bible accompanying biblical text. The Morgan Crusader Bible is considered one of the greatest illuminated manuscripts of all time and an artistic masterpiece of the Middle Ages.

The Westminster Abbey Bestiary (c. 1275-1290 CE) – Created most likely in York, Britain. A bestiary is a book of animals, real or imaginary, defined and accompanied by illustrations. This genre originated in Greece in the 2nd century CE but was most popular during the Middle Ages when a number of them were produced to show a correlation between the natural world and the Christian vision of the Bible. The Westminster Abbey Bestiary is a fine example of this type of work. Drawing on both pre-Christian and biblical stories, the book presents an array of fascinating creatures across its 164 illustrations, each one represented in striking detail.

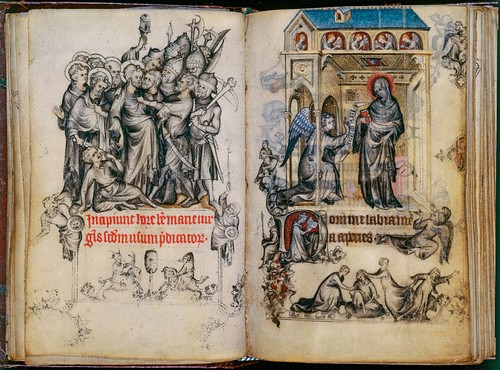

The Book of Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux (c. 1324-1328 CE) – Created in Paris, France by the leading illustrator of the time, Jean Pucelle, for the queen Jeanne d'Evreux (1310-1371 CE), wife of Charles IV (1322-1328 CE). It is an amazing artistic masterpiece of 25 full-page paintings representing the life of Jesus Christ as well as a number of smaller illustrations, totaling over 700. The text, of course, presents the prayers a faithful Christian would recite throughout the day, and the illustrations are intended to inspire and elevate the reader. The work is all the more impressive for its size: it is smaller than a modern-day paperback. Among the many surviving examples of a Book of Hours, this is easily one of the most impressive.

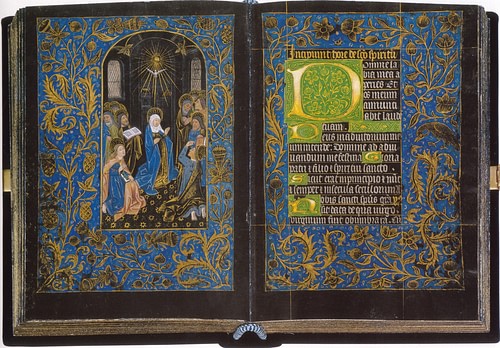

The Black Hours (c. 1475-1480 CE) – Created in Bruges, Belgium by an anonymous artist working in the style of the leading illustrator of the city, Wilhelm Vrelant who dominated the art c. 1450 CE until his death in 1481 CE. It is made of fine vellum which was carefully processed, stained black, and then illuminated in brilliant – almost mesmerizing – blue and gold. The images in blue and lighter colors are highlighted by the deep black of the background and the whole work gives a reader the impression of entering another realm. The text of the work adds to this impression as it is written in silver and gold ink. It is one of the most unique Books of Hours extant and easily one of the most impressive illuminated manuscripts.

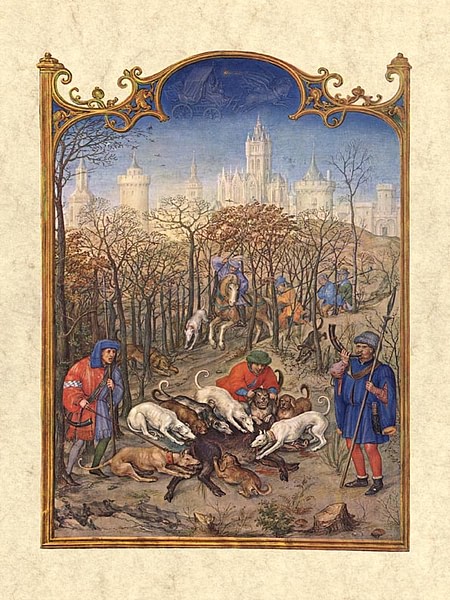

Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412-1416 and 1485-1489 CE) – Even though The Black Hours is recognized and admired for its unique qualities, Les Tres Riches Heures is the most famous Book of Hours in the present day. It is regularly referenced as an absolute masterwork. The book was commissioned by Jean, Duke of Berry, Count of Poitiers, France (1340-1416 CE). It was left unfinished when the Duke, as well as the artists working on it, died of the plague in 1416 CE. The manuscript was discovered and completed between the years 1485-1489 CE. It is often referenced as the “king of illuminated manuscripts” because of the incredible grandeur of the miniatures and the obvious artistic skill required to create it. Biblical themes are brought vibrantly to life by the illustrators and illuminated so brilliantly that the images seem almost to move on the page. The work contains other images such as landscapes of the time, domestic scenes, a plan of Rome, and others not associated with biblical stories.

Grimani Breviary (c. 1510 CE) – This work is nearly legendary for its length and the beauty of the artwork. The book is comprised of 1,670 pages with full-page illustrations of scenes from the Bible, secular legend, and contemporary landscapes along with domestic scenes. The text is biblical in nature and includes prayers, psalms, and other selections from the Bible. It was probably made in Flanders but who created or commissioned it is unknown. The book was bought by the Venetian Cardinal Domenico Grimani (1461-1523 CE) in 1520 CE who declared it so beautiful that only select people of high moral standing should be allowed to see it and then only under special circumstances. In his will, Grimani stipulated that the book could never be sold and left it to Venice.

Prayer book of Claude de France (c. 1517 CE) – Created for Claude, the queen of France (1514-1524 CE) along with an almost equally impressive Book of Hours. This work is one of the most unique illuminated manuscripts owing to its size: small enough to fit in the palm of one's hand. As a prayer book, it would have been easily carried and read and its utilitarian purpose could have been met without illustrations. What makes the work so fascinating is that it is illustrated with 132 intricate images framed by elaborate and striking borders. Some of these images are so small that, today, they cannot be seen without the aid of a magnifying glass. Scholars remain in disagreement, in fact, on how these images were produced since the magnifying glass did not exist at the time the book was created.

Conclusion

As printed books became more popular in the 1460s CE, those who made books by hand became highly esteemed by collectors. Scholar Giulia Bologna writes:

Even though it took at least six months for a speedy professional copyist to produce a single copy of a four-hundred-page book, printing did not immediately bring to an end the production of manuscripts. For the cultural, social, and political elites, illuminated manuscripts for long maintained a special prestige. Vespasiano de Bisticci claims that the great bibliophile Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, would have felt shame to have had a printed book in his library. (39)

The artists who worked on books such as the Grimani Breviary or the Prayer Book of Claude de France were working during a time when printed books were more widely accepted than they had been previously, but still, those who could afford to commission them preferred the beauty and craftsmanship of a hand-made, hand-illustrated work.

Publishers recognized this and tried to make their products appear more “legitimate” by decorating their covers with gold leaf and hiring illustrators to provide images for chapter headings, but for many years after the invention of the printing press, the wealthy continued to demand books made by hand, and among these are some of the greatest illuminated manuscripts of all time.