The Battle of Manzikert (Mantzikert) in ancient Armenia in August 1071 CE was one of the greatest defeats suffered by the Byzantine Empire. The victorious Seljuk army captured the Byzantine emperor Romanos IV Diogenes, and, with the empire in disarray as generals squabbled for the throne, nothing could stop them sweeping across Asia Minor. Manzikert was not a terrible defeat in terms of casualties or immediate territorial loss, but as a psychological blow to Byzantine military prowess and the sacred person of the emperor, it would resound for centuries and be held up as the watershed after which the Byzantine Empire fell into a long, slow, and permanent decline.

Byzantium & the Seljuks

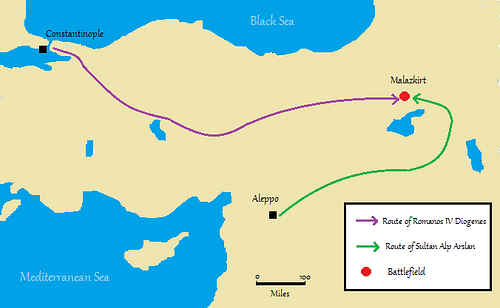

Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068-1071 CE), himself formerly a general, had inherited a Byzantine army in poor shape with inadequate arms and an overreliance on unreliable mercenaries and undisciplined conscripts. His predecessor Constantine X Doukas (r. 1059-1067 CE) had purposely expanded the state civil service, invested heavily in renovating Constantinople and completely neglected the army. Even worse, the empire was over-stretched with too many borders to defend. The Seljuks, in particular, were proving troublesome in Asia Minor. This nomadic tribe from the Asian steppe was of Turkish origin, and they had been repeatedly raiding Byzantine outposts, notably sacking Melitene in 1058 CE and Caesarea in 1067 CE. This necessitated the emperor into strengthening the fortresses around Lake Van which protected the routes into the region from Armenia and central Asia. The Byzantine emperor successfully campaigned in the region in 1070 CE, then, in March 1071 CE, he decided for one monumental push to rid Armenia, and anywhere else for that matter, of the Seljuks once and for all.

The Seljuk leader was Alp Arslan (r. 1063-1073 CE) and, along with an empire now covering Iran, Iraq, and most of the Near East, the sultan had at his disposal an army of highly skilled and mobile horsemen. Romanos' army was big, according to some sources it had 300,000 men, although modern historians prefer a figure of 60-70,000, still double that of the Seljuks. Whatever the size, one indisputable fact was that Romanos' army consisted of a hotchpotch of conscripts and mercenaries which included the Pechenegs and Uzes of the Eurasian Steppe, and even a contingent of Normans led by Roussel de Bailleul. The latter figure, an infamous adventurer, was highly suspect in his loyalty to the cause and was really only looking out for a choice kingdom of his own.

Prologue

On arrival in Armenia in August 1071 CE, Romanos split his force into two. One half was sent north of Lake Van under the command of the general Joseph Tarchaneiotes. The other half, led by the emperor and his general Nicephorus Bryennius, headed for the small fortress of Manzikert which was taken without much bother. Meanwhile, just what happened to Tarchaneiotes is uncertain. Byzantine sources are strangely quiet, and Muslim sources describe a victory for Arslan. The general was experienced, and given the size of his force, it seems unlikely he was wholly defeated. Tarchaneiotes may have deserted the cause, perhaps out of loyalty to a rival claimant to the Byzantine throne, or perhaps he even harboured imperial ambitions of his own. Whatever the exact circumstances, the result was that Romanos was left with half the army he had started out with.

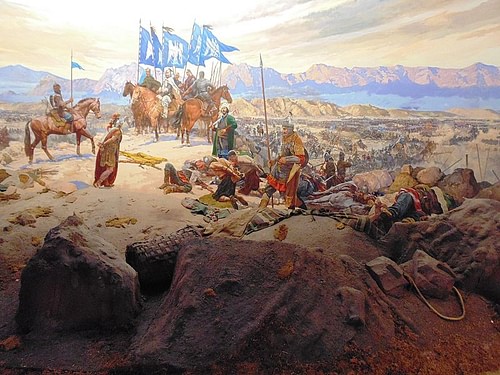

Battle

The two leaders and their armies finally met on 25 August near Manzikert, and a skirmish followed which resulted in the Byzantines being harassed by the Seljuk bowmen and Nicephorus Byrennius receiving three, albeit superficial, wounds. Almost immediately after the real fighting started, the Normans turned about and fled. Some of the Uzes mercenaries switched sides, too. The sporadic engagements, nevertheless, continued into the second day. Then the Seljuk leader, with his own difficulties to pay his soldiers and, in any case, far more interested in Syria, sent a delegation offering a truce. Romanos rejected it.

Romanos lined up his army for a full-on and decisive confrontation with several rows of infantry, his cavalry on the wings and himself dead centre. The 11th-century CE Byzantine historian Michael Psellos, in his biography of Romanos, criticises the emperor for donning armour like an ordinary soldier and hacking away at the enemy without any concern for his person or his responsibility as overall commander. Arslan, meanwhile, was more circumspect and consistently withdrew his forces in a crescent formation, allowing the Byzantines to advance but at the same time become increasingly exposed to the Seljuk archers who harassed the enemy flanks on horseback. As the light began to fade at the end of the day, Romanos ordered his troops to return to their camp.

Then disaster struck as the Seljuks swept forward against the retreating Byzantine cavalry. In the chaos, a large body of Byzantine troops panicked when they thought the emperor had been killed. The rumour had been started by one of Romanos' rivals, Andronikos Doukas, and the consequence was a disordered collapse of the Byzantine lines, a separation of the Byzantine rearguard from the main body and then encirclement by the Seljuk mounted archers. The left flank of the army tried to come to the aid of Romanos who was being overwhelmed in the centre but were pushed back by the enemy. The defeat was total, and Romanos, his horse killed from under him and with a wound to his sword hand, was captured. An eyewitness, Michael Attaleiates, gives the following vivid description of the debacle:

It was like an earthquake: the shouting, the sweat, the swift rushes of fear, the clouds of dust, and not least the hordes of Turks riding all around us. It was a tragic sight, beyond any mourning or lamenting. What indeed could be more pitiable than to see the entire imperial army in flight, the Emperor defenceless, the whole Roman state overturned - and knowing that the Empire itself was on the verge of collapse? (In Norwich, 240)

Romanos' Capture

According to Michael Psellos, the captive emperor was not treated at all badly by Arslan but was released from his chains when identified. After a submissive kiss of the ground before the feet of Arslan, who then placed his boot symbolically on the emperor's neck, Romanos was well fed for a week and even allowed to nominate any of his fellow captives for freedom. The 11th-century CE Scylitzes Chronicle also gives a full account of the capture, including the famous episode in which Arslan asked Romanos what he would have done if the positions had been reversed. Romanos was said to have replied “I'd have flogged you to death” whereupon the Muslim Arslan replied that I “will not imitate you. I have been told that your Christ teaches gentleness and forgiveness of wrong. He resists the proud and gives grace to the humble” (quoted in Psellos, 358). Nothing worse than being captured and preached to.

True to his word, though, Arslan released Romanos but only did so after he promised to give a personal ransom to the Seljuk leader, agreed to cede to him Armenia as well as the major cities of Edessa, Hieropolis, and Antioch, and offered one of his daughters to marry a son of the Seljuk leader. There was also the matter of a tribute: first, a one-off payment of 1.5 million gold coins to be followed by a hefty annual tribute of 360,000 gold coins.

Aftermath

Unfortunately for Romanos, his joy at freedom was short-lived for when he returned to Constantinople he was deposed and blinded, the throne taken over by a rival general Michael VII Doukas (r. 1071-1078 CE). Although the material losses to the Byzantine army were not huge at Manzikert, there were two lasting effects. One was on the psyche of the Byzantines having lost, albeit temporarily, their emperor. The other was more practical and significant. With Romanos' reputation tainted by the debacle, there was a mad scramble by many commanders in the provinces of Asia Minor to return to Constantinople and claim the throne for themselves. The civil war which ensued and the lack of the army's full support for Michael VII seriously weakened the empire's ability to resist the Seljuks in the longer term. Thus, Arslan and his successors continued to raid Asia Minor at will, establishing the Sultanate of Rum with their capital at Nicaea c. 1078 CE and even capturing Jerusalem in 1087 CE.

1071 CE had proved to be a disastrous year for the Byzantine Empire in more ways than one as, besides Manzikert, Bari was lost to the Norman king Robert Guiscard and Byzantine control in southern Italy was thus finally extinguished. Michael VII's reign would not meet with any more success than his predecessor's. Within the empire, rising prices and political unrest developed into several military rebellions which would eventually oust the emperor. The Byzantines would only see a return to stability and the empire regain some of its former glory with the reign of Alexios I Komnenos from 1081 CE, himself a veteran of the fateful battle at Manzikert.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.