The Egyptians believed the afterlife was a mirror-image of life on earth. When a person died their individual journey did not end but was merely translated from the earthly plane to the eternal. The soul stood in judgement in the Hall of Truth before the great god Osiris and the Forty-Two Judges and, in the weighing of the heart, if one's life on earth was found worthy, that soul passed on to the paradise of the Field of Reeds. The soul was rowed with others who had also been justified across Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to a land where one regained all which had been thought lost. There one would find one's home, just as one had left it, and any loved ones who had passed on earlier. Every detail one enjoyed during one's earthly travel, right down to one's favorite tree or most loved pet, would greet the soul upon arrival. There was food and beer, gatherings with friends and family, and one could pursue whatever hobbies one had enjoyed in life.

Work in the Afterlife

In keeping with this concept of the mirror-image, there was also work in the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians were very industrious and one's work was highly valued by the community. People, naturally, held jobs to support themselves and their family but also worked for the community. Community service was compulsory in `giving back' to the society which provided one with everything. The religious and cultural value of ma'at (harmony) dictated that one should think of others as highly as one's self and everyone should contribute to the benefit of the whole.

The great building projects of the kings, such as the pyramids, were constructed by skilled craftsmen, not slaves, who were either paid for their skills or volunteered their time for the greater good. If, whether from sickness, personal obligation or simply lack of desire to comply, one could not fulfill this obligation, one could send someone else to work in one's place - but could only do so once. On earth, one's place was filled by a friend, relative, or a person one paid to take one's place; in the afterlife, however, one's place was taken by a shabti doll.

The Function of the Shabti

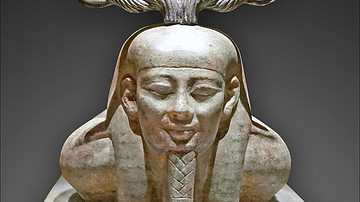

Shabti dolls (also known as shawbti and ushabti) were funerary figures in ancient Egypt who accompanied the deceased to the after-life. Their name is derived from the Egyptian swb for stick but also corresponds to the word for `answer' (wsb) and so the shabtis were known as `The Answerers'.

The figures, shaped as adult male or female mummies, appear in tombs early on (when they represented the deceased) and, by the time of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) were made of stone or wood (in the Late Period they were composed of faience) and represented an anonymous `worker'. Each doll was inscribed with a `spell' (known as the shabti formula) which specified the function of that particular figure. The most famous of these spells is Spell 472 from the Coffin Texts which date from c. 2143-2040 BCE. Citizens were obligated to devote part of their time each year to labor for the state on the many public works projects the pharaoh had decreed according to their particular skill and a shabti would reflect that skill or, if it was a general `worker doll', a skill considered important.

As the Egyptians considered the after-life a continuation of one's earthly existence (only better in that it included neither sickness nor, of course, death) it was thought that the god of the dead, Osiris, would have his own public works projects underway and the purpose of the shabti, then, was to `answer' for the deceased when called upon for work. Their function is made clear in the Egyptian Book of the Dead (also known as The Book of Coming Forth By Day) which is a kind of manual (dated to c. 1550-1070 BCE) for the deceased providing guidance in the unfamiliar realm of the afterlife.

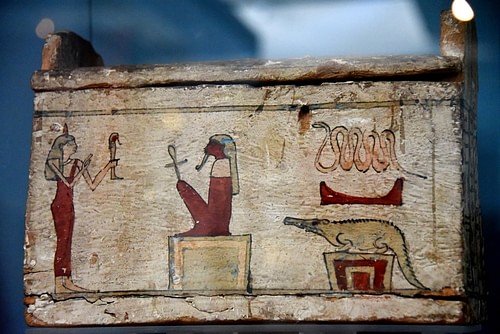

The Book of the Dead contains spells which are to be spoken by the soul at different times and for different purposes in the afterlife. There are spells to invoke protection, to move from one area to another, to justify one's actions in life, and even a spell "for removing foolish speech from the mouth" (Spell 90). Among these verses is Spell Six which is known as "Spell for causing a shabti to do work for a man in the realm of the dead". This spell is a re-worded version of Spell 472 from the Coffin Texts. When the soul was called upon in the afterlife to labor for Osiris, it would recite this spell and the shabti would come to life and perform one's duty as a replacement. The spell reads:

O shabti, alloted to me, if I be summoned of if I be detailed to do any work which has to be done in the realm of the dead; if indeed obstacles are implanted for you therewith as a man at his duties, you shall detail yourself for me on every occasion of making arable the fields, of flooding the banks or of conveying sand from east to west; `Here am I', you shall say.

The shabti would then be imbued with life and take one's place at the task. Just as on earth, this would enable the soul to go on about its business. If one were out walking one's dog by the river or enjoying one's time under a favorite tree with a good book and some fine bread and beer, one could continue to do so; the shabti would take care of the duties Osiris called on to be performed. Each of these shabtis was created according to a formula so, for example, when the spell above references "making arable the fields" the shabti responsible would be fashioned with a farming implement.

The Evolution & Importance of Shabti Dolls

Every shabti doll was hand-carved to express the task the shabti formula described and so there were dolls with baskets in their hands or hoes or mattocks, chisels, depending on what job was to be done. The dolls were purchased from temple workshops and the more shabti dolls one could afford corresponded to one's personal wealth. In modern times, therefore, the number of dolls found in excavated tombs has helped archaeologists determine the status of the tomb's owner. The poorest of tombs contain no shabtis but even those of modest size contain one or two and there have been tombs containing a shabti for every day of the year.

In the Third Intermediate Period (c.1069-747 BCE) there appeared a special shabti with one hand at the side and the other holding a whip; this was the overseer doll. During this period the shabti seem to have been regarded less as replacement workers or servants for the deceased and more as slaves. The overseer was in charge of keeping ten shabtis at work and, in the most elaborate tombs, there were thirty-six overseer figures for the 365 worker dolls. In the Late Period (c. 737-332 BCE) the shabtis continued to be placed in tombs but the overseer figure no longer appeared. It is not known exactly what shift took place to render the overseer figure obsolete but, whatever it was, shabti dolls regained their former status as workers and continued to be placed in tombs to carry out their owner's duties in the after-life. These shabtis were fashioned as the earlier ones with specific tools in their hands or at their sides for whatever task they were called upon to perform.

Equality in Death

Shabti dolls are the most numerous type of artifact to survive from ancient Egypt (besides scarabs). As noted, they were found in the tombs of people from all classes of society, poorest to most wealthy and commoner to king. The shabti dolls from Tutankamun's tomb were intricately carved and wonderfully ornate while a shabti from the grave of a poor farmer was much simpler. It did not matter whether one had ruled over all of Egypt or tilled a small plot of land, however, as everyone was equal in death; or, almost so. The king and the farmer were both equally answerable to Osiris but the amount of time and effort they were responsible for was dictated by how many shabtis they had been able to afford before their death.

In the same way that the people had served the ruler of Egypt in their lives, the souls were expected to serve Osiris, Lord of the Dead, in the afterlife. This would not necessarily mean that a king would do the work of a mason but royalty was expected to serve in their best capacity just as they had been on earth. The more shabti dolls one had at one's disposal, however, the more leisure time one could expect to enjoy in the Field of Reeds. This meant that, if one had been wealthy enough on earth to afford a small army of shabti dolls, one could look forward to quite a comfortable afterlife; and so one's earthly status was reflected in the eternal order in keeping with the Egyptian concept of the afterlife as a direct reflection of one's time on earth.