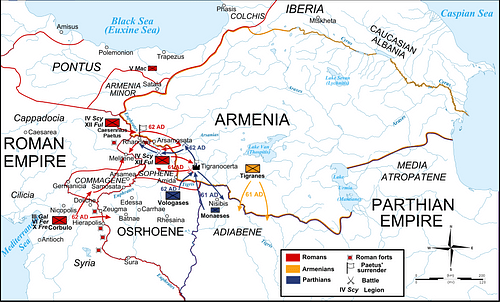

The Roman-Parthian War of 58-63 CE was sparked off when the Parthian Empire's ruler imposed his own brother as the new king of Armenia, considered by Rome to be a quasi-neutral buffer state between the two empires. When Parthia went a step further and declared Armenia a vassal state in 58 CE all-out war broke out. The on-off war, in which the Roman commander Corbulo excelled, would only be settled in 63 CE with the Treaty of Rhandia which shared the responsibility of ruling Armenia between the two powers.

The Armenian Throne

Tiridates I of Armenia (r. c. 63 to 75 or 88 CE) was the brother of the Parthian king Vologases I (aka Vagharsh, r. c. 51- up to 80 CE, dates disputed) who invaded Armenia in 52 CE for the specific purpose of setting Tiridates on the throne. The Roman Empire was not, though, content to passively permit Parthia into what they considered a buffer zone between the two great powers. Nor was it willing to accept the consequent dent in Roman pride and prestige. Further, an embassy arrived in Rome which represented the pro-Roman faction in Armenia and they asked for direct assistance. Consequently, Roman emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE) sent an army in 54 CE to at the very least restore the status quo. The commander given the task was Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, Rome's best general at the time.

Corbulo, a man of imposing stature, had gained his reputation fighting in Germany to restore Roman influence in the region. The modern historian M. Lovano gives the following summary of the Roman historian Tacitus' (c. 56 - c. 120 CE) description of Corbulo:

His greatest hero in the Annals is definitely Corbulo, victor over the Parthian menace. Corbulo is capable of great physical endurance, is as hard-working as he expects his men to be, encouraging and solicitous of their well-being, but also tough with discipline, and cautious and very thorough in preparation for and execution of battle. (in Campbell, 87)

Corbulo was made governor of Cappadocia and Galatia, and given the task of securing both Syria and the small kingdom south of Armenia, Sophene (Dsopk) to beef up Rome's presence in the region and remind Parthia who they were up against. The general, famed as a strict disciplinarian, also reorganised the Roman army in the east - clearly, he was preparing for a significant campaign. The precautions taken before an outright battle with Parthia may well have been because the last time the two sides had fought, at the battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, the Romans had suffered a disastrous defeat and their commander Marcus Licinius Crassus had lost his head as well as his army.

The Romans, then, were all too familiar with the Parthian strategy of avoiding close combat and relying on their skill as horse-riders able to fire their bows even behind them while still on the move - the famous “Parthian shot”. The Roman army's strength was a full-on battle of large set-pieces where discipline and teamwork made the manoeuvres of the legions a formidable weapon in itself. The Parthians, though, favoured a more mobile approach to warfare with the use of feigned retreats to lull their enemy into a disordered pursuit. As a result, the campaign for control of Armenia was never going to be a short one.

When Parthia declared Armenia a vassal state in 58 CE, Corbulo moved northwards and attacked Armenia itself. If the Roman general could not pin down the enemy on the battlefield he could at least attack stationary targets like cities and fortresses. By the time the Romans arrived in Tiridates' kingdom, Vologases had been forced to withdraw to deal with internal troubles in Parthia, but Tiridates remained at the Armenian capital of Artaxata (Artashat). Tiridates was actually supported by most of the Armenian people who were more sympathetic to Parthia than to Rome for historical and cultural reasons.

Corbulo proved again to be a very capable field commander and with logistical support from Roman ships at Trebizond and other ports on the Black Sea, he took and destroyed Artaxata. Corbulo's strategy was clearly to cause as much terror as possible in the Armenian people and so dissuade them from assisting Parthia or resisting Roman force. Indeed, such was Corbulo's reputation for taking and destroying forts and settlements that the inhabitants of Artaxata opened the city gates and surrendered without a fight. It is also worth noting that the commander first let the non-combatants flee the city before he torched it, a decision based on the belief that he did not have a sufficient force to hold the city and continue the campaign at the same time.

Tigranocerta, the second most important fortress city, soon fell to the Romans in similar circumstances:

Soon afterwards, Corbulo's envoys whom he had sent to Tigranocerta, reported that the city walls were open, and the inhabitants awaiting orders. They also handed him a gift denoting friendship, a golden crown, which he acknowledged in complimentary language. Nothing was done to humiliate the city, that remaining uninjured it might continue to yield a more cheerful obedience. (Tacitus, Annals, Bk. 14:24)

With these successes and others, by 60 CE, Corbulo could claim to rule over all of the Kingdom of Armenia and Tiridates was forced to flee back to his brother in Parthia. In the same year, Tigranes V (r. c. 60-61 CE), who had impressive royal connections being the grandson of Herod the Great, was set on the throne as a pro-Roman monarch. Corbulo, meanwhile, was made governor of Syria, but the job was not yet finished.

Tigranes V's cameo reign came to an abrupt end when the Parthians sent an army to besiege him in Tigranocerta. In 62 CE at Rhandia a joint Armenia-Parthia army with its famous mailed cavalry and horse archers won a victory against a Roman army which, significantly perhaps, was no longer commanded by Corbulo but the rather less accomplished Caesennius Paetus. Paetus, inadequately defending his winter army camp and regularly tempted into forays which overstretched his supply lines, capitulated to the Parthians on disgraceful terms and was dismissed for his troubles by Nero.

In 63 CE Corbulo, now responsible for all of Cappadocia-Galatia and Syria, was given maius imperium or supreme command in war. He was to return to Armenia to rescue and restore the standards of the legions under the command of Paetus and Roman ambitions in general in the region:

Corbulo, perfectly fearless, left half his army in Syria to retain the forts built on the Euphrates, and taking the nearest route, which also was not deficient in supplies, marched through the country of Commagene, then through Cappadocia, and thence into Armenia. Beside the other usual accompaniments of war, his army was followed by a great number of camels laden with corn, to keep off famine as well as the enemy. (Ibid, Bk. 15:12)

With his objective achieved, Paetus' beleaguered troops were sent back to Syria to recuperate while Corbulo prepared for one final offensive in Armenia. The commander,

...led thence into Armenia the third and sixth legions, troops in thorough efficiency, and trained by frequent and successful service. And he added to his army the fifth legion, which, having been quartered in Pontus, had known nothing of disaster, with men of the fifteenth, lately brought up, and picked veterans from Illyricum and Egypt, and all the allied cavalry and infantry, and the auxiliaries of the tributary princes, which had been concentrated at Melitene, where he was preparing to cross the Euphrates. (Ibid, Bk. 15:26)

The threat of Corbulo once again in the field was sufficient for the Parthians to withdraw, and the Treaty of Rhandia was drawn up (named after the site in western Armenia). It was now agreed that Parthia had the right to nominate Armenian kings, Rome the right to crown them, and both powers would rule equally over Armenia with the king as their representative. Nero was thus given the privilege of crowning Tiridates in Rome in a lavish spectacle that did much to show the power and global reach of the Roman Empire.

Aftermath

In 66 CE Tiridates travelled to the great city of Rome to receive his crown from Nero in one of the most extravagant public spectacles the Eternal City had ever witnessed. Corbulo, on the other hand, was suspected of treason - or more precisely his son-in-law was - and invited to commit suicide in October of the same year. It was a strange twist of fate that the victor and loser on the battlefield would see such a complete turnaround in their fortunes. Before he died, Corbulo wrote an account of the conflict, his commentarii, which formed the basis for later writers such as Tacitus. Corbulo's prestige in the army never wavered despite his political downfall, which perhaps explains emperor Vespasian's (r. 69-79 CE) motivation for arranging a marriage between his son Domitian (r. 81-96 CE)and Corbulo's daughter Domitia Longina.

The wars against Parthia had been costly for the Romans, as is indicated by the reduction in the percentage of gold and silver in Roman coins of the period. The rivalry and disputes between Parthia and Rome would not go away either, and the two empires continued to clash until the early 3rd century CE.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.