The relationship between the Byzantine Empire and ancient Armenia was a constant and varied one with an equal mix of wars, occupations, treaties of friendship, mutual military aid, and cultural exchange. Regarded as a vital defence to the Empire's eastern frontiers, emperors used various means of influence from outright takeover to gifts of titles and lands to Armenian nobles. Influence went in the other direction, too, with several important Byzantine emperors being of Armenian descent, as well as many individuals who held key military and administrative positions in Constantinople and beyond.

Sources

There are several difficulties in assessing the relations between Byzantium and ancient Armenia. Aside from the usual problem of ancient historical sources having an inherent bias towards rulers, noble families, and high politics, account must be taken of the shifting geographical location of Armenia over the centuries and its regular division and redivision by successive empires in the region. There are problems, too, with primary sources which can be coloured by nationalism and left incomplete with deliberate omissions. There are also long silences in the historical record, notably from 730 to 850 CE and 925 to 980 CE. Nevertheless, a reasonable picture of relations between the two states can be drawn and the historian T. W. Greenwood, by way of a summary, highlights three stand-out features of this relationship:

In the first place, relation were continuous…Secondly, they were multi-layered…it seems very likely that lesser lords and individual bishops were also in contact with Byzantium throughout…Thirdly, they were reciprocal. Byzantium was eager to secure its eastern flank and therefore sought to attract Armenian clients into its service. At the same time Armenian princes looked to Byzantium to bolster their own status within Armenia through the concession of titles, gifts and money…It is no coincidence that the Byzantine army - and then the state - came to be filled with men of Armenian origin or descent. (Shepard, 363-4)

A Strategic Position

Ancient Armenia, because of its geographical location and strategic importance in controlling access to Mesopotamia from Asia Minor (and vice versa), had long been a coveted chunk of territory for the empires who dominated the region at any particular time. Whoever controlled the Armenian plain of Ararat could then launch an army to attack either east or west. This situation had not changed by the 4th century CE and the rise of the Byzantine Empire with its capital at Constantinople. Byzantium's first opponent and territorial rival was the Sassanid Empire in Persia (224-651 CE). From 252 CE the Sasanids became more ambitious to rule directly over Armenia and made attacks on several cities. Byzantium, defending the status quo, opposed such incursions.

There followed a century of wrangling over control of Armenia, which came to the boil when Shapur II, the Sasanid ruler (r. 309-379 CE), attacked Armenia in 368 and 369 CE, destroying several cities. A decade later, emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) and Shapur III (r. 383-388 CE) agreed to formally divide Armenia between the Byzantine Empire and Sasanid Persia. Henceforth, the Roman-controlled part of Armenia now largely fades from the historical view with only sporadic returns whenever it suited Byzantine historians.

Persian Armenia

To clarify Byzantium's relationship with their part of Armenia, it is perhaps useful to first look over the diplomatic fence at the Persian side. Persia installed marzpan (viceroy) rulers in their half of the country (Persarmenia) from 428 CE in a system that would endure until c. 651 CE. Representing the Sasanian king, the marzpan had full civilian and military authority. There had been rumblings of discontent amongst the Armenian nobility and clergy following Persian cultural imperialism, but matters really came to a head with the succession of the Persian king Yazdgird (Yazdagerd) II in c. 439 CE. Sasanid rulers had long been suspicious that Armenian Christians were all simply spies of Byzantium, but Yazdgird was a zealous proponent of Zoroastrianism, and the double-edged sword of political and religious policy was intended to cut Armenia down to size.

In May or June 451 CE at the Battle of Avarayr (Avarair) in modern Iran, the Armenians rebelled against oppression and faced a massive Persian army. The 6,000 or so Armenians were led by Vardan Mamikonian, but unfortunately for them, help from the Christian Byzantine Empire was not forthcoming despite an embassy sent for that purpose. Perhaps not unexpectedly, the Persian-backed marzpan, Vasak Siuni, was nowhere to be seen in the battle either. The Persians, greatly outnumbering their opponents and fielding an elite corps of “Immortals” and a host of war elephants, won the battle easily enough and massacred their opponents; 'martyred' would be the term used by the Armenian Church thereafter. Indeed, the battle became a symbol of resistance with Vardan, who died on the battlefield, even being made a saint.

Byzantine Armenia

Meanwhile, from 387 CE, the Byzantines had divided their portion of Armenia into two areas: Armenia I in the north and Armenia II in the south. Each area had a governor (praeses) who was in turn responsible to the governor (vicar) of the imperial administrative district or diocese of Pontus, who was himself responsible to the Praetorian Prefect of the East. Aside from paying taxes and performing military service for Byzantium, the control from Constantinople was light, although one legion and extra cavalry units were permanently stationed in each area. The bureaucracy of the empire in the two regions was filled with members of the Armenian nobility but, at least administratively, Armenia was fully absorbed into the Byzantine Empire.

From the 5th century CE, some cities were especially prosperous, notably Artashat, which became an important trading point between the Byzantine and Persian Empires. In 536 CE, when the Byzantine emperor Justinian I reorganised the administration of the region, Armenia was split into four areas or provinces (Armenia I- IV), each with its own capital. Byzantine laws began to be embedded more deeply into Armenian society, too, especially in such areas as inheritance. Previously, Armenian nobles had passed on their land to their sons (or brother if they had none) with daughters being ineligible to inherit. Justinian changed this so that women could legally inherit their parent's property. Rather than a move for women's rights, the change in law was designed to weaken the stranglehold of traditional Armenian clans on landed estates as now women could pass on the family property to their husbands who could be outside the clan structure or even foreigners. There was resistance to the changes from some clans - the governor of Armenia I was murdered in one uprising in 538 CE - but ultimately they did not have the political power to prevent them and those who continued to resist were deported, especially to the Balkans.

Artashat's continued prosperity is evidenced by an edict of 562 CE which confirmed the city as one of only three official trading points between the Byzantine and Persian Empires. A customs post there was overseen by officials known as “commercial counts” or comites commercium. By the end of the 6th century CE Armenia was again a point of dispute between Persia and the Byzantine Empire, and so a redivision was drawn up in 591 CE, which saw Byzantium acquire two-thirds of Armenia. Under the new agreement, the important city and former capital of Dvin became a frontier city between the two spheres of influence and, as a result, disputed territory. Inside Armenia, too, there was a split amongst the nobility as some clans supported Persia (e.g. the Bagratuni) while others favoured Byzantium (e.g. the Mamikonians).

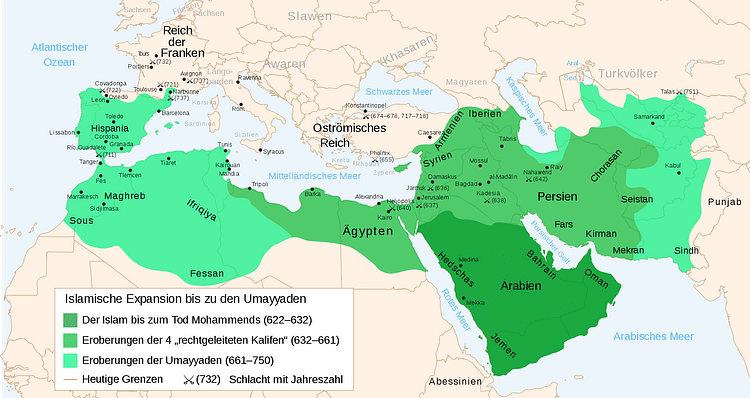

A Byzantine army of emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE) attacked Dvin in 623 CE. Worse was soon to come, though. In 627 CE a full-scale war against the Sasanids was carried out by Heraclius and Armenia was caught in the crossfire. This campaign ended the Sassanid control of Armenia but Byzantine rule was to be short-lived following the dramatic rise of a new power in the region, the Arab Umayyad Caliphate, which conquered the Sasanid capital Ctesiphon in 637 CE. Armenia was conquered by the Arabs from Damascus from 640 CE. The Byzantine emperors had not given up on Armenia, and in 642 CE, Constans II (641-668 CE) attacked Dvin but without success. By 701 CE, after decades of playing, as so often before, the role of strategic pawn in a battle of Empires between the Arabs and the Byzantine Empire, Armenia was made a province of the Umayyad Caliphate.

Manzikert & the Umayyad Caliphate

Byzantine emperor Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) attacked Armenia between 746 and 752 CE, taking advantage of the civil war which preoccupied the Umayyad Caliphate. The Byzantine Empire would assert even more influence over Armenia from the 10th century CE. Notable events include the Byzantines helping the Bagratuni establish their kingdom in 914 CE, the invasion of emperor John I Tzimiskes (r. 969-976 CE) in 974 CE, the annexation of the province of Tayk in 1000 CE, the capture of the Armenian capital Ani and fall of the Bagratuni kingdom in 1074 CE, and the seizure of Kars in 1065 CE.

In August 1071 CE there was the momentous Battle of Manzikert. Fought north of Lake Van on Armenian soil between the armies of the Byzantine Empire and Seljuk Turks (a nomadic tribe of the Asian steppe), the battle was one of the worst defeats the Byzantines had ever suffered, if not in numbers then at least in terms of psychology. The victorious Seljuk army captured the Byzantine emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (r. 1068-1071 CE), and, with the empire in disarray as generals squabbled for the throne, nothing could stop them sweeping across Asia Minor. The Byzantine Empire would go on for a few more centuries yet but Manzikert is seen by many historians as the beginning of a long and seemingly unstoppable decline.

Throughout the 12 century CE, Armenia and Byzantium squabbled over the Cilician plain and its various cities. Several Crusader armies passed through Armenia, and then another group of unwanted visitors, this time even more ruthlessly destructive ones, ravaged the region: the Mongols, who attacked in 1236 CE and caused a mass-migration of Armenians to Russia and the Crimea.

Armenian Byzantine Emperors

There were several notable Byzantine emperors actually of Armenian descent as the dynasties of Constantinople came and went with usurpers grabbing their opportunities to oust the incumbent emperor. This was particularly so from the 9th century CE when military threats to the empire ensured that an emperor could be deposed if he proved incapable on the battlefield. One such figure was Leo V the Armenian, who ruled in Constantinople from 813 to 820 CE. Of humble origins, Leo rose the ranks of the Byzantine army to eventually become the strategos or military governor of the province of Anatolikon, the most important region of Asia Minor. When the Bulgar army looked set to attack Constantinople in June 813 CE, the reigning and incompetent emperor Michael I Rangabe (r. 811-813 CE) was ousted and the people looked to Leo to save the day. Paying off the Bulgars with a huge ransom in gold, Leo V did indeed save the city. His glory was short-lived, for just seven years later the emperor lost his throne to his former friend and ally Michael II (r. 820-829 CE) in one of those typical episodes of violence which plagued Byzantine politics. Murdered in church, Leo's body was dragged around the Hippodrome of Constantinople for the public to scorn and ridicule.

Perhaps the most famous Armenian emperor, or more correctly, infamous, was Basil I (r. 867-886 CE). Basil was an Armenian peasant, who, through his friendship with the emperor Michael III (r. 842-867 CE) rose to prominence at court. Basil was ambitious, though, and he murdered his benefactor to take the throne for himself in 867 CE. Strengthening and modernising the Byzantine navy, Basil's reign saw several notable victories and expansion in the Mediterranean and Asia Minor. Basil also embarked on a massive rebuilding programme in Constantinople and a major overhaul of Byzantine law. His reign would later be regarded as a Golden era, but the emperor lost his throne just as violently as he had gained it - murder disguised as an unlikely hunting accident probably arranged by his successor, Leo VI (r. 886-912 CE).

A third notable Armenian on the Byzantine throne was Romanos I Lekapenos (r. 920-944 CE). Another successful emperor, he, like Leo V, had risen through the military ranks to become commander of the imperial fleet in 912 CE. Also like Leo, Romanos took the throne by force after the Bulgars proved the undoing of his predecessors. Easing his way into palace affairs, Romanos first made himself regent for the young Constantine VII in 919 CE and then, declaring himself emperor one year later, he married his daughter to the legitimate emperor for good measure. Once in power, Romanos proved worthy of the position and he reconciled the various factions of the Byzantine Church, made significant land reforms to protect poorer farmers, there was a peace brokered with the Bulgars and, with the gifted general John Kourkouas leading the army, significant victories in Asia Minor against the Arabs. The Rus Vikings did attack Constantinople in 941 CE but the city's Theodosian Walls did their job, and the raiders were repelled. When Romanos died, the throne was returned to the legitimate line but, once again, he had shown that foreigners could rule just as well or badly as those emperors of true Byzantine descent.

Armenian-Byzantine Church Relations

Another area, besides politics, rulers, and administrators, which connected Byzantium and Armenia was religion. Armenia's zeal for Christianity, the religion being officially adopted around 314 CE, did bring it closer to the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople being the head of the Christian church in the East. However, the Armenian and Byzantine churches did often differ on matters of dogma. Disagreement with the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE opened a rift which would never be closed. Then the Council of Dvin c. 554 CE declared the Armenian Church's adherence to the doctrine of monophysitism (that Christ has one nature and not two) thus breaking away from the duophysitism of the Roman Church. As in politics, Armenian Christians were having to find their own rocky road between East and West as the Armenian church broke away from Constantinople in the mid-7th century CE.

Cultural Exchange

From the 6th century CE, Armenians relocated to many other parts of the Byzantine Empire and especially Constantinople. They were perhaps the most assimilated of any ethnic group, although they maintained their own language, literature, art, and religious practices. Armenian traders, scholars, military personnel of all ranks, and mercenaries became part and parcel of Byzantine everyday life.

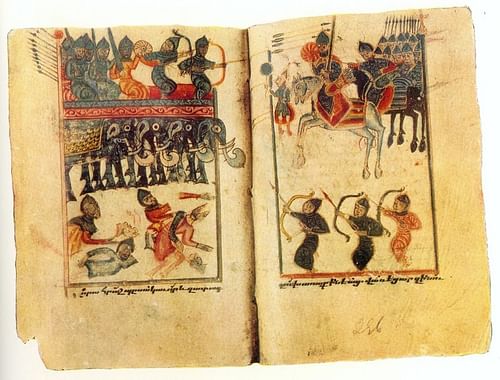

Where cultural innovations originally spring from is always difficult to pinpoint with accuracy, but some scholars claim that ideas in architecture and illuminated manuscripts, for example, came to Byzantium from Armenia. Indeed, the architect who famously repaired the dome of the Hagia Sophia church in Constantinople after the 989 CE earthquake, one Trdat of Ani, was an Armenian. Undoubtedly, features of Byzantine architecture (e.g. Greek monograms, eagle capitals, and classicising Ionic columns) travelled in the other direction, too. Ideas in art, too, were exchanged and travelled via the manufactured goods which were traded between the two powers such as those made in Armenia (textiles, glazed pottery, glassware, and metalwork) and those made in Constantinople or imported there from around the world by land and sea.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.