Cynic philosopher, wife of Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360 – 280 BCE), and mother of his children, Hipparchia of Maroneia (l. c. 350 – 280 BCE) defied social norms in order to live her beliefs. She is all the more impressive in that she taught and wrote in Athens where women were considered second-class citizens.

Hipparchia was from the rich northern city of Maroneia, famous for its wine production and a profitable trade center. She came from a wealthy family, most likely involved in making or selling wine, but gave up her privileged position to marry the penniless Crates, a Cynic philosopher, and adopt his lifestyle of Cynic poverty. She lived with him on the streets of Athens, bore him two children whom she raised while also teaching, writing, and presumably traveling, and is thought to have taken over the responsibilities of the school he founded after his death.

She is said to have married Crates when she was young, and he was significantly older and so she most likely also cared for him when his health began to fail prior to dying of natural causes. Her achievements would be impressive for anyone at any time in history, but Hipparchia shines all the more brightly because of the society in which she lived which did not hold women in very high regard.

Women in ancient Athens primarily served men in the home as wives or at festivals and parties as prostitutes, while as daughters, they were pawns to be played in acquiring wealth and prestige through marriage. Hipparchia of Maroneia turned this entire paradigm upside down, but, unfortunately, her example would not be followed by Athenian women of her age.

Ancient Greek Women

Women in ancient Greece, outside of Sparta, held a social position just a little above slaves. They had no political or legal voice, and their identities were completely defined by the males in their lives, first their fathers, then husbands, and then sons. Scholar and historian Helena P. Schrader notes:

The near complete absence of Greek women in ancient history (as opposed to Greek mythology and drama) is a function of the fact that ancient historians were predominantly Athenian males from the classical or Hellenistic periods. Athenians of these periods did not think women should be seen – much less heard – in public. Women had no public role and so no business in politics or history. As Pericles said in one of his most famous speeches, "The greatest glory of a woman is to be least talked about, whether they are praising you or criticizing you" (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 2:46). (Schrader, 1)

It is a telling detail that even in Sparta, where women were considered the near-equals of men and often exerted considerable control over them publicly, the dates of Gorgo of Sparta are unknown, and she is defined in history as the wife of the famous king Leonidas (r. 490-480 BCE), hero of the Battle of Thermopylae. Sparta was the most progressive of the Greek city-states as far as women’s rights and status were concerned, and yet not even here can be found even the dates of one of the most famous queens. Gorgo is regularly dated as the daughter of King Cleomenes (r. 520-490 BCE) or the wife of Leonidas. Scholar Thomas Cahill comments on how women were viewed generally in the Greek city-states and specifically in Athens:

Girls of good families…begin as presexual beings, are tamed by conjugal penetration, and forthwith settle down to the work that is properly theirs – keeping the man’s house and raising his children. There is no true ideal for the Greek woman, no naked eternality, only the tasks of becoming: preparation, marriage, childbirth, childrearing, suffering society’s toleration if she survives past menopause, death. (216)

Although goddesses frequently played important roles in Greek religion and Athens itself claimed the goddess Athena as its patron deity, women in daily life were denied any participation in their status. Educating a girl in Athens was considered a complete waste of time because she would never be given the opportunity to make any use of it.

Girls were reared by their mothers to learn "women’s work" which was entirely focused on running a household for a male. Girls were married off to much older men to formalize business deals or add lands and wealth to the family of the bridegroom and could not even sue for divorce or represent themselves in court unless they were a metic (foreign-born). The consort of Pericles of Athens (l. 495-429 BCE), Aspasia of Miletus (l. c. 470-410/400 BCE), is a notable exception to the overall invisibility of Athenian women, and this is most likely because she was a metic.

The Cynic School & Crates

Maroneia was no more progressive in women’s rights than Athens and girls there were brought up according to the same policies. The philosophical schools which began to flourish throughout Greece after the Milesian School of Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) were closed to women. Even though Socrates (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE) seems to have thought highly of women, even – according to Plato – crediting the woman Diotima with teaching him the meaning of true love – he had no female students.

Plato (l. c. 438/427-348/347 BCE) had none either, and there are none recorded in any of the schools founded by Socrates’ students except for Arete, the daughter of the hedonist philosopher Aristippus of Cyrene (l. c. 435-356 BCE) who not only ran the Cyrenaic School after her father’s death but instructed her son, Aristippus the Younger, in her father’s vision.

The Cyrenaic School taught that pleasure was life’s greatest goal and pursuit of pleasure its ultimate meaning. To fully experience and enjoy existence, Aristippus taught, one must educate one’s self in what was truly good and what was an irritating waste of time and then devote one’s self to the former. Pleasures were to be enjoyed as long as one did not allow one’s self to be controlled by them. One could drink as much wine as one liked, for example, as long as one could honestly do without it.

Aristippus’ vision was challenged by the schools founded by the other students of Socrates, but perhaps most significantly by the Cynic School founded by Antisthenes of Athens (l. c. 445-365 BCE) who advocated for living simply and without any kind of ornamentation in one’s life in order to experience reality as its fullest. The Cynics were so-called because people believed they lived like dogs, owning nothing and pursuing their own interests, and called them by the Greek name for "dog" (kynos) translated as "cynic", which today is understood as one who is skeptical; a definition which comes from the school that questioned all social conventions. Antisthenes preached a doctrine of austerity in the extreme through which one could be free by renouncing all the trappings of society and conventional value, including one’s possessions and position, and living without any obligations to anyone.

Antisthenes’ most famous student was Diogenes of Sinope (l. c. 404 – 323 BCE) who is best known for holding a lantern or candle up to people’s faces in broad daylight on the streets of Athens saying he was searching for an honest man. By "honest" he meant "real", as in someone who was not just playing the part they had accepted from their parents and society, someone who was a true human being living according to their own understanding of the world and their place in it. Diogenes influenced a number of the young men of Athens and especially one who had traveled there specifically to study philosophy and become the kind of man Diogenes was looking for: Crates of Thebes.

Crates instantly took to Diogenes’ vision and lived it as fully as his master. While Diogenes could be somewhat abrasive and off-putting, though, Crates was gentle and welcoming. He would frequently enter people’s houses uninvited and unannounced when he heard someone there needed advice or consolation and his cheerful personality made him welcome wherever he went. After he helped the young philosopher Metrocles of Maroneia out with a problem, Metrocles introduced him to his sister, Hipparchia, who fell in love with the older philosopher.

Hipparchia as Wife & Mother

According to the historian Diogenes Laertius, Hipparchia would not consider any of the many suitors for her hand, rejecting all and threatening suicide unless her parents would consent to her marriage to Crates:

She fell in love with the discourses and the life of Crates and would not pay attention to any of her suitors, their wealth, their high birth, or their beauty. But to her, Crates was everything. She used even to threaten her parents that she would make away with herself unless she were given in marriage to him. Crates therefore was implored by her parents to dissuade the girl, and did all he could, and at last, failing to persuade her, got up, took off his clothes before her face, and said, "This is the bridegroom, here are his possessions: make your choice accordingly; for you will be no helpmeet of mine unless you share my pursuits." The girl chose and, adopting the same dress, went about with her husband and lived with him in public and went out to dinners with him. (Book VI. Ch. 7, 96-97)

Hipparchia devoted herself to Crates by fully embracing his philosophy. All of the extant reports of her life strongly suggest she was drawn to Crates because she recognized him as a truly honest man without pretense or the layers of trappings society controlled people through. There were few options open to a woman in ancient Greece who chose anything other than marriage, entertainment, or prostitution, and, in Crates, Hipparchia recognized an opportunity to live as she wanted to outside of societal dictates even though there seems no doubt she was genuinely attracted to him and he to her.

All of the works about her come from long after she died, and many are suspect as more legendary than factual, but it is said that, at one point, she was criticized by Crates for weaving him a cloak because he questioned whether it was done from a pure motive of caring or because she wanted to be seen by others as a good wife performing her traditional role of caring for her husband. This story, given in The Cynic Epistles (1st century CE), may not be historically accurate but is thought to have been passed down by oral tradition by followers of the couple and underscores Hipparchia’s devotion to her husband in that she would risk his censure to provide him with some warm clothing.

In the same way, she is depicted as a dutiful mother who took care of herself during her first pregnancy and delivered her son, Pasicles, without any trouble owing to her Cynic discipline. She is said to have raised him as well as her daughter (name unknown) according to Cynic beliefs. Simplicity of life was understood as true life and so, instead of an expensive possession like a cradle, Pasicles is said to have been rocked to sleep in a large tortoiseshell, bathed in cold water to enliven his spirit, and given only enough food to satisfy and nourish but not enough to encourage luxury or dissipation of the spirit. Although no accounts mention how her daughter was raised, it is assumed that Hipparchia maintained the same discipline and policy.

Hipparchia the Philosopher

Hipparchia is said to have written a number of discourses, treatises, and letters but none of these have survived. Scholar Joyce E. Salisbury describes her life with her husband:

Hipparchia lived the simple life of a cynic, dressing in the same rough clothes as Crates and engaging in the public discourse of philosophers…Hipparchia joined Crates at public dinners, shocking Greek men who expected only prostitutes to appear at these gatherings. (159)

The two main sources for information on Hipparchia’s life – the Lives of Eminent Philosophers by Diogenes Laertius (3rd century CE) and the Suda (10th century CE) both provide the best-known stories of Hipparchia’s philosophical and public life. Both stories have to do with her professional – and seemingly antagonistic – relationship with the Cyrenaic philosopher Theodorus the Atheist (l. c. 340 - c. 250 BCE) who, like his mentor Aristippus the Younger, advocated pleasure as the ultimate goal in life and, like the elder Aristippus, charged students to attend his lectures. He also claimed and taught that education went hand-in-hand with the pursuit of pleasure in that one needed to be educated to recognize what was worth pursuing in life.

Hipparchia is said to have written many letters to Theodorus which are assumed to be arguments against his claims as well as his practice of charging a fee for his knowledge. The contents of these letters are unknown, but the two episodes concerning Hipparchia and Theodorus in public strongly suggest that the letters were a series of philosophical arguments and refutations of each other’s beliefs. Salisbury gives the Suda’s version of Laertius’ account of a dinner party at which Theodorus tried to embarrass and shame Hipparchia:

[At this dinner, Hipparchia] "confounded" one of her critics, Theodorus, by offering arguments in a philosophic style: "If it is not wrong for Theodorus to do a particular act, then it is not wrong for Hipparchia to do it. Further, if Theodorus slaps himself, he does nothing wrong, therefore, if Hipparchia slaps Theodorus, she does nothing wrong either." The logic of the second statement, though questionable, had Theodorus stumped. At a loss as to what to do, he tried to embarrass Hipparchia by crudely pulling up her cloak. She refused to be bullied and, according to [the Suda], "did not panic like a woman". (159)

Later, at this same party (it would seem) Theodorus decided to remind everyone in attendance that Hipparchia was a woman and, as such, should be at home concerning herself with "women’s work" such as weaving. Diogenes Laertius reports that Theodorus cried out, "Is this the woman who left her carding combs beside the loom?" in reference to the woman’s traditional role as a weaver. Hipparchia is said to have responded, "It is I, Theodorus – but do you suppose that I have been ill-advised about myself if, instead of wasting further time upon the loom, I spent it in education?" (Book VI, ch. 7, 98). Theodorus had no response to this as he could not answer without either contradicting his own teachings regarding the importance of education or admitting that women should be educated as well as men.

Besides these two anecdotes, a few references by other writers, and an epigram preserved by the Roman poet Antipater of Sidon (l. 2nd century CE), nothing is known of Hipparchia of Maroneia but even these references are enough to suggest that she was highly regarded and, no doubt, controversial in her own time and for many centuries afterwards. Simply the fact that Diogenes Laertius includes her in his Lives of Eminent Philosophers in the 3rd century CE speaks loudly to how her legacy endured.

Conclusion

If Hipparchia’s death date is accurate at 280 BCE, then she would have only led the Cynic School at Athens for a few months after Crates’ death and, afterwards, the school reverted back to male leadership. In the present day, scholars and writers have tried to make Hipparchia a model of proto-feminism, claiming that her example inspired other women to break from societal roles and live their own lives in ancient times. Joyce E. Salisbury makes the very admirable attempt at this claim, writing:

While much of her intellectual heritage has been lost, her life remains an example of many of the trends characteristic of the Hellenistic world. In the larger, impersonal world of cosmopolitan cities, family ties broke down, and some young men and women began to choose their own partners for love instead of practical alliances. Many also rejected the traditional religion and morality to find personal fulfillment as Hipparchia and Crates did, following philosophy and defying conventions. In making their own path, people like this couple opened the choices available to individuals in the West. (159-160)

Although there is certainly a measure of truth in Salisbury’s claims, unfortunately, Hipparchia’s example did not inspire the liberation of women in Athens or elsewhere in ancient Greece. Ancient Athens is routinely hailed as the "birthplace of democracy", but it never recognized the rights, feelings, or aspirations of half its population. Women like Aspasia and Hipparchia and a very few others stand out in history precisely because the recognition of their individuality and accomplishments is so rare.

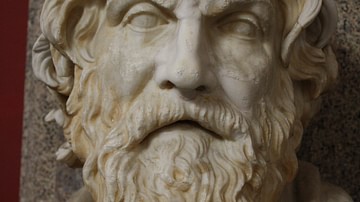

![Crates of Thebes [Painting]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/2913.jpg?v=1732987687)