The Great Palace of Constantinople was the magnificent residence of Byzantine emperors and their court officials which included a golden throne room with wondrous mechanical devices, reception halls, chapels, treasury, and gardens. In use from 330 to 1453 CE, it was sumptuously decorated throughout with exotic marble and fine mosaics to impress visitors from near or far with the wealth and power of the Byzantine Empire.

Construction & Layout

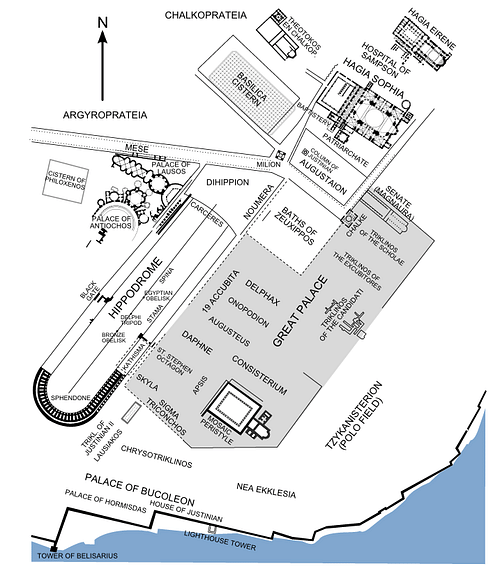

The Great Palace was first constructed by emperor Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) on an elevated part of the city and then added to by his successors until it became something of a sprawling and eclectic magnificence. Located just east of the city's Hippodrome, the palace occupied a rectangular space against the sea walls of the city to the south-east and the forum and Hagia Sophia church to the immediate north-east. A residential wing, the Palace of Daphne, connected the palace to the city's famous circus so that emperors could easily and safely attend the public spectacles held there. Over the centuries the complex would include:

- a magnificent throne room

- halls for official audiences, state banquets, and coronations

- various reception rooms

- several churches and chapels

- a university

- Roman baths

- a grand library where new manuscripts were also produced

- sleeping quarters for the royal family and their entourage

- the Pharos signal tower

- a barracks for the royal guards

- gardens with terraces and fountains

- a polo field

- many examples of fine art, especially mosaics and statues.

Many of these buildings and features, constructed over different centuries, were connected by corridors and covered collonaded walkways. The whole complex was surrounded by a wall during the reign of Justinian II (r. 685-711 CE).

The general layout and key elements are possible to reconstruct from such descriptions as found in Constantine VII's De ceremoniis (On the Ceremonies of the Byzantine Court), written in the 10th century CE. Unfortunately, modern archaeological excavations at the site have been unable to add many details on specific buildings within the palace complex as it was completely built over by the Ottomans.

Key Buildings

The palace's main entrance was the monumental Chalke Gate which was used for ceremonial processions such as triumphs. It had gigantic bronze doors, perhaps explaining its name 'brazen' or chalke. The version built by Justinian I (r. 527-656 CE) had four arches supporting a dome and covered colonnade. The interior of the dome was decorated with a glittering mosaic depicting the emperor and his empress Theodora along with a select group of senators. Justinian's victories over the Goths and Vandals were also shown. The exterior of the gate carried statues of such figures as past Byzantine emperors, Justinian's foremost general Belisarius, Greek philosophers, and four Gorgons. Most splendid of all was the biggest icon in Constantinople, a gilded representation of Jesus Christ known as Christ Chalkites.

The Chrysotriklinos, built by Justin II (r. 565-574 CE) was the main audience hall which was resplendent in gold decorations, hence its name which means "Golden Hall". Used as the principal reception room, the emperor had a throne in the apse and fine chairs were set out for visitors. To make sure such visitors were left in no doubt as to the emperor's power and wealth there was a huge cabinet, the pentapyrgion, which was filled with treasures from across the empire. The hall had eight vaulted niches which led to other rooms, 18 windows, and a massive domed ceiling.

The Great Palace also functioned as a huge treasure store and not just of gold, silver, gemstones, and war booty but also of priceless religious artefacts. The most revered were the relics related to Christ's crucifixion which were held in the chapel of the Virgin of the Pharos. Another priceless artefact was the Mandylion icon. This was a shroud thought to be imprinted with an impression of the face of Jesus Christ in the now classic pose known as the Pantokrator which is seen today in churches worldwide. The shroud was taken to France by Crusader knights but then lost during the French Revolution.

The Purple Room

Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) added a particularly long-lasting and important feature to the palace. The emperor had seven children in all, and the birth of his first, his son Leo, would give rise to the oft-used expression, “to be born in the purple” or porphyrogennetos. The phrase derived from the porphyry, a rare purple-laced marble, that was used in a chamber of the palace where Leo's birth, and many subsequent royal ones, took place. The restriction that only royalty wore robes made with the expensive Tyrian purple dye dated back to Roman times, and this new tradition was one more attempt to further reinforce the legitimacy of dynastic succession and deter would-be usurpers.

Restoration of Theophilos

Emperor Theophilos (r. 829-842 CE) is credited with a lavish restoration of the royal palace and its gardens, which, over the centuries, had become something of a hotchpotch architectural mess. Buildings were ripped down and new homogenous ones with connecting corridors were built using white marble, fine wall mosaics, and columns in rose and porphyry marble.

Best of all was the Magnaura. This building was a basilica with three aisles and galleries and was used as a reception room. To impress visitors, Theophilos commissioned the fiendishly inventive Leo the Mathematician to make a throne that could suddenly lift the emperor up to the height of the ceiling while automated golden organs blasted out music. The other wonders of this golden throne room are here described by the historian L. Brownworth:

No other place in the empire - or perhaps the world - dripped so extravagantly in gold or boasted so magnificent a display of wealth. Behind the massive golden throne were trees made of hammered gold and silver, complete with jewel-encrusted mechanical birds that would burst into song at the touch of a lever. Wound around the base of the tree were golden lions and griffins staring menacingly from beside each armrest, looking as if they could spring up at any moment. In what must have been a terrifying experience for unsuspecting ambassadors, the emperor would give a signal and a golden organ would play a deafening tune, the birds would sing, and the lions would twitch their tails and roar. (162)

The Tetraconch of Theophilos was another of the emperor's additions, a four-winged building whose floor plan formed a Greek cross. Then, a little later in the mid-9th century CE Caesar Bardas, the brother of Theodora, regent of Michael III (r. 842-867 CE), was responsible for establishing the famous university in the Magnaura, where one of the faculties was headed by Leo the Mathematician.

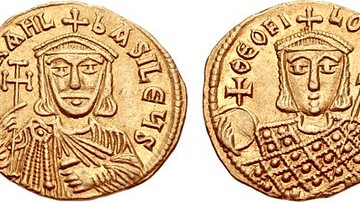

Basil I's Additions

The next notable addition was the Nea Ekklesia (New Church), built by Basil I (r. 867-886 CE) within the grounds of the palace. The church was magnificent with five gilded domes, exotic coloured marble, and gem-studded walls on the inside, silver decorations and archangels on the outside, two fine fountains and bells shipped in from Venice. Unfortunately for modern tourists, the church blew up in 1453 CE after the Turks had been using it as a gunpowder store.

Basil also built for himself a brand new palace within a palace, the Kainourgion. It had mosaic flooring depicting giant eagles, wall paintings, eight columns of green stone, and eight of onychite (a type of marble), and a throne room with a ceiling made from glass mosaic and solid gold filling. There was a half-dome at one end of this room with a giant painting of Basil and adoring generals presenting the emperor with a symbol from each city that his armies had conquered.

Attacks on the Palace

The Great Palace may have been the royal residence but this did not make it immune to damage from the people and sometimes even emperors themselves. The Chalke Gate was destroyed during the Nika Revolt of 532 CE when supporter factions of the Hippodrome went on the rampage fuelled by the general populace's displeasure at the heavy tax policies of emperor Justinian I. Brutally quashing the 11-day riot, Justinian then rebuilt the Chalke. The palace was not impregnable to assassins either, as shown by the small group who disguised themselves as monks and butchered Leo V the Armenian (r. 813-820 CE) while he was in one of the chapels on Christmas Day in 820 CE.

Emperor Leo III (r. 717-741 CE) was a staunch iconoclast, that is, he believed the worship of Christian images was idolatrous. Leo began his campaign of smashing icons with the biggest of them all, insisting that the golden image of Jesus Christ above the Chalke Gate be removed in 726 CE. A riot of protestors broke out, and rumblings of discontent could be heard everywhere from Italy to Greece, but it did not stop Leo on his wrecking mission. It would not be until the end of iconoclasm in 843 CE that the bishop of Constantinople, Methodios (r. 843-847 CE), commissioned the celebrated painter Lazaros to work on a new icon of Christ for the gate.

Later History

Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE) and his successors abandoned the Great Palace, choosing instead to reside in the sumptuous Blachernae Palace located in the north-west part of Constantinople which boasted up to 300 rooms and 20 chapels. The Great Palace continued to be used for state functions and receptions, though. From 1204 CE, following the sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, the Great Palace was used by the Latin emperors. It was during the sack of Constantinople that the chapels of the Great Palace were looted for their holy relics which were spirited away to churches in the west such as the chapel of Louis IX in Paris. From the reign of Michael VIII Palaiologos (1259-1282 CE) the palace went into further decline.

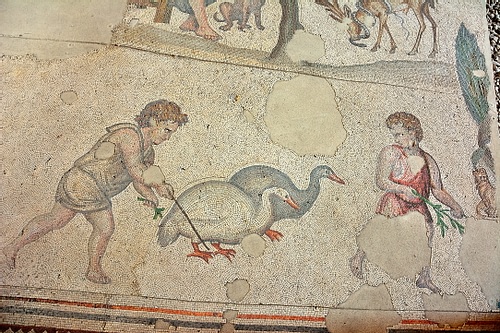

Not very much of the Great Palace's once fine buildings have survived but one of their common but most beautiful features has; the floor mosaics. Depicting all manner of scenes from Byzantine daily life but especially scenes of nature, hunting, and children playing games, the surviving mosaics mostly date to the 6th century CE, and they can be seen today in the Great Palace Mosaic Museum of Istanbul.