The genesis of Maya civilization in Mesoamerica was marked by an effervescence in the arts, the beginnings of their written language with glyphs, and a great attention to detail in the sphere of urban planning. Yet, despite these tremendous accomplishments, the Preclassic Maya (c. 1000 BCE - 250 CE) remain obscure and distant to many. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener, Communications Director at Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. James Doyle, Assistant Curator for Art of the Ancient Americas in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York about the finer aspects of early Maya civilization.

JBW: James, what was it that first prompted your interest in the Preclassic Maya? Did the early Maya always intrigue you for one reason or another?

JD: When I was growing up, I was always interested in the past and how societies work. This curiosity in global history led me to take anthropology my first year of college. The introductory course to archaeology happened to be taught by a Guatemalan archaeologist who was starting a field project at the site of Holmul the following summer. He was looking for volunteers, so I decided to go. Something about the art and architecture of the Maya captivated me, and I could make sense out of it even though it was far removed from anything I had learned before.

Over time, my interest grew in the broader anthropological question of why people in the past universally, though in very different times and places, built big things. Monumental architecture also implies two interrelated social phenomena: the cooperation of large groups of people and/or the leadership of an individual or a few. During the Preclassic period, people in the Maya Lowlands constructed some of the largest buildings in the region, so I focused on this time period for my dissertation work.

JBW: During this same period, the Olmec civilization (1200-300 BCE) reached its zenith. Their civilization was centered on the cities of San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Laguna de los Cerros in modern states of Veracruz and Tabasco, Mexico, which are located near several early Maya centers.

How did they affect and subsequently influence the Preclassic Maya city-states and kingdoms?

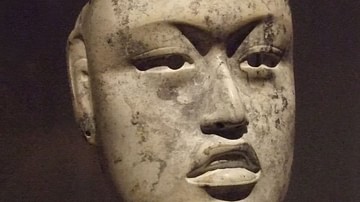

JD: It is clear that by around 1500 BCE, the Olmec peoples along the Gulf Coast were importing jadeite from the Motagua River Valley in southern Guatemala. San Lorenzo-era peoples probably would have interacted with the Maya folks in the area along this exchange route, but we really see much more evidence of interaction after about 1000 BCE, and especially after 800 BCE when La Venta becomes a major center. During this crucial time period, Preclassic Maya communities are beginning to create ceramic arts, they are also working jade into celtiform axes like we see at La Venta. The interaction of peoples throughout the region spread ideas and likely inspired the earliest monumental centers in the Maya Lowlands, such as the recently excavated site of Ceibal, Guatemala.

JBW: I think the general public would be surprised to learn that the Preclassic era was a time of tremendous innovation within Maya civilization. Some of the earliest examples of the Maya's complex writing system appeared by the 3rd century BCE, and it was also during the Preclassic era that the Maya first theorized the concept of zero.

James, why is it that so many of us are unaware of the sophistication and complexity of the Preclassic Maya? Additionally, what other achievements defined Preclassic Maya civilization?

JD: The great discoveries about the ancient Maya in the late 20th century CE, including major tombs, hieroglyphic decipherments, and mapping of new cities, mostly pertained to the Classic Period. What most people do not know is that the great Classic cities are almost always built on top of Preclassic Maya buildings and plazas. That is to say that much of what one sees on the surface is Classic or later construction. It takes a lot of excavation to reach Preclassic levels, and even when that happens, we have few (if any) readily identifiable royal tombs or flashy hieroglyphic histories that get publicized. The early Maya texts are not as easily decipherable, and as a result, scholarship in the Preclassic period was not as popular.

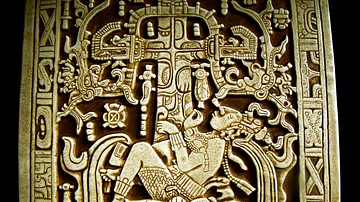

In the early 21st century CE, however, major Preclassic discoveries really changed the way even Maya specialists thought about the era before c. 250 CE. In addition to the writing system being very well developed at that time, major mural paintings seem to have been much more widespread than previously imagined. The site of San Bartolo, Guatemala, which is of relatively modest size in Preclassic terms, has the “Sistine Chapel” of the Preclassic Maya dating to 100 BCE: mythological narratives in vivid paintings that were carefully buried by people when they constructed a larger building. Major iconographic programs were produced by monumental stucco artists at sites like El Mirador, which has some of the largest ancient buildings ever built in the Americas. We were also able to piece together a much more complete look at the arc of Preclassic Maya civilization on its own terms, not as a precursor to the Classic Period.

We were able to see that major constructions began before 500 BCE, they were then taken to great heights in the Late Preclassic period after about 300 BCE, and there were a variety of factors that led to the abandonment of many Preclassic sites after about 200 CE. More paleoenvironmental studies have allowed us to see sustained droughts and anthropogenic erosion in the archaeological record to better assess the effects that humans had on a fragile rainforest ecosystem back in the day.

JBW: In what ways can we describe the material and artistic culture of the Preclassic Maya? What does Preclassic Maya art tell us about their culture and way of life?

JD: Preclassic Maya centers tend to be major investments in open spaces. They liked rectangular plazas that were paved with thick layers of smooth white limestone stucco, similar to the feeling of the bottom of a pool. Their buildings tend to be massive, rather than delicately engineered, also covered in stucco with a variety of different staircases and monumental stucco modeling. We do not really see standing monuments, so these stucco programs and the mural painting were the primary means of architectural expression, though we have to imagine they would have probably done amazing things with wood that have completely rotted away.

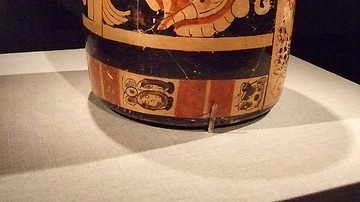

For handheld or portable material culture, we have a variety of stone tools, greenstone votive objects like the axes described above, obsidian cores and blades, marine and freshwater shell, among others. The primary mode of expression that survives is ceramic art, both in vessels and figurines. The figurines are anthropomorphic and zoomorphic and seem to be much more popular in the Middle Preclassic than the Late Preclassic, for reasons that are unclear.

Ceramic vessels are generally monochrome or bichrome, with the Late Preclassic ceramic artists innovating techniques in resist surface treatments and expert three-dimensional modeling of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms. The color world of the Preclassic Maya includes deep orange-red, grayish-black, and even cream-colored into the brown spectrum, all created by painting on slips before firing. The simplicity of Preclassic ceramics is beautiful, but another reason that the period did not receive as much public attention is that they do not include the more well-known polychrome scenes with hieroglyphic texts that the Classic ceramics have.

The available imagery from mural paintings and other artwork suggests to us that the Preclassic Maya had a sophisticated mythological world populated by deities and personified natural forces, such as animate mountains, birds of prey, and gods of lightning and maize. The mythology of maize farming was certainly influenced by earlier Olmec thought, and the Preclassic maize god visible in the San Bartolo murals shares many traits with Olmec deity depictions.

JBW: Could you tell us a bit about the end or collapse of the Preclassic Maya? Is it not just as mysterious as the collapse of the Classic Maya around c. 800 CE?

JD: I usually use scare quotes for “collapse” because at least for the Preclassic version we do not really understand the scope of what happened. For the Classic “collapse,” which generally refers to the cessation of the city-state political system based at royal courts ruled by self-proclaimed divine kings, we can measure better when people stopped living in the Southern Maya Lowlands, stopped writing on monuments, etc. But it is important to emphasize that in both cases, what we are really talking about is migration. Migration in the past is very difficult to measure, and it is clear that only some of the major Preclassic Maya sites were abandoned in the first centuries CE. Others, like Tikal, Calakmul, and many others, were continuously occupied. Some centers, such as Lamanai in Belize, were continuously occupied from the Preclassic period into the Spanish colonial period!

But the Preclassic migration seems to have been motivated by a variety of factors, just like its Classic counterpart. Environmental evidence shows a general drying, so this would have had a profound effect on places that relied on groundwater if it were drying. In conjunction with drying, increased human activity led to erosion and the buildup of sediment in water sources. We also see that many Preclassic centers that were abandoned at the time, like El Palmar, Guatemala, where I did most of my research, may have been politically vulnerable.

I have written extensively about this in Architecture and the Origins of Preclassic Maya Politics, and I argue that El Palmar and others like it were founded in open, indefensible locations, and later Early Classic settlements in the area tend to be on escarpments or other places that allowed for more surveillance of the landscape. Considering the proximity of El Palmar to Tikal, which clearly became a very powerful dynasty by the Late Preclassic, it is possible that competing claims to the landscape also led to certain populations leaving their homeland at this time.

JBW: James, I am curious to know how we ought to characterize the legacy of the Preclassic Maya within the wider Mesoamerican region? What is this era's indelible legacy to the Maya living today and other indigenous peoples in Central America?

JD: I like to think that the Preclassic Maya were incredibly gifted, being the first people to build substantial, sustainable settlements in the Maya Lowlands. Keep in mind that even though we are just scratching the surface of Preclassic civilization, this is a cultural tradition that endured for more than 1,200 years! They were active in the exchange networks that connected cultures throughout Mesoamerica. They developed farming techniques that included maize, beans, squash, and other tropical crops. They innovated techniques of architecture that would endure well into the Classic Period. They developed beautiful traditions of plastic arts and painting that heavily influenced later Classic artists. Ultimately, the Maya of today and the broader public can appreciate Preclassic Maya civilizations as one of the great global case studies in successful, thriving societies.

JBW: Finally, what advice do you have for aspiring Mesoamericanists and future anthropologists interested in the Americas?

JD: Please study art and archaeology in the ancient Americas! There are dozens of very exciting cultures that have invaluable information waiting to be discovered all across modern North, Central, and South America. There are fantastic archaeology programs in most of these countries, and we have great colleagues in Latin America doing very exciting research. My own research highly benefited and still does from deep and sustained collaboration with scholars in the countries where the Maya and other civilizations flourished in the past. The study of ancient civilizations builds our knowledge of how peoples navigated unpredictable worlds, and it can inform us of how we can improve our society today.

JBW: James, I thank you so much for your time and consideration.

Dr. James Doyle is the Assistant Curator for Art of the Ancient Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He is the author of numerous articles about ancient American art and archaeology and has formed part of the curatorial team of major exhibitions such as Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, and Fiery Pool: The Maya and the Mythic Sea. His book on the Preclassic Maya, Architecture and the Origins of Preclassic Maya Politics, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2017. James received his M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Brown University.