Daily life in the Byzantine Empire, like almost everywhere else before or since, largely depended on one's birth and the social circumstances of one's parents. There were some opportunities for advancement based on education, the accumulation of wealth, and gaining favour from a more powerful sponsor or mentor. Work, in order to produce or buy food, was most people's preoccupation, but there were many possibilities for entertainment ranging from shopping at fairs held at religious festivals to chariot races and acrobat performances in the public arenas most towns provided for their inhabitants.

Birth

As in most other ancient cultures, the family one was born into in Byzantium greatly determined one's social status and profession in adult life. There were two broad groups of citizens: the honestiores (the “privileged”) and the humiliores (the “humble”), that is, the rich, privileged, and titled as opposed to everyone else. Legal punishments were more lenient for the honestiores, in most cases being composed of fines rather than corporal punishment. Flogging and mutilation, most commonly having one's nose cut off, were common forms of punishment for such crimes as adultery and the rape of a nun. For crimes such as murder and treason, no social distinction was made with the death penalty for all. Below the two broad groups mentioned above were the slaves who were acquired in markets and through warfare.

Family names became increasingly descriptive of a person's profession or geographical location, for example, Paphlagonitis for people from Paphlagonia or Keroularios the “candle-maker”. Life expectancy was low by modern standards, anyone who got past 40 years of age was doing better than average. Wars occurred roughly once every generation while diseases were rife and ever-present. The primitive medicine was often as dangerous as the illness it sought to cure, too.

Childhood & Education

Lower class children essentially learned the profession of their parents. Aristocratic girls learnt to spin, weave, and to read and write. Perhaps they also studied the Bible and lives of saints, but they had no formal education as they were expected to marry and then look after the children, household property, and manage the slaves.

For aristocratic boys, most cities had a school run by the local bishop, but there were also private tutors for those who could afford them. Boys were first taught to read and write in Greek and then schooled in the seven classical arts of antiquity: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, harmonics, and astronomy. Such texts as Homer's Iliad and Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days were standard subjects of study and students could memorise whole chunks of them (although to what purpose is not clear other than to impress future dinner guests with weaker memories).

Higher education was available in major cities like Constantinople, Alexandria, Athens, and Gaza. The curriculum consisted of the study of philosophy, especially the works of Plato and Aristotle, as well as Christian theology. Children might also be sent for training in either the church or imperial court in the hope of social advancement. Indeed, Constantinople had a specialist school to train young men for the state bureaucracy while there was a famous law school in Berytus. In the 9th century CE, a university was created at the Great Palace of Constantinople where such academic luminaries as Leo the Mathematician taught, and then, in the mid-11th century CE, a new school of law and philosophy was founded at the capital headed by the Patriarch John Xiphilinos (r. 1064-1075 CE).

Marriage & Family

The earliest a girl married was around the age of 12 while for boys it was 14. The involvement and consent of the parents were expected and, consequently, a betrothal was usually regarded as binding. Remarriage was possible as long as a suitable period of mourning was observed by the widow, but a third marriage was rare and only permitted under special circumstances which included being without children. Divorce was difficult to achieve, although if a wife committed adultery she could be put aside and a husband left if he was guilty of murder or witchcraft. The laws of Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) went even further and prohibited divorce altogether except if both parties consented to retire to a monastic life. The father was the head of the family but a widow could inherit her husband's property and so take over that role if necessary.

Food & Drink

Mealtimes were an important family occasion, of course, and food available to the lower classes and farmers included boiled vegetables, cereals, coarse bread, eggs, cheese, and fruit. Meat and fish would have been a rarity reserved for special occasions. Richer families could afford such meat as wild birds, hares, pork, and lamb more often. Olive oil was a common condiment, many spices came from the east, and wine was widely available. Some known desserts are vine leaves or pastry stuffed with currants, nuts, cinnamon, and honey. People mostly ate with their fingers or perhaps a knife, but the two-pronged fork, used by the ancient Romans and then forgotten, did make a comeback amongst the aristocracy of Byzantium.

Jobs & Work

At the top of the Byzantine career ladder were the 'white-collar' workers who had acquired specific knowledge through education such as lawyers, accountants, scribes, minor officials and diplomats, all of whom were essential to the efficient running of the state. Then there were traders, merchants, and even bankers who might have been extremely rich, but they were held in low esteem by the aristocracy and viewed with some suspicion. Craftsmen and food producers (men and women) were less socially mobile as members of the major guilds (collegia) were expected to remain in their professions and pass on their skills to their children. This was especially so for vintners, ship-owners, bakers, and pork producers. Women did many jobs that men did but often provided specialised services as midwives, medical practitioners, washerwomen, cooks, matchmakers, actresses and, of course, as prostitutes. Women could own their own businesses if they had the means.

Although converting ancient currency to modern ones can be misleading, it is interesting to compare the value of one profession's work with another as seen in these values mentioned in Diocletian's monetary reforms of the early 4th century CE, which give an idea of labour costs in the early Byzantine Empire:

- 25 denarii for one day's wages for a labourer

- 50 denarii for one day's wages for a baker

- 150 denarii for one day's wages for a painter.

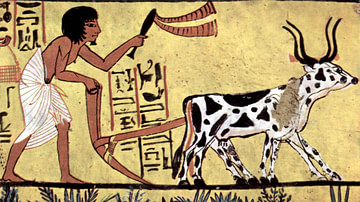

The largest population group was the small-scale farmers who owned their own land and the most humble citizens of all who worked as agricultural labourers (coloni) on the large estates of the aristocratic landowners (dynatoi). This labourers were not very much higher or treated better than slaves who were the lowest of the low.

Housing

The well-off had large multi-roomed houses with inner courtyards, bathrooms, gardens, fountains, and even a small chapel. The public rooms of such houses had marble floors and walls decorated with mosaics while those private rooms such as bedrooms, which were usually on the second floor, had painted interiors. Grander houses even had a segregated part of the home reserved only for the women of the household, the gynaikonitis, but this seems to have been a private space to keep men out rather than a restricted place from which women could not leave.

Most ordinary folks' houses were built using bricks and stones, often from older damaged buildings. To give a smarter appearance, exterior walls were covered in plaster and often incised with regular lines to make them look like they were made from regular stone blocks. Even more common was to paint the walls in bright colours, sometimes with bold geometric patterns. These types of homes had only rudimentary sanitation, and we know that laws forbade city residents from emptying their chamber pots out of the window and into the street.

Many poorer citizens would have lived in the simple multistorey buildings the western Romans had created, the insulae. Still more lived on the outskirts of town in ramshackle buildings of wood, mud bricks, and reused rubble. In rural areas, a small group of houses might be built to form a village. Buildings here had two stories - the lower for animals and the upper for the farmers - and an inner courtyard overlooked by a verandah. Rural houses had no running water, and there is no evidence of interior bathrooms. Perhaps surprisingly, these country houses were often built of dressed stone with well-carved frames and niches.

There were no planning rules, and the various designs and materials used in buildings meant that the towns presented an eclectic urban landscape with a maze of small haphazard streets. Outside the town or city were such communal places as those for washing clothes, the rubbish dump, and an execution ground.

Clothing

The aristocracy wore fine clothes, including silk, which was first imported from China and Phoenicia and then produced in Constantinople from 568 CE. Nobles could wear clothes dyed with Tyrian purple, which set them apart from commoners because it was tremendously expensive to produce and they were banned from wearing it anyway. The rich Byzantines also liked a bit of gold, silver, and gemstone-studded jewellery, too. Aristocrats were not entirely free from fashion rules, though, as Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) decreed that nobody except himself could embellish their belt or their horse's bridle and saddle with pearls, emeralds or hyacinths.

Certain high-ranking officials even had their own distinct clothes of office. The colour of a cloak, tunic, belt, and shoes, or the particular design and material of a fibula could indicate visually the wearer's office. Indeed, some of the buckles worn were so precious and the risk of theft so high that many officials wore imitations made from gilded bronze. Poorer members of society had to make do with less splendid attire with the woollen short tunic and long cloak dominating wardrobes, trousers not being introduced to Byzantium until the 12th century CE.

Leisure

Getting out and about in a Byzantine town was an entertainment in itself, much like any modern metropolis today, as the streets were filled with jugglers, acrobats, beggars, food and drink vendors, idlers, prostitutes, fortune tellers, lunatics, holy men ascetics and preachers. Citizens could shop in markets which were held in dedicated squares or in the rows of permanent shops which lined the streets of larger towns and cities. Shoppers were protected from the sun and rain in such streets by collonaded roofed walkways, which were often paved with marble slabs and mosaics. Some shopping streets were pedestrianised and blocked to wheeled traffic by large steps at either end.

Goods in markets were scrupulously weighed out using official standardised weights and measures. Prices, too, were regularly checked by state inspectors to ensure there was no unnecessary profiteering. Especially good moments to go shopping were during the many festivals and fairs held on such important religious dates as saint's birthdays or death anniversaries. Then churches, especially those with holy relics to attract pilgrim visitors from far and wide, became the centrepiece of temporary markets where stalls sold all manner of goods. One of the largest such fairs was at Ephesus, held on the anniversary of Saint John's death.

In smaller towns, the theatre served a similar purpose, as well as being a place of public meetings which not infrequently developed into a riot that spread through the town in protest of local government policies or high taxes. Another sporting venue was the stadium where athletic contests were staged. Finally, there were plenty of places where both men and women could just hang around, meet up and chat over the issues of the day such as the public baths, the local gymnasia or even church.

Death

The dead were commonly buried in dedicated cemeteries located outside the town proper. Different classes ranging from public officials to actresses had epitaphs carved in stone above their graves and illustrate that commemorating the dead was not a practice limited to the rich. Further, these epitaphs are a valuable source of information regarding Byzantine daily life, revealing such details as names, professions and attitudes to life in general.