Thanks to their favoured position in life and the labour of the peasants on their estates, nobles in an English medieval castle had plenty of leisure hours which could be frittered away by eating, drinking, dancing, playing games like chess, or reading romantic stories of derring-do. Other ways to pass the time and impress one's peers were hunting in the local forest or deer park, falconry, jousting, needlework, composing poetry, playing music, and watching professional acrobats, jugglers, and jesters.

Hunting

Many larger castles would have had their own stables, so horse riding was a possible form of leisure but riding for a purpose was perhaps even more popular. Hunting was the greatest example, and it was not only a leisure pursuit but had the practical rewards of improving horsemanship and dexterity with weapons, as well as livening up the castle dinner menu, too. A professional huntsman and his beaters and dog handlers stalked the animals in the local forest or protected deer park using leashed dogs. When ready a horn was blown to signal the off, and then the nobles - both men and women - rode with a pack of hunting dogs to chase down animals such as deer, boars, wolves, foxes, and hares. The breed of dogs commonly used were the hound (brachet), greyhound (levrier), and bloodhound (lymer). For the more formidable boar, the breed used was the alaunt, which was similar to the modern German shepherd.

The whole hunting party included retainers and grooms, and so there was the possibility of a picnic mid-hunt. Once an animal was cornered a noble was given the opportunity to make the kill using a lance or bow and arrow. Even if a lord did not have his own hunting grounds, he could always pay for the privilege elsewhere as many large estate owners offered the right to hunt on their grounds for an appropriate fee. Forests were a hugely valuable resource in medieval times, and they had their own officers and inspectors to make sure they were not damaged by local farmers. Deer parks, ranging anywhere from 400 to 4000 square metres, were enclosed by earthworks, fences, and an encircling ditch. Infringements such as grazing livestock or felling timber on a castle's lands without permission led to prosecution in courts dedicated to forestry matters. Anyone who was caught poaching met with severe punishments such as fines, imprisonment, or even blinding. Finally, a fine hunting park next to one's castle was a powerful social statement in the competitive environment of aristocratic one-upmanship. Size, number of animals, and scenic additions such as ponds, as well as the granting of gift licenses to hunt in them, were all ways for a castle owner to impress friends and visitors alike.

Falconry

The use of birds to kill other birds is an ancient practice and, in the medieval period, falconry was especially popular across Europe. Just about any self-respecting lord had his own falcons, and his favourite bird very often shared the lord's bedroom at night and was rarely off his master's wrist during the day. Without firearms, a falcon was the only way to catch birds which flew beyond the range of an archer, although for the medieval nobility, the whole sport had a mystique and mythology about it beyond the expedience of bagging a few fowl for the table. Indeed, women also practised falconry, as can be seen on many seals depicting a noblewoman holding her favourite hawk. Such was the importance of falconry that there were books written on how to excel at it, most famously The Art of Falconry (De Arte Venandi cum Avibus) compiled by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250 CE). Popular birds of choice were the gerfalcon, peregrine, goshawk, and sparrowhawk, amongst others. The birds were expensive to train and keep, so the more a lord had in his castle mews, the better he could impress his friends. Both waterfowl and forest birds were targeted, especially cranes and ducks.

Tournaments

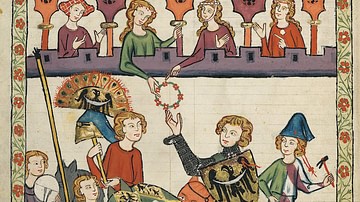

Like hunting, tournaments gave knights the chance to hone their skills with horses and weapons in a relatively safe and controlled environment, although there could be injuries and fatalities despite the precautions. The competitions took two formats, either a mêlée, which was a mock cavalry battle where knights had to capture each other for a ransom or the joust where a single rider armed with a lance charged at an opponent who was similarly armed. To minimise the risk of injury, weapons were adapted such as the fitting of a three-pointed head to the lance in order to reduce the impact and swords were blunted (rebated). Such weapons became known as 'arms of courtesy' or à plaisance. The popular Round Table tournaments involved knights dressing up as characters from the legends of King Arthur who then jousted and feasted in costume. Watched by an audience which included the local aristocratic ladies, motivation to perform and display chivalry was high. There were also prizes such as a gold crown, jewels, or a prized hawk so that many knights made a living doing a tour of tournament events across Europe.

Even if a local tournament was not perhaps a regular event, one could at least practice for them. A common device to hone one's lancing skills was the quintain - a rotating arm with a shield at one end and a weight at the other. A knight had to hit the shield and keep riding on to avoid being hit in the back by the weight as it swung around. Another device was a suspended ring which the knight had to catch and remove with the tip of his lance.

Literature

As part of the code of medieval chivalry, gentlemen were expected not only to be familiar with poetry but also capable of composing and performing it. Books, really sheaves of illuminated manuscripts, were available on all manner of subjects besides poetry, though. There were handbooks for self-improvement such as good etiquette at table and chivalry in general, none more famous than the c. 1265 CE Book of the Order of Chivalry by Raymond Lull of Majorca. There were treatises on such quintessential aristocratic pursuits as hunting and falconry, as mentioned above.

Then there were the stories which had survived from antiquity such as the Trojan War or adventures of Alexander the Great where characters and events were given a distinctly knightly, chivalric slant appropriate to the medieval mind. Perhaps the first work of this genre was Benoit de Saint-Maure's The Romance of Troy (c. 1160 CE). The legend of King Arthur was further popularised by such authors as the 12th-century CE Englishman Geoffrey of Monmouth and Frenchman Chrétien de Troyes. The tale of Saint George's tussle with a dragon was popularised by the c. 1260 CE The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine. There even sprang up romances and romanticised biographies of famous medieval knights like Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) and Sir William Marshal (c. 1146-1219 CE).

Although aristocratic women might do a little embroidery and spinning to fill the hours, they had often been educated and so could read, write, and perform poetry. Castle architecture reflected these leisure pursuits by incorporating into their inner-facing walls windows with their own seats in order to provide a place with good lighting. Noble ladies might also be sponsors of poets, some forming celebrated literary circles.

Board & Parlour Games

If the weather was not conducive to a game of bowls on the castle lawn, then indoor games might be the order of the day. Backgammon, dice, and chess were all popular games in the medieval period with both men and women. These games might involve a bit of betting to make them more interesting. Gambling does not seem to have suffered from any negative reputation, and even clergymen are recorded as indulging in it. Chess, introduced to Europe from India via Arabia c. 1000 CE, was known as 'the royal game' because of its huge popularity. There were two varieties - one very similar to the modern game and another, simplified version which involved dice. Knights even played chess when on campaign to while away the more tedious moments of long sieges, as depicted in medieval manuscript illustrations.

Parlour games included hot cockles, where one person must kneel while blindfolded and guess the identity of the person striking him. Another game was hoodman blind where one person must catch another member of the group but have his head covered by a hood.

Children had toys to play with when they were not studying under the local chaplain or one of his clerks. These included dolls, balls, spinning tops, and toy weapons such as bows and arrows. Archery, in particular, was a popular pastime for aristocratic boys. One can also imagine that wooden swords were used as playthings to ready a boy for his later fencing classes, a popular sport with aristocratic men.

Music, Dance & Festivals

Eating was, of course, often an entertainment in itself, and in a castle, the main meal was an early lunch which might run to ten courses. After the meal, guests might dance, one type being the carole, where everyone held hands, danced in a circle, and sang. Guests were often amused by professional entertainers such as jugglers, and harpists, especially during a dinner. Troubadours (aka trouvères, travelling artists) and minstrels (in the employ of a castle) were particularly popular as they sang and played the lute, recorder, shawm (an early version of the oboe), vielle (an early violin), and percussion instruments such as drums and bells. They performed chanson de gestes and chansons d'amour, epic poems in Old French which told familiar stories of knightly daring deeds and impossible romances respectively. Other types of songs included laments, spinning songs, and political satires (sirventes). As noted above, many gentlemen took a turn at singing a song or performing a poem to music at a castle dinner party. A jester (ioculator) might tell jokes while making amusing sound effects with a bladder-slapstick or actors (ystriones) might perform serious dramatic scenes.

Naturally, holidays and festivals offered the opportunity for even more lavish meals and festivities. Then, as now, there were many Christian festivals and feasts but Christmas was the highlight of the year. With a 14-day holiday from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day (6th January) the norm, the castle was decorated with holly, ivy, and bay. A huge Yule log was put in the Great Hall's fireplace and kept alight for the duration of the holiday. Knights in service of the local lord were given fine robes or even jewels as gifts. At this time of year, groups of pantomime artists known as mummers wore masks and went around houses performing and playing dice, receiving food and drink from their hosts in return.

Even the castle's staff and farmers had reason to celebrate, receiving their Christmas bonus in the form of food, drink, clothing, and firewood. The local tenants might also receive a Christmas dinner in the castle, albeit using food they had themselves provided for the occasion (they even brought their own dishes, napkins, and firewood). They could take away any leftovers and there was a game known simply as the “ancient Christmas game” where the lucky finder of a bean buried in one of the bread loaves could act as the king of the feast.